BERNADETTE McALISKEY is a veteran civil rights campaigner and remains the youngest woman ever elected to parliament. In a comment article written for The Legacy series she argues that agreeing a Bill of Rights for Northern Ireland should have been the bedrock on which we moved forward from conflict to peace.

THE inevitable failure of the Hass talks, and the unravelling and entanglement of the web of deceit which necessitated them owes much to the absence of a Bill of Rights as the cornerstone of ‘the new dispensation’ for N. Ireland whatever that actually means, and to the absence within the political process at Stormont of a second tier of public representation, not dependent for its existence on managing the interface of segregation politics.

These two aspects of the Belfast Agreement – the Bill of Rights and the civic forum – have effectively been binned as there is no intention or willingness on any part of the main political parties to implement either and open hostility within each of the party leaderships to both.

The lack of political party appetite for either is interesting in the context of one politician or another supporting competing demands for all kinds of rights to be upheld including newly invented ‘rights’ which appear like rabbits at the drop of a hat, flag, commemorative parade or funding opportunity.

The equally frequent assertions of communal disengagement from the political process from politicians and communities on either side of the sectarian argument, to say nothing of the growing diversity of interests asserting that nobody speaks for them is intellectually at odds with the collective fear and derision with which the concept of a wider civic participation in the political process beyond passive voting.

It is not my intention to analyse the rationale for this paradox, as we are treated once again to the Alice in Wonderland logic by which failure means success because that is what you want it to mean. Of greater importance is the impact on the developing peace process of the absence of these essential pillars of peace-building.

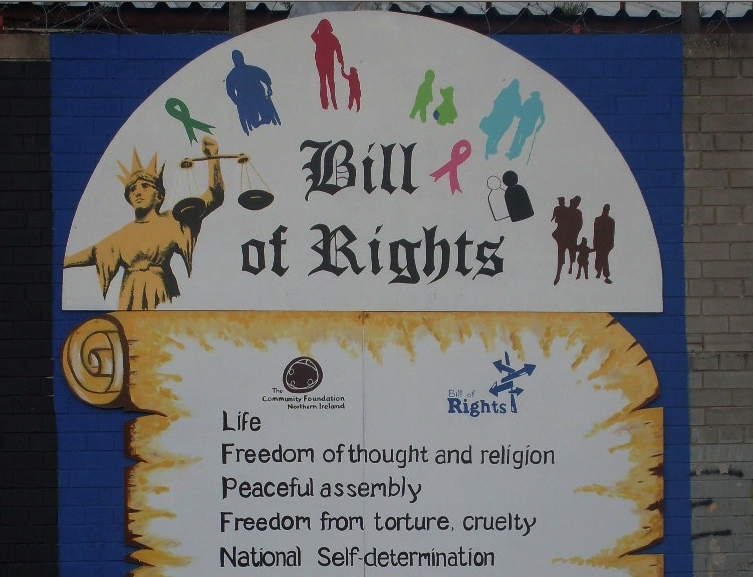

Agreeing a Bill of Rights for Northern Ireland should have been the bedrock on which we moved forward from conflict to peace.

The engagement of the civic population in an honest, open and learning process of discussion and debate and shared learning about the universal concept of rights; rights holders and duty bearers and the social and civic responsibility of all of us to protect and defend the rights of others as vigorously, and tenaciously as we assert and defend our own would have taken us to a different place than we currently are, which is, in my opinion, why it was never allowed to happen. Such a discussion is currently energising the Scottish debate on independence.

It was not that nobody argued for it, the argument was lost, not least because those tasked, paid and resourced to lead it failed to exercise any leadership in the matter and allowed that core discussion to become secondary to the demands of the Trojan horse traders.

That is not to argue that a Bill of Rights in and of itself solved the problems that had to be resolved. What it would have done was provide a framework capable of bearing the weight the problems to be resolved.

It would also have widened the discussion beyond the competing interests of ‘Orange and Green’ to a conversation based on an understanding, not common in these parts, that the theory is based on the acceptance that every single human being has exactly the same fundamental human rights.

Throughout history, some individuals and groups of people have those rights routinely denied and violated because those with the power and duty to protect them fail to do so, at best, and actively violate them, at worst.

Throughout the whole world, it boils down to abuse and inequality of power; the institutionalising of privilege and prejudice at key levels of society; the absence of an effective democratic process for redressing these issues.

The inevitable outcome is conflict, violence and war. There is nothing unique to Northern Ireland about this inevitability. What is unique, as in every unique location is the specific context in which it all plays out.

In 1992 Boutrous Boutros-Ghali set out the ‘An Agenda for Peace’ when he became Secretary General of the United Nations.

Almost incredibly, this was the first formal recognition at UN level of the concept of post-conflict peace-building, defined as “action to identify and support structures which will tend to strengthen and solidify peace in order to avoid a relapse into conflict.”

That UN concept underpins the European approach to the conflict here and informed the setting up the European Union Structural Peace Funds. It also underpinned the principles of the South Tyrone Empowerment Programme (STEP) co-founded by Anne McGlone, myself and others who despaired of the lack of integrity of the American led- ‘political’ process which reduced all human life to the ‘two traditions’

Integrating structures for the understanding, protection of human rights and access to local remedy resolving human rights disputes are at the heart of peace-building as is equal access to power, democracy, social and economic resources and opportunity.

The organic development, from the outset, of a Bill of Rights in N. Ireland that embraced economic, social and educational inequality might have got a better hearing in a civic forum than in the then emerging party political carve-up on the hill. Hence its demise from a stillborn start, as Mr Larkin might describe it.

Without these integral parts of the peace-building process, we have, by default, had for the past fifteen years no more than a non-militarised peace-keeping process, which is running out of time while the Minister of First Nero and the Deputy Minister of the First Nero preside over the Titanic orchestra and play ‘The funds of Europe’.

Maybe we should invite Boutros Boutros-Ghali to chair the next round of talks.