Deputy director of the Committee on the Administration of Justice (CAJ) Daniel Holder explains citizens' rights post Brexit.

Discussion on Brexit and Northern Ireland has focused extensively on the potential hardening of the land border, or a border in the Irish Sea. However, beyond that are numerous questions as to the impact of Brexit on the entitlement-boundaries between different groups of people born or living in Northern Ireland depending on their citizenship status.

As is known in Northern Ireland citizenship is, in part, an expression of national identity. It is also about the relationship between a citizen and State and their rights and entitlements when they interface with public authorities.

This is complex as many rights and entitlements are not dependent on citizenship. Human rights (e.g. fair trial) as the name suggests, are usually not citizens’ rights. Some entitlements are based on residency. (E.g. full NHS medical care is generally based upon lawful ‘ordinary residence’ not nationality). In recent times entitlements to work, many public services and social security have increasingly been restricted by citizenship and related immigration status.

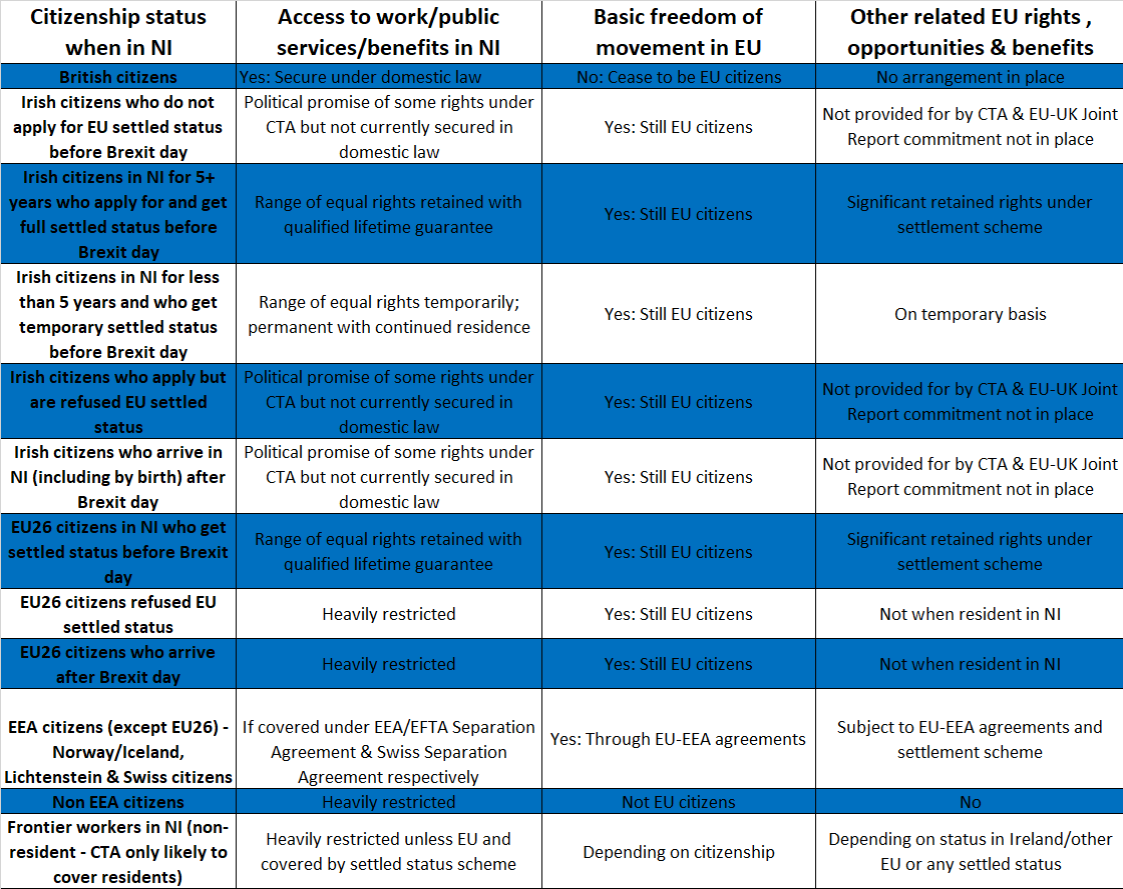

The graphic below covers three key areas of entitlements:

- Rights to reside, work and access services and benefits when in Northern Ireland.

- Basic freedom of movement in the EU.

- Subsidiary EU rights, such as being joined by (non-EU) family members, qualification recognition or access to health care in other EU states.

As things stand there are generally two citizenship status categories:

- Pre-Brexit Category 1: All EU/EEA citizens – including British and Irish citizens - who have access to all three sets of entitlements.

- Pre-Brexit Category 2: Non-EEA citizens – who don’t have EU rights and are heavily restricted in access to work and services/benefits in NI.

The implications of the draft Withdrawal Agreement, and any other Brexit that does not permit continued freedom of movement into NI, is that it places every group at some form of disadvantage.

Boundaries between citizens' rights after Brexit

- Brexit day: end of Brexit transition period (planned for December 2020);CTA - Common Travel Area (UK-Ireland and Channel Islands/Isle of Man; EU settled status scheme - provided for under Part II of Withdrawal Agreement)

Problem 1: Discrimination and denial of rights

Whilst the current two categories may seem straightforward, their enforcement and the denial of rights have been particularly draconian in recent years under the ‘Hostile Environment’ policies introduced by Theresa May as Home Secretary.

This subcontracted the policing of immigration to public services and the private sector including banks, landlords and educational institutions. The impact of this is (but not restricted to) the ‘Windrush’ scandal.

With over a dozen new categories of differentiated rights-holders it is predictable that racial profiling (the form of discrimination whereby persons are singled out for greater scrutiny on the basis of skin colour or other ethnic attributes) will become even more widespread. Even when restrictions are correctly applied, some are so draconian as to deny basic human rights to people who are, for example, homeless, or victims of domestic abuse. Actual or perceived non-EEA nationals currently bear the brunt of this, but the expanded scope will cover many more people.

Problem 2: Compliance with the Good Friday Agreement

Enshrined in the Good Friday Agreement (GFA) Treaty the British and Irish governments recognised the birthright of the ‘people of Northern Ireland’ “to identify themselves and be accepted as Irish or British, or both, as they may so choose”.

When read with the equality and parity of esteem provisions of the GFA this is not merely a provision that allows persons to choose a British or Irish passport (or both). Rather the provisions ensure equal treatment between British and Irish citizens as a result of their choice. This is set out clearly in the UK’s Brexit policy papers.

At present, within the EU context, Irish and British citizens are in the same entitlements category. Both will experience differential treatment and different forms of disadvantage post-Brexit.

An examination of some of the categories further highlights these problems.

British citizens resident in NI

The entitlements of British citizens to work and access services in NI are secured in domestic law. EU citizenship is for citizens of a member EU state, and the basic freedom of movement is lost along with subsidiary EU rights and opportunities for British citizens on Brexit day.

Citizens of EU26 countries (i.e. EU excluding Ireland) resident in NI

All citizens of EU member states are automatically EU citizens, and regardless of where they live they retain some EU citizen rights. These are most notably freedom of movement to visit, work, study, and retire elsewhere in the EU, along with some more administrative rights, such as the right to petition the European Parliament.

However, the continued access to many EU rights, opportunities and benefits is more complex and requires specific arrangements. Practical access to and exercise of them is normally either dependent on residency in an EU member state, participation in EU programmes or social security coordination between countries. As NI will not be part of a member state, a specific arrangement is needed for EU nationals already here to retain rights to reside, work and access services.

The Withdrawal Agreement provides for an EU Settlement Scheme for EU citizens already in the UK (and British citizens elsewhere in the EU) to retain many EU rights and benefits – including access to work and services in their place of residence. The Home Office is to charge £65 per adult for applications under the scheme, which is to open in April 2019.

However, it is predictable that should this happen, many EU26 nationals will face obstacles in successfully applying to the EU Settlement Scheme, particularly those who have worked in more informal sectors of the economy. The whole purpose of the scheme is to differentiate pre-Brexit EU26 from fellow citizens who arrive after Brexit.

EU26 nationals will therefore fall into several different categories.

Irish citizens resident in NI

This is perhaps the most multifaceted and differentiated citizenship category. Given the GFA birth rights provisions it might be presumed that rights to reside, work and access services and benefits in NI are directly provided for in domestic law for those who choose to be Irish citizens. In fact, in large part this is often not the case. Irish citizens in NI only have many such entitlements either on the basis of EU law (that will be lost on Brexit) or on the basis of being treated by the UK as British, in conflict with the GFA.

In the context of Brexit, the UK Government has long promised that the “associated rights” of the (UK-Ireland) Common Travel Area (CTA) will allow all Irish citizens in NI (whether NI born or not) continued access to entitlements in six named areas - rights to 1: enter and reside; 2: work; 3: study; 4: social welfare; 5: health services; 6: to vote. The Irish government provides this reciprocally for British citizens in its jurisdiction.

There are however a number of issues accessing these CTA ‘associated rights’, not least in that they have been consistently politically promised but not currently fully provided for in domestic law. Even if fully written into domestic law, the absence of enshrinement in a treaty or Bill of Rights means CTA rights could be changed by any incoming government.

There is also no clarity as to the scope of what CTA rights will actually cover. Does ‘study’ cover schools as well as third level education? What range of benefits does it cover – e.g. social housing? Voting is restricted to local and parliamentary elections – and not paradoxically referendums (which would include a border poll under the terms of the GFA).

CTA rights by definition will not cover any entitlements outside the CTA itself – and there is no commitment to cover cross border provision (e.g. schooling or health care) or recognition of qualifications.

If this persists it is likely to make an application for Irish citizens under the EU settlement scheme a more attractive option (save the cost). This would ensure the retention of a range of EU rights largely guaranteed for life. This will not be open to any Irish citizen who ‘arrives in NI’ (which includes being born) after Brexit Day, and anyone in NI less than five years will have to stay for five years to get permanent residence status.

The relationship with EU broader rights, opportunities and benefits is not straightforward either. The December 2017 ‘Phase 1’ EU-UK Joint Report committed to arrangements for the maintenance of a broad range of EU based entitlements for Irish citizens. However, the commitment was politically promised but no such arrangements were put into the Withdrawal Agreement.

Retaining some EU rights will be possible under the EU Settlement Scheme. The official line has generally been that Irish citizens can but ‘need not apply’ under the scheme (due to the CTA).

However, the Home Office may also seek to refuse applications from NI-born Irish citizens. The issue arises as the Home Office has taken an interpretation of the GFA, despite its clear wording, that the birthright only extends to persons ‘identifying’ rather than being ‘accepted as’ Irish. Whilst inconsistent, the Home Office has therefore treated NI-born persons as ‘British’ for administrative purposes regardless of their GFA choice, most often precisely when seeking to access EU rights. This would render NI-born among the only EU citizens in the UK not able to retain EU rights, and further subdivide already complex categories.

Others

EEA nationals who are not EU26 are subject to separate agreements. The situation of non-EEA nationals does not improve. Then there are the circumstances of persons in NI but not residing here – most notably cross border workers, who are in separate categories.

Persons can also fall into more than one category and many of the above categories could also themselves be subdivided further.

As if decision making by the Home Office was not already poor enough the ‘hostile environment’ framework hands decision making powers on entitlements to a broad range of largely unqualified persons.

The complexity of the range of differentiated categories envisaged post-Brexit is largely a product of the thrust of the main Brexit campaign revolving around ‘taking back control of borders’.

Politically this ensured the ‘soft Brexit’ option of continued free movement was taken off the table. The result is the requirement of what will be a costly and complex system to differentiate different types of citizenship status to ensure that those deemed ‘not entitled’ (a fraction of 1% of the population) are excluded.

Daniel Holder has been the deputy director of the human rights NGO the Committee on the Administration of Justice (CAJ) since 2011. He is also the co-convener of the Equality Coalition – a network of equality NGOs and trade unions jointly convened by CAJ and Unison. He is a member of the BrexitLawNI team, a partnership between the law schools of Queen's and Ulster Universities and CAJ focusing on the constitutional, peace process and human rights implications of Brexit.