WHY would a £2.5million state-of-the-art residential home for people with dementia be only one-fifth full four months on – when the need for dementia care is greater than ever?

The case of Gnangara home in Enniskillen, Co Fermanagh, illustrates the tough choices which have to be made in looking after our vulnerable elderly population. It opened at the end of last year but only six of its 30 places have been taken up – yet there are 650 people in Fermanagh who are known to have dementia.

Dementia and general care for the elderly is one of the biggest public health issues facing Northern Ireland. It has implications for the public purse and profound implications for the way we all live – and especially the extent to which relatives of patients shoulder the burden of care, both in terms of looking after their loved ones and in terms of paying for it.

At the moment around a quarter of the £230million-a-year of public funds spent on dementia goes towards informal care costs. The rest is divided up between private residential and nursing homes, hospitals and other health institutions.

Thousands of individuals and their families are topping up the public bill from their own pockets and from the sales of assets including family homes, yet no figures for this are recorded in the dementia consultation.

It’s clear that resourcing this growing burden in the future will be an enormous issue for Government and the people who vote for them – and that health policy is leaning towards keeping dementia sufferers in the community rather than residential homes.

We approached a representative from Gnangara for an interview but they declined to comment. However, in a statement to The Detail the Western Health Trust, which jointly commissioned the development, admitted the project would take time to reach its full potential.

They said: “Since the registration of the scheme in late December 2010, the Trust has been working with Fold to identify clients whose needs can be appropriately met within this new facility. This process involves discussion with clients and families in relation to their preferred choice of facility and to ensure that they are aware of the full range of options available.

“When new facilities such as Gnangara are commissioned, it is the experience of the Trust that it takes a period of time for the places available to be filled by those assessed as requiring such placements. The Trust continues to work with Fold and all providers to make optimum use of the services and facilities available to meet the needs of the local population.”

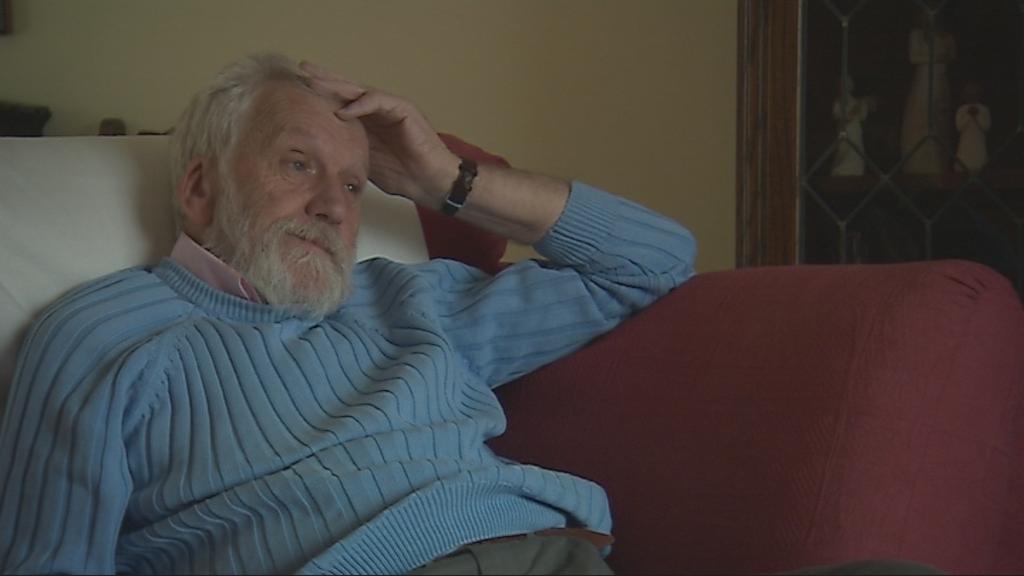

When Gayle McKee’s father was diagnosed with dementia six years ago she made the decision to move back to Northern Ireland and accepted a job offer in Holywood.

Her father had been living on his own in Fermanagh, but as the symptoms progressed the family decided it was no longer safe for him to be living alone so far away and went about looking for suitable accommodation for him close to Gayle and her son Joshua.

Gayle said: “That was very difficult because he kept saying, ‘You know where am I going?’ and all I could say was, ‘Dad I don’t know I can’t tell you’. But we were very fortunate in the long run and a place became available in Holywood, but it really was a gamble. With the nature of the disease any change in circumstances can cause rapid deterioration.”

The one comfort for Gayle was that her father had savings, which meant financially there were options and they were able to afford sheltered housing for him close by.

She said: “I feel sorry for people who don’t necessarily have this, because even though I had choices, it scared the living daylights out of me.

“People with dementia are still people at the end of the day and deserve to have this support available.

“My father still has a role to play, he still plays with his grandson, my son and enjoys spending time with him. He can still do things and just because he has dementia doesn’t mean that he doesn’t have a role to play in society.”

Whether it’s for financial or personal reasons, placing a loved one in specialist housing or a care unit isn’t always the ideal option.

Throughout Northern Ireland people with dementia continue to live at home or within their family’s home and this is only possible because of the support from carers- friends and relatives who look after loved ones for free.

Colum Conway, chief executive of Extra Care Northern Ireland, believes that whatever the makeup of the new Assembly it will be impossible to ignore the financial implications of providing care for the vulnerable and elderly in Northern Ireland for years to come.

He said: “All our demographics point to the fact our population is getting older, living longer and is likely it require more care into the future and yet the resources that we have available to us for social care are increasingly coming under pressure.

“We are calling for an immediate independent review on social care in Northern Ireland as one of the first acts of the new Assembly."

Statistics from Carers NI show there are approximately 185,000 carers in Northern Ireland who save the Northern Ireland economy over £3.12billion a year – more or less the equivalent of NHS annual spending here.

Mr. Conway said: “Dementia is a crucial part of this because people are living longer and the likelihood of people living longer with dementia is increasing and the potential need for care and support will increase as well. We need to find out what the provisions for the future are.”

Professor Scott Brown is chair of the Royal College of Practitioners. He believes with projections for people who have dementia in Northern Ireland continuing to grow, the system of care will not be able to cope.

He said: “It may be a quiet problem but it’s growing, it won’t go away and I think any humane society, any democratic country, needs to consider these patients, their needs and the needs of their carers and how we’re realistically going to be able to financially sustain this in the years to come.

“Certainly we at the Royal College of General Practitioners will be lobbying and willing to sit down and talk to the Health Minister, the Health Committee and anybody else about the needs of these patients and carers – if they want to listen to us.

“Carers are fundamentally important, first of all for the patient who has this disorder, the last thing they want is to meet lots of new faces, or to feel at the early stage that they are being deemed incompetent. It is well known that if you take a patient who is mildly confused into a new environment with which they are not familiar that can actually aggravate the confusion so caring for people in the environment they feel secure in when they’re at risk is the most important thing.”

Every year around 69,000 people move into a new caring role in Northern Ireland. Statistics from Carers Northern Ireland show that one quarter of all carers provide over 50 hours of care per week and that people providing high levels of care are twice as likely to be permanently sick themselves, with 61% reporting having health problems.

In November 2009 Fermanagh woman Ann Barbour, who suffered from Alzheimer’s, was found dead in her Enniskillen home. The body of her husband, Bill Barbour, was found in a lough close by.

Mr Barbour was her primary carer and after their deaths it was revealed the couple had an agreement to end their lives if Mrs Barbour’s Alzheimer’s became “too degrading”.

During the consultation period on the draft Dementia Strategy, the Alzheimer’s Society surveyed its members and service users over the summer of 2010.

Eighty-eight percent of respondents were getting some, but not enough help and support.

While the society will not comment on any specific cases, they acknowledge the role of the carer can be an isolating one.

Elizabeth Byrne from the Alzheimer’s Society said: “ Because of the gradual and progressive nature of the condition, a significant and growing level of responsibility falls to the carer; this is made more acute by the unrelenting nature of caring, when a person is living at home.

“Carers are faced with a demanding role in emotional, practical and social terms and their own health and well-being can be compromised if they don’t have sufficient support and respite.

“This can happen because a carer feels they can’t or don’t want to ask for help or because support they could do with is not known about, not available or not easily accessible to them.

“Regardless of the reason for the gap in support, its effects can compound an already difficult set of circumstances, with detrimental consequences for all concerned.”

The debate around the need for better provision for carers isn’t something that’s exclusive to Northern Ireland. The independent commission reviewing long-term care funding in England is expected to propose a cap on costs for individuals when it reports in July.

The Commission on Funding of Care and Support, chaired by Andrew Dilnot, was set up in July last year.

Ahead of the findings of the review being published later this year, Mr Dilnot revealed the commission is looking at ways the state could cap long-term care costs to help people make the necessary provision. This would involve a reduction in the amount elderly people should contribute to their social care.

Many health charities here believe whether it’s caring for someone with dementia or any other condition, Northern Ireland should follow suit in addressing all of the issues.

Colm Conway from Extra Care believes now is the time to act.

He said: “My message would be to immediately introduce an independent review of social care, along the similar lines of the Dilnot, to give us a clear picture of how we might progress and to use the resources that we have now and in the future effectively and efficiently to provide care for our elderly here.

“It really is a matter of whether we choose to honour our duty to provide care and how we provide it. The one crucial thing is that the people who need care and support will always be there and they will always need that care.”

By

By