THE Detail has launched a major new project on political divisions in Northern Ireland, which are at risk of being deepened by the UK’s decision to leave the European Union.

A specially developed interactive map reveals the extent to which Catholic and Protestant communities continue to live apart in Northern Ireland, nearly 20 years after the violence of the Troubles ended.

The map also illustrates dramatic shifts in demographics, with the decline of the Protestant community and the rapid increase of the Catholic population.

Additional analysis exposes the myths of a new unifying ‘Northern Irish’ identity between the communities, showing instead that the contest between British and Irish allegiances continues.

While there has been a focus on the economic implications of 'Brexit' - Britain’s exit from the European Union (EU) – it also represents the biggest political challenge for the island of Ireland since the talks that secured the Good Friday peace agreement of 1998.

The project, published in partnership with The Irish Times, aims to widen debate following the UK government’s decision to begin the formal process of leaving the EU.

The colour-coded map, available here, uses government data on religion from each census held in 1971, 1981, 1991, 2001 and 2011 to show where Protestants (in blue) and Catholics (in green) live in Northern Ireland.

The data avoids identifying individuals, but is of sufficient depth to illustrate the degree to which cities and towns remain divided or are predominantly populated by one community.

The shifting patterns in Belfast and Derry/Londonderry are illustrated in animations here.

Click here to see The Detail's interactive map.

Religious identity is closely linked to political identity in Northern Ireland.

Irish nationalist parties draw support mainly from the Catholic community, while unionist parties linked to the British identity draw support mainly from the Protestant community.

The 2011 census found 21% of people selected a new national identity option of 'Northern Irish', which was subsequently characterised in the media as a new centre ground.

However, analysis shows the 'Northern Irish' include many who see the label as a variation of traditional Irish or British nationalities and who vote predominantly for unionist or nationalist parties, rather than centrist parties.

Brexit has coincided with major population shifts in Northern Ireland, which already presented a challenge to the political process.

Northern Ireland was created with an in-built two-thirds Protestant majority when the island of Ireland was partitioned almost a century ago.

But the 2011 census revealed that the Protestant population had fallen to 48%, while the Catholic population was put at 45% and projected to become the majority community.

POLITICAL SHIFTS

The Good Friday agreement delivered an end to large scale violence, while also creating a power-sharing government involving unionists and nationalists, with safeguards for all communities.

It secured Northern Ireland’s position within the UK, but with the option that at some future point a majority could opt instead for Northern Ireland to join a new all-Ireland political structure.

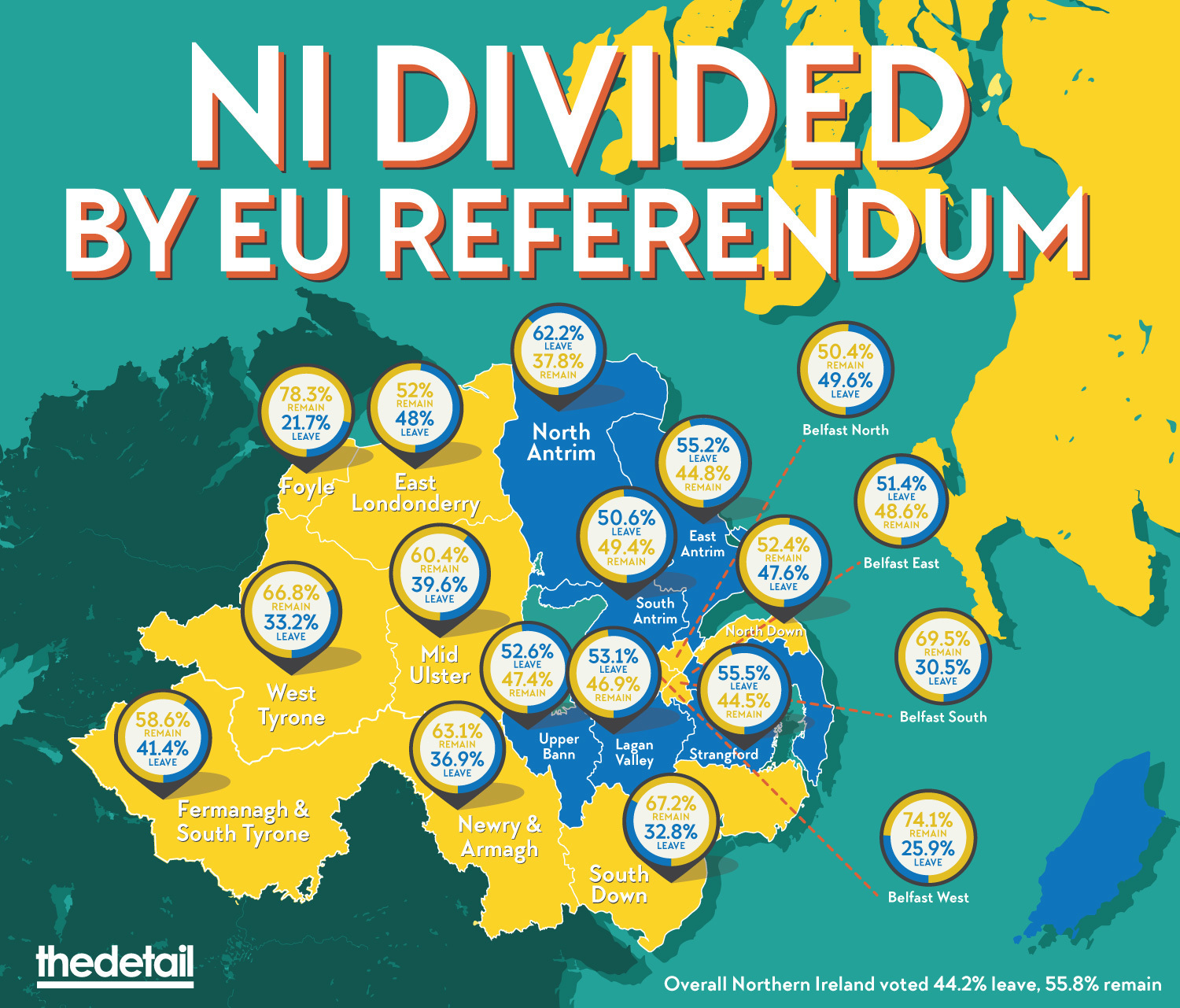

In the UK's referendum on EU membership in 2016 England and Wales voted to leave, but Scotland voted to remain in the EU, as did Northern Ireland by a majority of 56% to 44%.

Unionist parties in Northern Ireland are supporting the Brexit process, insisting the entire UK must leave the EU as a bloc.

Irish nationalists have enjoyed closer links with the rest of the island as a result of the peace process. They are calling for Northern Ireland to have special status within the EU, amid fears that Brexit will create a hard border with the Republic of Ireland which remains an EU state.

The tensions have already contributed to the recent collapse of Northern Ireland’s cross-community government and have led to calls by Sinn Féin for a referendum on Irish unity.

The peace process ended major violence, yet successive British and Irish governments have failed to put systems in place to heal the legacy of the conflict. The Troubles claimed over 3,500 lives, left at least 50,000 injured, an estimated 200,000 bereaved and a similar number traumatised.

Meanwhile, low level violence remains a concern. Between 2006 and 2015, there were 22 killings by illegal paramilitaries, more than 1,000 shootings and bombings, 787 so-called punishment attacks, and nearly 4,000 cases of people being forced from their homes.

High levels of deprivation have previously contributed to instability. A report by government experts warned Brexit could cause major economic damage, but the document remained secret, until it was published by The Detail here.

ANALYSIS

For more on demographics see here

The divisions that continue to exist beneath the surface of the peace process may be largely unknown outside Northern Ireland.

There are locations on the map where the divisions are less pronounced, but even where the degree of separation is sharp, it should not be simply read as evidence of animosity.

While sectarianism is undoubtedly an aspect of life in Northern Ireland, the patterns also show ordinary communities on a difficult journey away from divisions that they inherited.

The north of Ireland is a place where people are living through the remnants of divisive British and Irish history.

The map covers towns and cities transformed by the success of the peace process and which are positive places to live.

Valuable cross-community work is building reconciliation and the physical separation shown on the map is sustained by a range of factors, including sharply divided public sector housing.

But Brexit risks raising tensions over sensitive issues including national identity.

British and Irish cultural traditions are reflected across the society, often in ways that may not be obvious to outside observers.

The vast majority of Catholic and Protestant children are taught in separate schools, but while the educational divide is often expressed in solely religious terms, schools can reflect the Irish/nationalist or British/unionist identity of communities they serve.

The vote in favour of Northern Ireland remaining in the EU drew support from both communities, suggesting there may be broader backing for special arrangements for the region as Brexit unfolds.

European governments have pledged to take account of the complexities of the peace process, but a wider debate on the way ahead may be required, as Brexit risks opening-up divisions in Northern Ireland.

How can a shared future for all communities be carved out of the current crisis?

- The Detail is publishing expert analysis on division from Belfast-based academics Paul Nolan & Ciaran Hughes (available here), while Kevin McNicholl writes on the Northern Irish identity (available here). The map was produced by software engineer and data analyst Dr Matthew Doherty.

This project has received support from the Northern Ireland Community Relations Council which aims to promote a pluralist society characterised by equity, respect for diversity, and recognition of interdependence. The views expressed do not necessarily reflect those of the council.

By

By