SINN Féin has faced claims for a long time that the Catholic middle class may be wary of voting for a united Ireland - but has the DUP risked isolating affluent unionists by its support for Brexit?

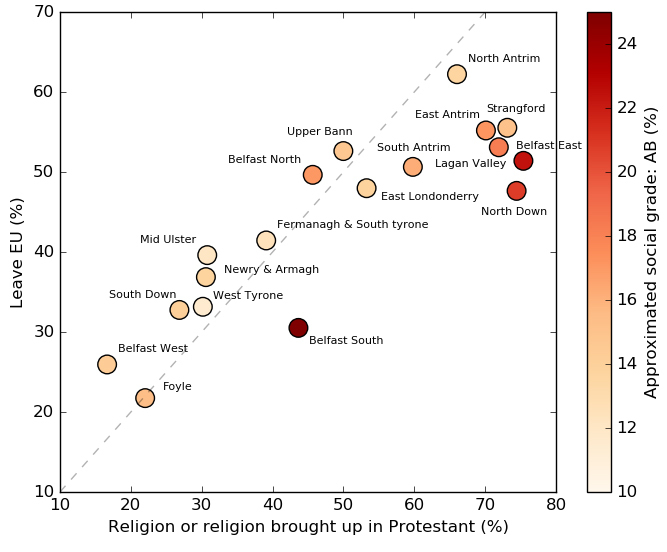

The graph above illustrates a trend identified by Belfast-based data analyst Matthew Doherty, showing that while unionist constituencies voted in large numbers to leave the European Union (EU), the wealthiest unionist communities showed less enthusiasm.

North Down, South Belfast and the unionist heartland of East Belfast emerged as outliers that broke away from the trend.

They returned relatively lower levels of support for leaving the EU than other areas with large unionist populations - but can that be explained by the fact that the three constituencies have the highest concentration of middle class residents in Northern Ireland?

Matthew Doherty said: “The dashed line on the chart indicates where a constituency should lie if all members of the Protestant community - and no one else - had voted as a bloc to leave the EU.

“In the data we can see that most areas lie close to this line, however it's striking that the few areas that don't are the most affluent unionist areas."

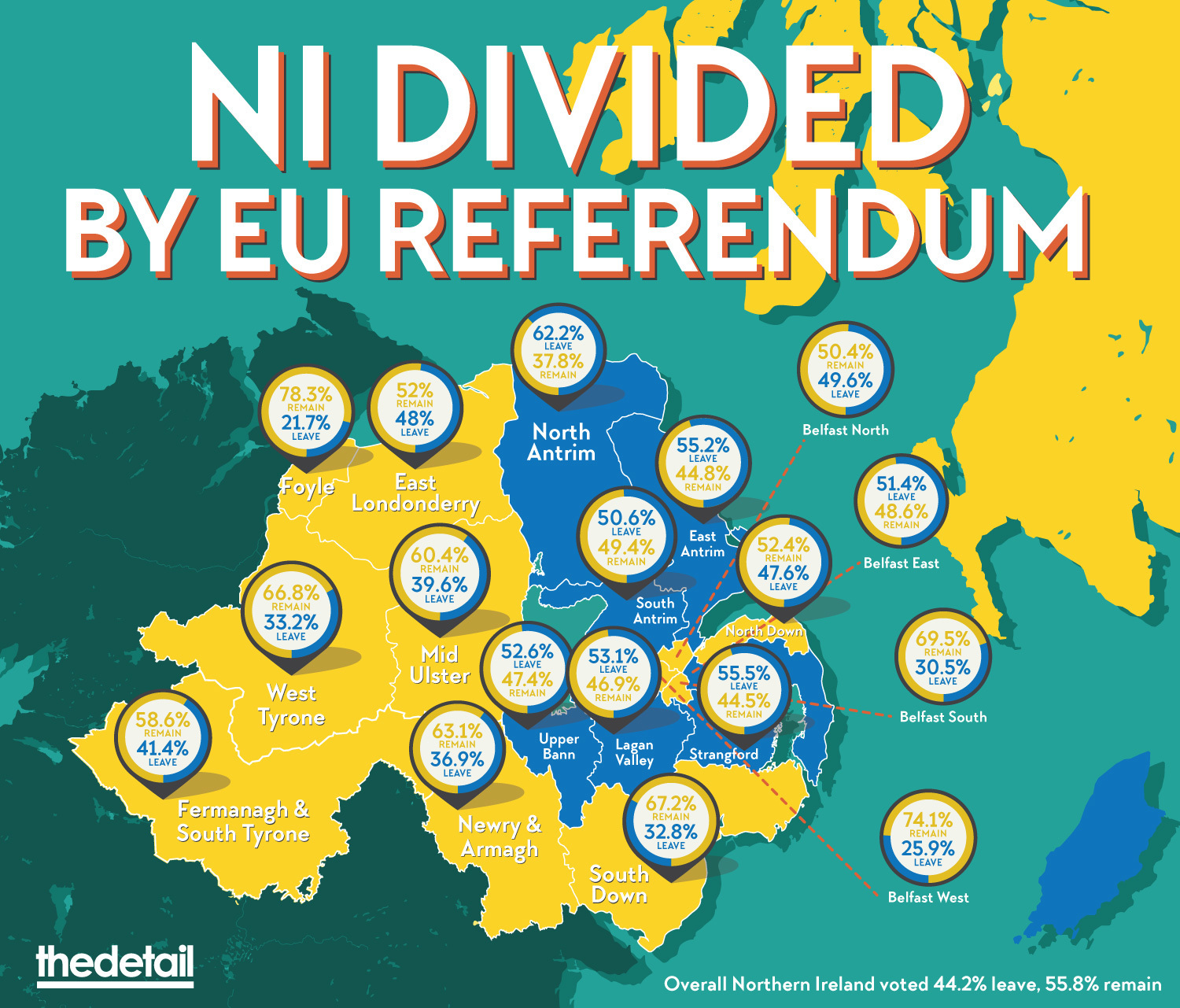

While England and Wales voted to leave the EU, Scotland voted to remain, as did Northern Ireland by a majority of 56% to 44%.

Northern Ireland divided on broadly 'orange and green' lines, with greater support for EU membership among nationalists than unionists, but there was still a cross-over on either side of the debate.

During the referendum campaign the nationalist SDLP, Sinn Féin and the cross-community Alliance party called for the UK to stay in the European Union.

The Ulster Unionist Party also backed remaining in, but it was undermined by senior members who instead called for the UK to leave the EU and to secure new trade deals "with our former colonies".

The DUP championed a Brexit vote with calls to “take our country back”.

But did some unionist voters see such slogans as emotional appeals, rather than a fully thought-out strategy?

THE NUMBERS

Data compiled by government shows the employment status of people across Northern Ireland – including those in senior managerial, administrative or professional occupations, which represent the leading AB social category.

Areas with higher Protestant/unionist populations voted in greater numbers for leaving the EU.

But North Down, South Belfast and East Belfast – the constituencies with the highest concentration of AB voters - fell outside the pattern in unionism.

Lagan Valley is another predominantly unionist constituency which has the fourth largest AB population. It also saw a lower 'leave' vote than might have been expected.

An additional chart, shown below, illustrates the shifting levels of the AB population in all 18 constituencies and how each area voted.

The significance of the trend in unionist constituencies shouldn't be overstated, but it raises questions about how sections of unionism might react as the implications of Brexit unfold.

And while governments in London, Edinburgh, Dublin and beyond are trying to steer events to their advantage – Belfast has been left standing.

STORMONT STUMBLES

It wasn’t until four days after the Brexit vote – long after Scotland had already reacted to events - that Stormont finally creaked into action with the announcement that civil service teams are being set-up to examine the implications.

Politicians in the Assembly who campaigned for Brexit were no better prepared than those at Westminster.

Now it is unclear how the 3.5billion euros that the EU has earmarked for Northern Ireland for 2014-20 will be affected.

That could yet have implications for tens of thousands of employers, groups and projects.

And while Stormont's existing plan for creating new jobs hinged on lowering Corporation Tax, that could also have been put at risk by the Brexit decision.

DEEPER QUESTIONS

Away from Stormont, a panel of academics at Queen’s University in Belfast identified key questions raised by the Brexit vote, but to which there are currently no answers:

- What does the UK want from Europe and what will it get?

- How many years will it take to agree complex new trade deals around the globe, given that Whitehall has as few as 25 experienced trade negotiators, compared to around 600 in Brussels?

- Will the UK Treasury replace the billions the EU invests in farming and rural communities?

- Will the poor reputation for environmental protection in the UK, and especially in Northern Ireland, get better or worse without the pressure of EU fines?

- How will the international fallout from Brexit affect more extreme political movements across Europe?

- Can Scotland secure special status within the EU, and if not, will voters risk opting for independence?

Back at Stormont, there are divisions over how to react, with deputy First Minister Martin McGuinness supporting the regional vote to remain in the EU, while First Minister Arlene Foster insists the UK-wide decision for a Brexit is final.

WHAT NEXT?

The British government is working hard to take the heat out of the referendum crisis and will look to the Irish government as a potential ally in future EU negotiations.

That could also become more complicated, if the unstable Dublin administration faces an early election over the next two years, as opposition parties such as Sinn Féin were already predicting.

That issue is a reminder that politics across Ireland and Britain was already in a state of flux, even before the EU crisis erupted.

The atmosphere of post-referendum panic could calm down and so it would be foolish to make wild predictions about the time ahead.

But if voters in Northern Ireland had hoped for a period of stability, they must now fear that the future has been left at the mercy of events.

See also: Brexit brings fresh division to Northern Ireland's fragile politics

By

By