LOWER staffing levels in child and family services in the Republic of Ireland than in Northern Ireland have sparked calls for greater investment.

It has emerged that there are three times more child and family social workers per head of population in the north than in the south.

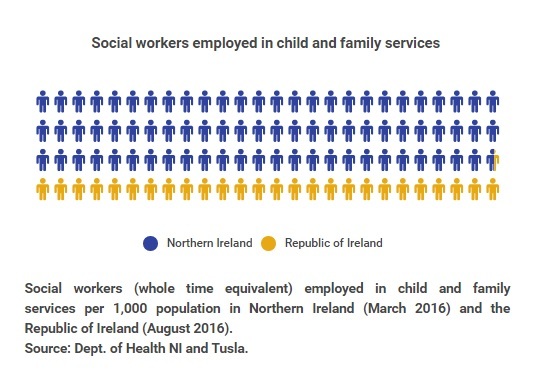

Staffing figures obtained by The Detail show there were 1,919 social workers employed across child and family services in the north compared to 1,612 (including temporary staff) in the south last year.

Taking the population difference into account, the figures suggest there was one social worker in child and family services per 1,000 population in the north compared to one social worker per 3,000 population in the south.

The figures come as The Detail also reveals a fourfold difference in the rate at which children at risk of abuse or neglect are identified and monitored by child protection services north and south - click here for full story.

The disparity in frontline staffing levels has prompted concerns from children’s rights watchdogs on both sides of the border.

"There is a much lower number of social workers per head of population in the south. This raises a concern as to whether we can get done what we would like to get done,“ the Ombudsman for Children in the republic Dr Niall Muldoon told The Detail.

"I have said on many occasions, and I will repeat it again, Tusla needs more resources to provide the best possible service for children,“ he added.

The Commissioner for Children and Young People in Northern Ireland Koulla Yiasouma said the “disparity” in staffing levels between the two jurisdictions was surprising. The fact that children’s social services in the north are under-resourced, she said, raised further questions for services in the south.

“I have made comparisons with the other jurisdictions of the United Kingdom and Northern Ireland is found wanting,” the NI Children’s Commissioner said.

“If we’re found wanting with those jurisdictions [in the UK], and the jurisdiction next to us is found wanting when compared to us, it does beg the question what is happening in the south?” she added.

The threefold difference in frontline staffing levels in child and family services, north and south, is illustrated in the graphic below.

Child protection services are provided by five Health and Social Care Trusts in the north and by a dedicated child and family agency, Tusla, in the south.

There are some differences in child and family services in both jurisdictions. For example, social care agencies in the north also provide services for children with a disability. On the other hand, Tusla in the south also provides services under the National Education Welfare Board and other child specialist services.

Click here for further information on services provided and total staffing numbers in child and family services in both jurisdictions.

The figures come as children’s social services on both sides of the border are under pressure and under-resourced.

Among the challenges are children without an allocated social worker and waiting lists for assessment in the south and unassessed cases and unfilled posts in the north.

Our analysis reveals the following:

- There were 20 occasions during 2016 where children on the child protection register in the south did not have a social worker.

- Over 5,000 cases in the south, involving child protection concerns or children in care, did not have an allocated social worker in December 2016.

- In the past three years more than 1,600 child protection referrals in the south were not recorded as being screened - raising fears that children are being "lost in the system".

- Plans to introduce mandatory reporting of child abuse in the south have been delayed until later in 2017, one year later than planned.

- As of March 2016, 379 cases relating to family support services remained unassessed or “unallocated" in the north.

The gap in staffing resources between jurisdictions also come as The Detail reveals a fourfold difference in child protection registration rates north and south.

The National Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Children (NSPCC) in Northern Ireland said the number of social workers in child protection services was likely to have a bearing on the number of children on the child protection register.

“If you were to increase the number of staff employed in statutory social care services you would probably have an impact on the number of children on the child protection register,” Colin Reid, policy and public affairs manager at NSPCC Northern Ireland, said.

MORE SOCIAL WORKERS NEEDED

Social workers in child and family services on both sides of the border are feeling the pressure, according to representative organisations.

The Irish Association of Social Workers said Tusla is under resourced and challenged by a high number of staff vacancies and difficulties in recruiting and retaining staff.

“Tusla is especially struggling to retain staff and as a result it is providing a more crisis-driven service than one able to support families who are experiencing difficulties at an earlier stage and so prevent the potential later crisis. This further adds to the pressure of social workers who can be more attracted to other social work posts,” chair of the association Frank Browne said.

Acknowledging these difficulties Tusla confirmed that a recruitment campaign is ongoing. The agency is working towards a target of recruiting an additional 268 social workers between 2016 and 2018.

The scale of the recruitment challenge facing Tusla is highlighted by the fact that the agency is losing around 150 social workers every year through retirements and staff leaving the service.

Tusla lost an estimated 177 social workers last year and looks set to record an underspend in pay costs of over €3 million for 2016.

This year the service expects to recruit 230 social workers but also lose around 168 leading it to forecast a net increase of around 62 social workers by the end of 2017.

Minister for Children Katherine Zappone has acknowledged that recruitment challenges will “continue to be difficult” in the coming years.

Minister Zappone also confirmed that Tusla and the department are taking part in a health workforce planning initiative, which will make recommendations to the Health Minister in June and will include planning the “appropriate supply of social workers”.

Meanwhile the Northern Ireland Association of Social Workers (NIASW) has called for an additional 330 social workers to address staffing pressures across health and social care services.

The call to fill existing vacancies and employ additional staff follows a recent ‘Above and Beyond: At what cost?’ survey by the NIASW, which also revealed that staff in children’s social services were more affected by staffing pressures.

The association confirmed that a higher proportion of staff in statutory children’s services (55%) reported vacancy rates compared to staff in other social care programmes (50%). A higher proportion of social workers in children’s services (93%) also reported regularly working unpaid hours compared to social workers in other care programmes (88%).

There is a “logical” need, the NI Commissioner for Children said, for a sufficient number of social workers to meet demand: “I cannot see any other way of improving the wellbeing of our young, particularly the mental health of our young people, unless we invest additional resources.”

CAPACITY CONCERNS IN THE SOUTH

In the south, concerns over staffing vacancies and resources allocated to Tusla are well documented.

Financial and staffing resource issues have been flagged by the United Nations Committee on the Rights of the Child – click here to read more - and by the Health and Information Quality Authority (HIQA), which regulates and monitors child protection and welfare services.

There were 20 occasions during 2016 where children on the protection register did not have an allocated social worker. The Department of Children said in "most" of these cases children were subsequently allocated a social worker and otherwise interim measures were put in place.

However, there are thousands of other children without an allocated social worker. These are children who have been assessed by social services as requiring protection or are in care.

In 2016 Tusla sought to more than halve the number of ‘unallocated cases’ to less than 2,700 by the year end. And while the agency made some progress during the year, figures for December reveal there were 5,413 unallocated cases - twice as many as the year-end target.

The Ombudsman for Children said one unallocated case is one too many. “It is not good enough that in December 2016 there were more than 5,000 unallocated cases. More staff are needed to support huge demands on the service,” Dr Niall Muldoon.

“If enough resources are not in place it potentially leaves children in a very vulnerable position and we need to change that by putting in place the required resources to deliver the appropriate level of response,” he added.

A question mark over whether every child protection referral is screened or checked by social services prompted further concerns for the Ombudsman, who warned that vulnerable children may be lost to the system as a result.

Dr Muldoon was commenting on figures, illustrated below, showing that over 1,600 abuse and neglect referrals were not recorded as screened or receiving initial checks in the past three years.

Tusla data also shows that child protection screening rates ranged from 70% to 100% across service areas.

Child protection concerns are initially checked or screened through a preliminary enquiry process to determine the extent and nature of the concern.

The child and family agency said initial screening may not be required where a referral “does not fall under child protection or isn’t within Tusla’s remit” and that such referrals are passed on to appropriate organisations.

The Department of Children, however, confirmed there are anomolies in how some service areas are recording referrals.

“Some areas continue to include referrals that are not related to child protection in their returns of child protection referral data”, a spokesperson for Minister Zappone said, adding that these referrals were not subject to a preliminary enquiry.

"All referrals which require a preliminary enquiry receive one. Tusla has advised that this issue will be addressed fully in the roll out of the National Child Care Information System," they added.

The Children’s Ombudsman said reporting inconsistencies must be addressed: “It’s never been clear if the same steps are undertaken in each service area or that every child has an equal opportunity for intervention, support, and protection.

“The figures ... support my concerns that children may be lost in the system and that there are cases where children are being lost between services.

"If there is no preliminary enquiry or a child is diverted to other services we need to know where they are going. At the moment it is unclear where children are being diverted to," Dr Muldoon said.

PRESSURE POINTS IN THE NORTH

Pressures also exist in child and family services in the north with official figures showing that some referrals are not being assessed and remain ‘unallocated’.

At the end of March 2016 there were 379 ‘unallocated’ cases across child and family services in the five health trust areas – none related to child protection concerns and most related to family support services.

The “high risk” posed by unallocated cases has featured on the corporate risk register of Health and Social Care Board (HSCB), which oversees the governance and performance of health and social care trusts, for the past five years.

To address the issue, the Department of Health has come under pressure from the Northern Ireland Association for Social Workers (NIASW) to act on its recommendations for more staff.

“The existence of unallocated cases where children referred to Health and Social Care Trusts are awaiting assessments of need underscores the importance of the Department of Health and social work employers acting on NIASW’s recommendations for change as a matter of urgency,” Marcella Leonard, chair of the association, said.

CURRENT AND FUTURE CHALLENGES

The ongoing staffing and funding challenges facing Tusla come as the Irish state’s record on child protection has been brought into sharp focus by a number of controversies and investigations.

This year alone has seen two investigations established to examine alleged shortcomings in the child protection system in the recent and distant past.

In March a commission of investigation was established to examine how an intellectually disabled young woman, ‘Grace’, was left in foster care for 20 years despite allegations of sexual and physical abuse.

Tusla has also come under the spotlight for its involvement in a controversy over false child abuse allegations against a Garda whistleblower, which has led to a tribunal of inquiry.

Meanwhile a commission of investigation into mother and baby homes is shining a light on another dark chapter in Irish life, as harrowing details emerge about the deaths of hundreds of babies and the broken lives of children and their birth mothers at these institutions between 1922 and 1998.

Inquiries and reports into the state’s failure to protect children are nothing new. Since the 1990s, more than 550 recommendations have been made to the Irish government to address the failings of the state to protect children - click here to read more.

The Minister for Children said “the majority” of these recommendations have either been addressed or implemented or have been overtaken by developments in the sector.

Minister Zappone added that service providers are held to account by “a robust framework of standards and regulations”.

There is still a long way to go, however, the Children’s Ombudsman said, noting that one in four complaints to his office in 2015 were about Tusla. The most common complaints related to the handling of child protection concerns, care services for children, and support for families in the system.

"Like many others, I am extremely concerned and distressed by the recent, high profile child-protection cases that have come into the public domain. As Ombudsman for Children, my priority is to ensure that Tusla is operating effectively to protect the most vulnerable children," Dr Muldoon said.

“Based on the regular interaction my office has with Tusla, I have real concerns about the inconsistencies that exist within the agency. I am not convinced that the necessary learning from mistakes is taking place. It’s important that Tusla operates in a way that protects the child rather than the system,” he added.

MANDATORY REPORTING

Meanwhile Tusla is facing further challenges this year with the planned introduction of ‘mandatory reporting’ under the Children First Act, which was signed into law in November 2015.

When enforced the new requirement will mean all professionals working with children must, by law, report any protection or welfare concern they may have about a child.

The Children’s Ombudsman said additional resources will be needed to support the roll out of the new reporting requirement.

“We do expect the number of child protection and welfare referrals to increase but we can’t be quite certain to what extent,” Dr Muldoon said, adding that many people had already become familiar with the system and were reporting concerns.

“But we would expect there to be an increase for a period and we should be planning for that and putting the necessary resources in place,” he added.

Tusla, however, is bracing itself for "a substantial increase in referrals" and has sought more staff and resources to prepare for mandatory reporting.

While the emphasis this year will be on "preparation and readiness", Tusla said mandatory reporting "will result in significant pressure on already stretched social work duty and intake teams across the country".

The Department of Children said full year costs do not arise in 2017 as the "full commencement" of mandated reporting will only commence in December. "It is expected that any additional resource requirements for Tusla, including for the roll out of mandated reporting, will be dealt with in the context of 2018 budget discussions," a spokesperson said.

GREATER INVESTMENT

Meanwhile in the north, the Commissioner for Children said more resources and investment should be made in children’s social services.

Commissioner Yiasouma noted that Northern Ireland has the lowest spend on children’s social services across the United Kingdom.

The average spend on social services for every child aged 5-19 years was £761 across the UK in 2013/2014; in Northern Ireland the spend per head was £501 that year – click here to read more.

Additional resources, the NI Commissioner said, are also required to deal with emerging issues and challenges, such as child sexual exploitation and online abuse.

“I know it’s not helpful in this current climate … to talk about greater investment but I cannot see any other way of improving the wellbeing of our young, particularly the mental health of our young people, unless we invest additional resources,” Commissioner Yiasouma said.

Click here to read The Detail's story on the gap in children at risk rates in both jurisdictions.

By

By