THE 1998 Belfast/Good Friday Agreement and the resultant Independent Commission on Policing for Northern Ireland (the Patten Commission) brought about extensive reforms designed to enhance the accountability of policing. These included the reform of the Royal Ulster Constabulary (RUC) into the Police Service of Northern Ireland (PSNI), an independent police complaints mechanism (the Office of the Police Ombudsman for Northern Ireland), the establishment of an independent policing authority (the Northern Ireland Policing Board).

The Patten Report explicitly recommended that these principles should apply to covert policing. Despite this the British Government, in a paper appended to the 2006 St Andrews Agreement, set out “future national security arrangements in Northern Ireland” which shifted the most sensitive areas of covert policing in the opposite direction, effectively ring fencing them outside the post-Patten accountability arrangements. The policy formalised the previously largely undeclared role of the Security Service (MI5) in covert policing in Northern Ireland and actually transferred primacy to MI5 for ‘national security’ covert policing, with the PSNI playing a seemingly subordinate role.

Transparency over covert policing policy, codes of practice, legal and ethical standards envisaged by Patten and provided for in international standards sit uncomfortably with an agency which has a culture of operating entirely in secret. In December last year, five years on from the transfer to MI5, CAJ published the ‘Policing you do not see’ a report scrutinising covert policing accountability, and in particular the controversial subject of running paramilitary informants. The report found it is effectively impossible to tell if the agents MI5 runs and the agency itself operate within the law. The research reflected that what international standards and the Patten reforms promised were both strict publicly available policy guidelines setting out the acceptable boundaries of agent activity and robust and powerful external oversight mechanisms to ensure the rules were abided by. The report concluded, however that neither was in place for MI5.

The extent to which the intelligence gathering system directs, facilitates or permits agents to be involved in crimes has long been the subject of controversy. All police services operate informants. The question is the extent they operate them within the rule of law, including the parameters set by human rights obligations. It is difficult to see how anyone in the 21st century could argue that policing bodies should just be trusted to operate without rules, or have rules that no one can actually enforce. The case both for clear policy and oversight bodies with the powers to enforce it is clear, and is particularly relevant to covert policing in this jurisdiction given what has happened here in the recent past.

On three occasions from 1989 to 2003 John Stevens, who became Commissioner of the Metropolitan Police and is now a member of the House of Lords, led separate police investigations into allegations of RUC collusion with loyalist paramilitaries. Stevens defined the elements of collusion as “the wilful failure to keep records, the absence of accountability, the withholding of intelligence and evidence, the extreme of agents being involved in murder” Among his conclusions were “Informants and agents were allowed to operate without effective control and to participate in terrorist crimes.”

In his Collusion Inquiry Reports into deaths in the late 1980s and 1990s the retired Canadian Judge Peter Cory concluded there was an attitude which persisted within RUC Special Branch and the British Army’s Force Research Unit (FRU) “that they were not bound by the law and were above and beyond its reach.” The Police Ombudsman, Nuala O’Loan’s 2007 ‘Operation Ballast’ report into RUC Special Branch collusion with the north Belfast UVF revealed police intelligence reports and other documents, mostly rated as “reliable and probably true” which linked police agents and one informant in particular to ten murders. Among the other matters recorded in Ballast were failures to arrest informants for crimes to which those informants had allegedly confessed; subjecting informants suspected of murder to lengthy sham interviews and releasing them without charge and falsifying or failing to keep records and interview notes.

Ballast also found RUC Special Branch were not adopting or complying with the UK Home Office Guidelines on matters relating to informant handling and did not comply with the Regulation of Investigatory Powers Act (RIPA) when it came into force in 2000. The report concluded that such practices, far from being isolated, were likely to be systemic. The Ballast investigation ran from 2002 and noted that as a result of concerns the PSNI had conducted reforms. This included the introduction of new policy frameworks and a 2003 review of informants, which resulted in around a quarter of informants being let go, half of them as they were deemed “too deeply involved in criminal activity.”

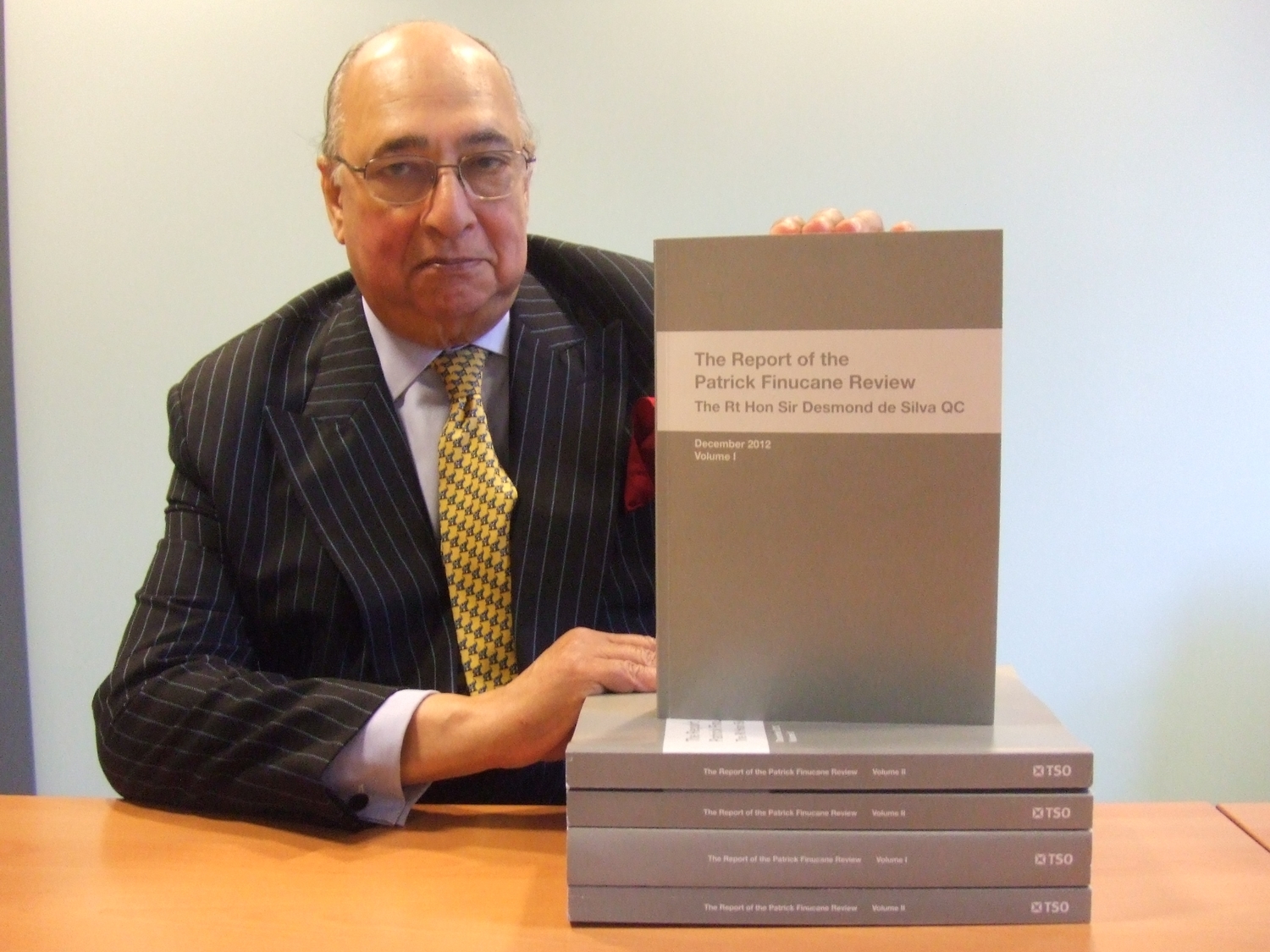

As is well known, de Silva was not the public inquiry promised into the death of human rights lawyer Pat Finucane, nor, as the family have stressed, did the desktop review get to the bottom of his murder. More broadly in his report de Silva, whilst finding collusion in the case, is keen to adopt a narrower definition of collusion than that harnessed by Judge Cory in his collusion enquiries, and to conclude that he does not think collusion was a matter of government policy. However, the documents De Silva references and declassifies in relation to the policy framework used to handle paramilitary agents are very enlightening, and themselves question such a conclusion.

In relation to the policy framework in general for running agents de Silva concludes RUC Special Branch “had no workable guidelines”, FRU’s Directives and Instructions were “contradictory” and MI5 had “no effective external guidance to make clear the extent to which their agents could be permitted to engage in criminality”. Pointing the finger at government, de Silva concludes there was a “wilful and abject” failure to provide the “clear policy and legal framework necessary for agent-handling operations to take place effectively within the law.” What is even more enlightening is the narrative of the various initiatives to set up such a framework where agents could operate outside the law.

First, declassified documents explicitly confirm that this was the modus operandi of running paramilitary informants at the time. Records of a high level RUC–NIO meeting in March 1987 confirm the approach was “placing/using informants in the middle ranks of terrorist groups. This meant they would have to become involved in terrorist activity and operate with a degree of immunity from prosecution.” The system also involved holding back information from the judicial processes to protect informants. The record concedes that all this was “technically” in breach of guidelines. The RUC therefore advocated for more “realistic guidelines”.

It is not that the UK government did not have any policy framework relating to running informants at the time. There were Home Office Guidelines. However, the RUC worked outside them, regarding them as “totally unrealistic/unworkable for dealing with terrorism”. Similarly MI5 “did not consider itself bound by those guidelines”. MI5 did have its own internal instructions which did provide for agent criminality.

The 1987 RUC request for “realistic guidelines” which in effect would have reduced to writing the policy of running agents outside the law was met with a “not overly enthusiastic” response by the NIO. The then UK Attorney General, Patrick Mayhew, was concerned his “officials should not participate in the drawing up of guidelines which condone the commissioning of criminal offences.” In this correspondence from March 1988 the Attorney appeared content for prosecutors to use their “discretion” not to prosecute informants for crimes they had committed but drew the line at putting in writing guidelines in which the authorities would have authorised offences being committed in advance.

The RUC subsequently conceded that this was issue was a “hot potato” for the NIO as they were reluctant to be involved in formulating such a system. This was despite, the RUC noted, “the fact that what actually goes on is known or assumed” and legally, the RUC argued, the NIO were not being asked to approve agent criminality beyond what was already the case. In correspondence the NIO Secretary of State acknowledged the RUC wanted guidance that would permit paramilitary informants “to take part in serious crime” under the supervision of senior RUC officer when “certain criteria” were met.

Further documents indicate the NIO was keen to draw out and fudge the process. The NIO did work on a revised set of Guidelines which in the view of de Silva “did not…represent the tightly defined framework (coupled with rigorous regulation to prevent abuses) that was required.” Indeed it is recorded that the Solicitor General in 1992 regarded the thrust of one key passage as, in effect “Don’t get caught”, and hence was “unpromising territory for Ministerial approval.” Whilst there was no formal Ministerial stamp on the guidelines they, or at least an adapted version of them, were nevertheless adopted for internal use by MI5 and subsequently RUC Special Branch and the successor unit to FRU.

At this very time the fallout of the trial of Brian Nelson led to government having to conduct a review of agent-handling. Nelson, a FRU agent within the UDA, was sentenced to ten years imprisonment in 1992 having pleaded guilty to twenty offences including five counts of conspiracy for murder. The agent-handling review was conducted by John Blelloch, a former NIO Permanent Secretary. Minutes indicate Blelloch also dismissed the national standard in the Home Office Guidelines as “unacceptable” in the Northern Ireland context and did not advocate legislating as he believed it would be “politically unobtainable”. Blelloch did endorse the content of the new NIO Guidelines, but recognised the problem of the “status of the document” in the absence of ministerial approval. The then Attorney General reiterated to the government working group responding to Blelloch that he would “not approve any guideline which appeared to condone in advance the commission of serious criminal acts” [emphasis added]. Also recorded is an earlier creative proposition from the then NIO Secretary of State that the agents might not after all be guilty of crimes they commit as a:

“…criminal offence requires a criminal mind: for all practical purposes no offence will be committed by an agent whose act is not accompanied by a criminal mind- that is to say a mind desirous of the commission of the relevant offences.”

Unsurprisingly the Attorney General did not feel such a proposition was likely to stand up in court. The Attorney stated there may be a case whereby agents’ participate in crimes with the intention of frustrating them, but not when participation in a crime is undertaken just to maintain cover to help the security forces generally.

Government therefore found itself in a conundrum. It appeared to wish the modus operandi of agent handling outside the law to continue but did not want to put it into writing. In testimony from retired senior RUC officer to de Silva they argue in effect that there was “reluctance to give official recognition to what SB was doing, the effect of which would be to authorise agents of the State to allow informants to take part in activities that could lead to the commission of terrorist offences.”

The officer states that the gist of the response from government was “carry on what you’re doing but don’t tell us the details.” The narrative presented by de Silva indicates that government were not entirely sure of what to do to address this “unsatisfactory” situation– indeed a Home Office briefing note in 1994 optimistically hoped “the policy issue will be quietly laid to rest” in the context of the IRA ceasefire. A future government did legislate in 2000 to provide the first legislative framework for running agents under the Regulation of Investigatory Powers Act (RIPA). Interestingly in views similar to those previously expressed by CAJ de Silva does not see RIPA as effectively regulating the activities of agents stating: “…it is doubtful whether RIPA or any of its associated Code of Practice provides a real resolution to these difficult issues given that it provides little guidance as to the limits of the activities of covert human intelligence sources.”

This is not to say that de Silva necessarily believes permitting paramilitary agents to operate outside the law is collusion per se or that the practice should never be permitted. There is an undertone in the report that such a policy can be somehow legitimate and justifiable provided it is well regulated and controlled.

As set out in our MI5 research CAJ and other human rights groups have taken the opposite view: that the state operating outside of the rule of law – as set out in human rights standards relating to impunity, effective investigation and remedy– fuelled, prolonged and exacerbated the conflict. Going back to government’s conundrum, the present situations is that primacy for ‘national security’ covert policing has been transferred to MI5 where it remains impossible to tell the extent the secret agency is operating within or outside of the law.

Daniel Holder is Deputy Director of the Committee of the Administration of Justice (CAJ)