THE extradition process "could become toxic” if the European Arrest Warrant (EAW) is lost as a result of the UK’s withdrawal from the EU, a senior civil servant has warned.

A Detail Data investigation has found that in the past ten years hundreds of EAWs have been sought to extradite suspects in high profile cases - which have included murder, rape, human trafficking and terrorism - into and out of Northern Ireland.

Documents prepared by the Northern Ireland Department of Justice (DOJ) which were obtained by Detail Data under the Freedom of Information Act reveal that the department believes: "For practical law enforcement the maintenance of the European Arrest Warrant system is essential."

Experts interviewed by Detail Data confirm that there is currently no replacement for EAWs post-Brexit, while our research reveals that extradition agreements currently in place between the UK and non-EU countries have significantly lower success rates than the EAW.

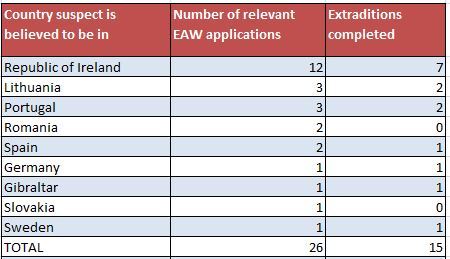

The data revealed that the majority of EAWs sought by the Police Service of Northern Ireland (PSNI) related to suspects believed to be located in the Republic of Ireland.

Speaking to Westminster's Northern Ireland Affairs Committee in December 2016, PSNI Chief Constable George Hamilton has said the EAW is "essential in tackling terrorism, organised and volume crime across the island of Ireland."

Groups representing victims of crime have also raised concerns, including the children's charity, the NSPCC.

The organisation's Colin Reid said: "We simply do not know what this would be replaced with and whether there would be much more complexity around the north-south movement of dangerous people."

He added: "The important thing is timely access to justice – so any delay is not in the interests of children both psychologically or actually in terms of their recovery from their experiences."

There are two main types of extradition process. The first is the European Arrest Warrant introduced in 2004 which allows a country to seek the return of a suspect from every other European Union (EU) region with the issuing of a single request.

The second relates to extradition requests to nations outside of the European Arrest Warrant area, which requires individual bilateral agreements between countries.

Our investigation of this issue has found that:

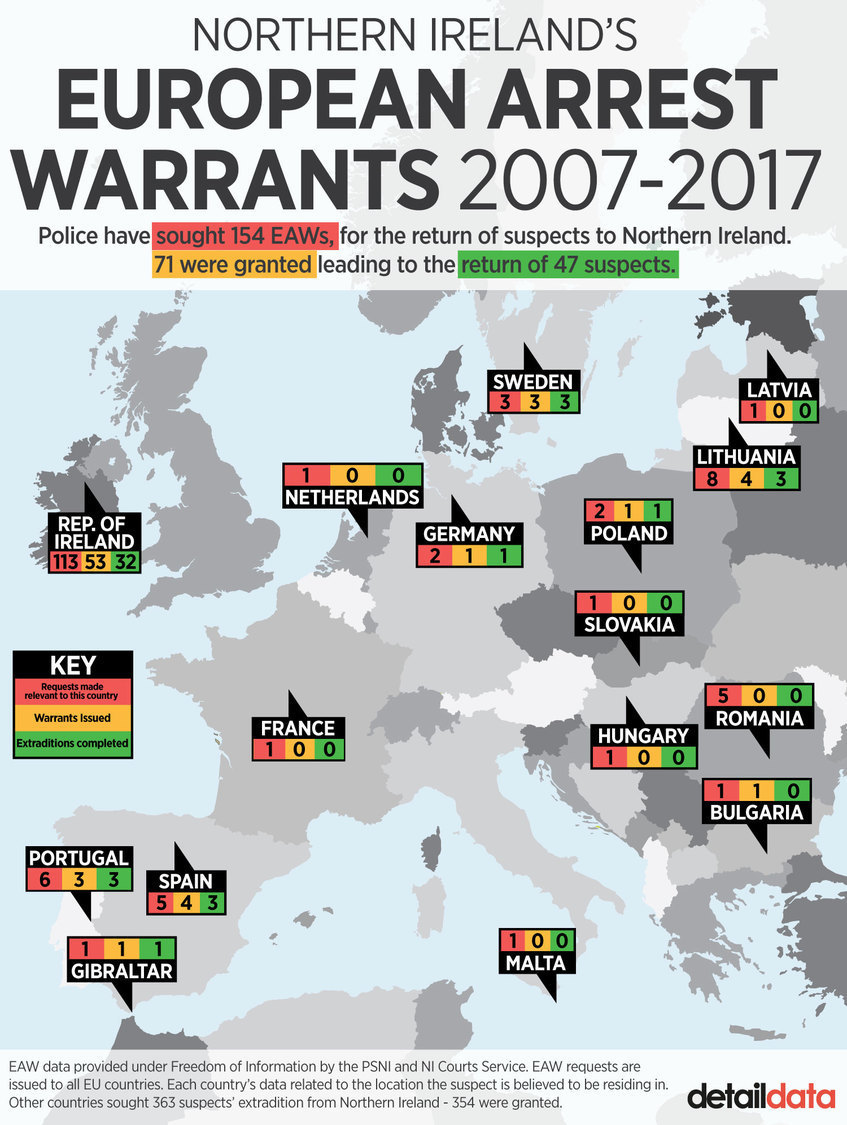

- The PSNI sought 154 EAWs between January 2007 and May 2017. Of these, 71 warrants were granted, leading to the extradition of 47 suspects back to Northern Ireland.

- The EAWs were sought in relation to offences such as Breach of Licence (13 cases), rape (10), murder (7), human trafficking (2) and terrorism (2).

- The overwhelming majority of the PSNI applications (113) were for extradition of suspects, believed to be in the Republic of Ireland, back to Northern Ireland.

- Of the 154 suspects, 143 were male.

- Meanwhile, a total of 14 non-EAW extradition requests were made to countries including Australia (6), Bangladesh (2), Brazil (1), India (1), Norway (2) and the USA (1). These were for crimes including rape, murder, GBH and fraud. Of the 14 requests, just two led to extraditions.

- Between January 2007 to March 2017 the Northern Ireland Court Service granted 354 extradition applications to countries pursuing suspects believed to be located in Northern Ireland. The courts data does not state how many were EAWs or which countries had sought the extraditions.

Detail Data’s research revealed that 31% of EAW requests by the PSNI resulted in the extradition of a suspect, while there was only a 14% success rate using the extradition agreements in place with non-EU countries.

In July, the Northern Ireland Assembly published a research paper outlining three potential options for the replacement of the EAW post-Brexit.

- Using the 1957 European Convention on extradition to govern the process.

- That 27 new bilateral agreements be struck between the UK and EU member states.

- That a new surrender agreement is struck with the EU.

In a statement issued to Detail Data, the Republic of Ireland's Department of Justice said it would not state its position on the future of extradition with the UK ahead of official discussions on the matter.

"Both Ireland and the UK make extensive use of the measure," it read.

"The arrangements for the surrender of persons is an issue which will fall for consideration in the context of negotiating the terms of the future relationship between the EU and the UK.

"It would be inappropriate to pre-empt discussions on that future relationship."

According to Victim Support NI chief executive Geraldine Hanna, the loss of the EAW could mean: "Difficulty from the police's perspective in terms of bringing someone back to face justice, leading to more delays, frustration and a lack of justice for victims.

"Delay can have a range of impacts on the victim. Largely it means the length of time it takes to get to court will impact upon their ability to fully recover from the crime because it is still hanging over them. There can be a range of emotional and psychological difficulties."

The European Commission states that an EAW may be issued by a national judicial authority if: "The person whose return is sought is accused of an offence for which the maximum period of the penalty is at least one year in prison" or "he or she has been sentenced to a prison term of at least four months."

The Commission adds that EAW: “Replaced lengthy extradition procedures within the EU's territorial jurisdiction. It improves and simplifies judicial procedures designed to surrender people for the purpose of conducting a criminal prosecution or executing a custodial sentence or spell in detention.”

Although the Commission has stated that no decision on the UK’s access to EAW post-Brexit has yet been made, in March Westminster's EU Home Affairs Sub-Committee launched an inquiry to “explore the issue through a specific case study of the options for replacing the EAW after the UK leaves the EU.”

On October 31 Minister of State, Ministry of Justice Dominic Raab told the House of Commons that: “We do want to continue vital extradition relations with our EU partners.

“We start from the position of the European Arrest Warrant, with strong, intensive co-operation on extradition, and we will make sure we continue that operationally for many years to come.”

TOXIC

Following the June 2016 vote for the UK to leave the EU, Sir Malcolm McKibbin, the then head of the Northern Ireland Civil Service, requested that the permanent secretary of each Stormont department compile reports “identifying, as best we can at this early stage, the implications of the EU referendum result”.

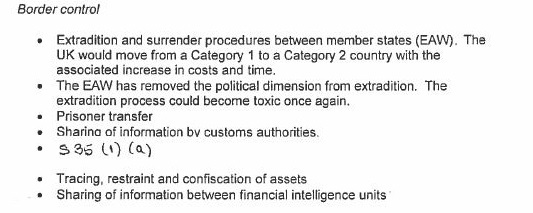

In response, DOJ, whose permanent secretary is Nick Perry, submitted a document which states:

“Extradition and surrender procedures between member states (EAW). The UK would move from a Category 1 to a Category 2 country with the associated increase in costs and time.

“The EAW has removed the political dimension from extradition. The extradition process could become toxic once again.”

This document was secured by Detail Data via a Freedom of Information request.

When asked to expand upon what was meant by the term 'toxic', a DOJ spokesperson said: "The Department has nothing further to add to the response it issued [via FOI] on 28 September 2016."

However, a second DOJ briefing paper, prepared a year after the Brexit vote, in June 2017, reiterates the department's reliance on the facility.

"The UK's departure from the EU raises various practical policing and justice issues specific to this jurisdiction because of the land border," it reads.

"These include maintaining the current high levels of operational cooperation between the PSNI and the Garda, sustaining effective criminal justice cooperation.

"For practical law enforcement the maintenance of the European Arrest Warrant system is essential."

NEGOTIATIONS

According to solicitor Ruairi Gillen, who specialises in extradition issues, in the absence of a deal on EAW, the issue of extradition will become more complicated post Brexit.

"As it stands, day one after Brexit if we no longer have EAW, if you don’t know in which country the person is, where do you start to look for them?" he said.

"If it goes and we then have to look for individual treaties, then it is going to be much more difficult for UK authorities to keep on top of those people who are requested -particularly in this jurisdiction, where we have a land border.

"Some of the terms that have been bounced around are that Northern Ireland could become a safe haven for criminals. At the moment I’m not sure that there is any evidence that would suggest that that might not be a by-product of coming out of the EAW."

Paragraph 11 of the European Council guidelines for negotiations on the UK's exit from the EU refers to 'flexible and imaginative solutions' to dealing with problems arising from the Irish land border.

According to Queen's University Professor of European Politics David Phinnemore, this offers considerable scope for tackling issues such as the future of the EAW.

"I think the language is really interesting," he said.

"I don’t think we have ever seen such language before in terms of the willingness of the EU to think about flexible and imaginative arrangements for problems with an external partner.

"At the moment I think there is a strong willingness to exploit that language to address problems as raised in the negotiations. And if the UK were to raise the issue of the European Arrest Warrant and want to seek for it to continue to apply here (NI) as opposed to the rest of the UK then I think there is an opportunity to do that.

"Whether that would then result in something bespoke for Northern Ireland would then depend on the negotiations. I think for an arrangement such as this, you would probably need to get all of the 27 to agree plus you would have the British agreeing as well.

"The fact that the language is there means there is an opportunity to at least seek a solution locally if Northern Ireland finds itself outside of the European Arrest Warrant as a result of Brexit.

"As for what the position of the British government is at the moment – it is unclear.

"At one level there are some quite loud voices advocating that the UK stays in the European Arrest Warrant because of the benefits it brings in terms of policing, extraditing people and in terms of concerns of how you would replace it.

"On the other hand there is a general expectation that if the UK were to stay in it would have to accept the jurisdiction of the court of justice which is proving politically very sensitive for the UK. So it depends in many respects which one of those preferences wins out and at the moment that is decidedly unclear."

THE DATA

Crossing the Irish border. The majority of EAWs sought by the PSNI have been from the Republic Photograph by Press Eye.

Analysis of data provided by the PSNI under Freedom of Information confirms that of the 154 EAWs sought since 2007, 71 warrants were granted, which to date have led to 47 extraditions.

This means a suspect has been returned to Northern Ireland in nearly 31% of cases.

EAWs have been sought in relation to offences such as Breach of Licence (14), rape (10), murder (8), human trafficking (2) and terrorism (3).

The overwhelming majority of applications (113) are for extradition of suspects believed to be in the Republic of Ireland back to Northern Ireland. Between 2007-2017 a total of 53 of these warrants have been issued leading to 32 south to north extraditions.

By comparison, a total of 14 non-EAW or Category 2 extradition requests were made to countries including Australia (6), Bangladesh (2), Brazil (1), India (1), Norway (2) and the USA (1). Of these, just two warrants were issued (in the Australian cases). Both of which were actioned.

This means a suspect was returned in just 14% of cases – less than half the success rate of the EAW.

Detail Data has previously reported on difficulties relating to cross-border policing and justice highlighting that, in the continued absence of a North-South deal on police ‘hot-pursuit’ more than 47 police chases were terminated at the border between 2011 and 2015.

The Court Service has also confirmed that it has processed applications from other countries for the extradition of 363 individuals from Northern Ireland since 2007, granting 354. The court data does not state how many were EAWs, which countries had sought the extraditions and in how many cases an extradition subsequently followed. However, it is understood that Poland accounts for a large number of these requests.

Data published by the Irish Government states that between 2004 and 2015 the State executed 267 extraditions to the UK.

The State has also had 305 suspects surrendered to it by the UK between 2004 and 2015.

However, the report does not specify how many of these individuals were transferred from the north.

SEXUAL OFFENCES AND CHILDREN

Among the areas in which the EAW has been successfully used is in securing the return to Northern Ireland of suspects relating to serious sexual offences.

Over the past 10 years the PSNI has sought EAWs relating to rape (10), brothel keeping (1), child abuse (1), GBH/Rape/False imprisonment (1), historical sexual abuse (1), oral rape (1), sexual assault/burglary (1), sexual offences (8), indecent assault (1), unlawful carnal knowledge (1) and human trafficking (2).

EAWs were issued in 27 of these cases with suspects subsequently extradited in 17 - a return rate of 63%.

By comparison, in four cases where a non-European Arrest Warrant was sought for sexual offences in Bangladesh, India, Norway and the USA for rape (1), indecent assault (2) and attempted rape (1) no warrants were issued.

According to Colin Reid, the NSPCC NI policy and public affairs manager, groups representing young victims of crime have major concerns about the potential loss of the EAW - particularly in relation to the return of suspects from the Republic of Ireland (RoI).

"Like everyone we are trying to work out the implications of Brexit across the UK and particularly for us here in Northern Ireland," he said.

"We would see EAW as very important in the various structures we have to protect the public and to protect children from dangerous people and to ensure that those who have committed offences in this jurisdiction are returned from RoI where this is appropriate.

"We simply do not know what this would be replaced with and whether there would be much more complexity around the North-South movement of dangerous people.

"On sexual offending in particular, you often see people trying to leave the jurisdiction in a bid to avoid investigation by the authorities.

"The important thing is timely access to justice – so any delay is not in the interests of children both psychologically or actually in terms of their recovery from their experiences. So anything that brings further delay is not helpful."

PSNI Chief Constable George Hamilton has said the future of the EAW was for politicians and not police to decide.

"Clearly the UK’s decision to leave the European Union, and with that the various agreements and protocols including European Arrest Warrants, are something that at a political level needs to be worked through," he said.

"We stand ready to inform that debate from a professional policing perspective but ultimately the initiative on that will lie with politicians and we will tread a careful line around being helpful, because we want to continue to do our job, but not getting in to political space.

"A lot of that will be engaging in, presumably, bi-lateral arrangements on specific issues like European arrest or access to Europol/Interpol and so on.

"We are alive to these. So we are doing some thinking about this but we will take our lead from the political space."

The chief constable added: "These are largely political issues that have an operational impact. We stand ready to assist with that but we don’t want to cross the line in to political interference."

For more coverage from The Detail relating to Brexit, click here.

The data from this investigation can be found here.

By

By