DUP leader Arlene Foster with Boris Johnson at the DUP annual conference in November 2018. Photo by Kelvin Boyes, Press Eye.

WHAT harm could a border poll cause and what way is the right way to approach changes to the constitutional futures of the UK and Ireland?

The (new, less popular) Secretary of State could call a border poll in the next year and send the electorates to the polls to choose to either a) keep Northern Ireland (NI) part of the UK or b) unite with the rest of Ireland.

The most common arguments against doing this are that it is bad timing (perhaps fair, given that Stormont has just been tentatively re-established) or that asking people to choose their constitutional future will perpetuate divisions.

It may be reasonable to suggest we lack the political maturity to make such a call, given that since the 1998 Belfast Agreement, Stormont has only been up and running for just over half of the time.

Further, unionists exhibit concerns that Sinn Féin are a well-oiled political machine who use rhetoric and adaptability to win over new audiences. In this context, Sinn Féin could persuade undecided voters into a new Ireland.

Unionism, contrastingly, has not yet managed to articulate a political project which appeals to anyone outside of its own ranks. Indeed, some of its own ranks are looking uncertain and have begun to show an interest in liberal and green politics.

Given all of this, is there a way to have a public conversation about the democracy and governance of this island without undoing the progress made on building relationships?

In short – we have to have the conversation. Change is coming in some form. How it happens is another matter and something we have some control over. How we ask people to make decisions and the information which is provided to them will shape the quality of those decisions.

The recent upsurge in the use of citizens' assemblies across the UK and Ireland is evidence of that. The EU referendum vote was a good example of how complicated these choices are, and that the information environment surrounding voters is central to how we support citizens to sift through the options available to them.

Therefore, prior to, during and after the voting process, there should be opportunities for in-depth, reflective discussions about the future shape of the country, in whose interests it is organised and how decisions are made.

If our aims are to have a robust and mature public debate about our constitutional future whilst protecting the relationships we have with one another, I’d suggest that we don’t limit ourselves to a snapshot referendum with two choices available.

Instead, we should use this opportunity to carve out more creative ideas for how we govern ourselves, allocate resources, make decisions and relate to each another, both personally and across the regions. Representative democracy as we know it has significant deficits. If we are to begin a conversation about constitutional change, other worlds are possible.

These include non-territorial autonomy, joint authority, city states, direct democracy, participatory democracy or a federal system. No one system will guarantee a political utopia, but offering a broader range of options, alongside a deliberative process will increase the likelihood of better outcomes.

With the scale of the problems behind us (violent civil conflict, repeated political scandals, suspensions of political institutions) and in front of us (the climate crisis, the suicide epidemic and public housing shortages), why limit our political imaginations to two options?

The most recent NI Life and Times survey data shows that just over three quarters of participants align to an A or B option, that is, remain in the UK or unify with Ireland. However, the only options available were that NI stayed in the UK, joined Ireland or became an independent state, while 16% of those surveyed didn’t know what they wanted the political future to be.

The question around joint authority produced some interesting results, as 64% would either happily accept this or could at least live with it.

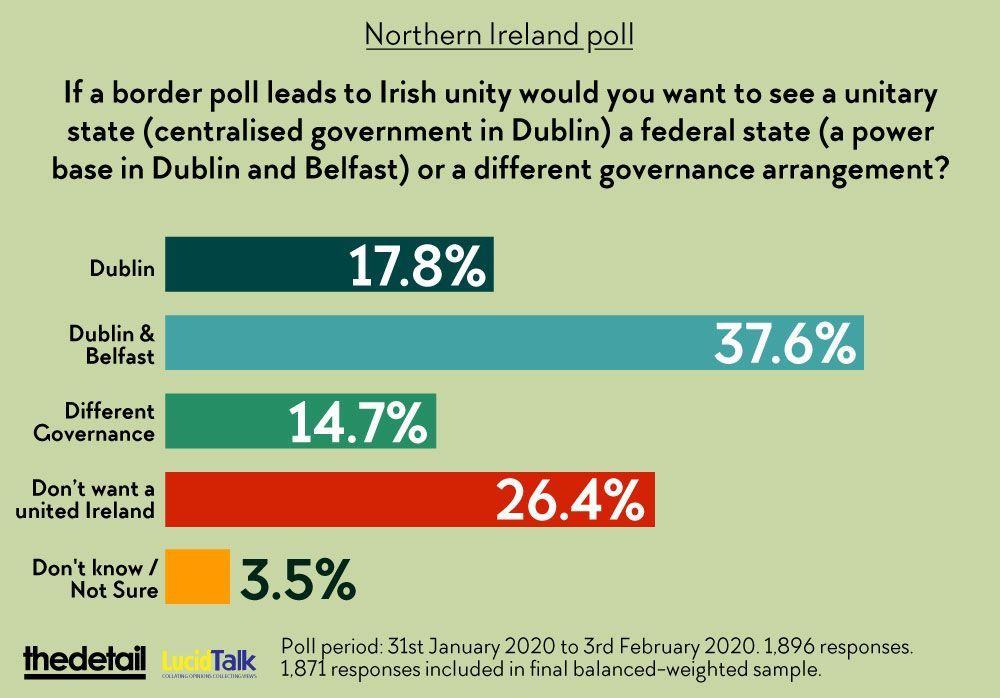

Similarly, the data produced for The Detail by LucidTalk show similar levels of support for more formalised governance-sharing between Dublin and Belfast. These results indicate that there are significant numbers in NI who feel political allegiance to the UK or Ireland.

What about those who don’t? Where are their choices on the ballot paper? How can we accommodate and reflect the reality that NI is home to multiple minorities?

Non-territorial autonomy (self-rule by a group sharing linguistic/cultural/religious identities who aren’t concentrated in one geographic area), whilst an under-utilised mechanism for governance, offers some remedy for the dispersed clusters of British and Irish-identifying people across NI.

At the very least, it could help mitigate minority concerns of being dominated at the hands of new majorities. Memories of past grievances and unsettled scores constantly threaten to derail political stability here.

A future constitutional settlement with any chance of being both successful and producing just outcomes must guard against that. Above all, this discussion requires the maximum amount of democracy. We can’t have another Brexit disaster before we get over the last one.

NI has comfortably navigated several major commemorations in the recent past – notably the Easter Rising and World War One centenaries. In the run-up to both, there was some apprehension around how celebrations and acts of remembering might undermine the project of peacebuilding.

If ‘one lot’ were paying homage to British soldiers while ‘others’ were commemorating those who sought to overthrow the British state, there was real potential for inter-communal splintering and the solidifying of ethno-sectarian identities.

For lots of reasons, that didn’t happen. Namely, preparation at political, academic and civil society levels some years in advance of the anniversaries.

I spent several years working with communities who were seeking more nuanced interpretations of British-Irish history and engaged in excavating under-explored aspects of the World War One.

This work, when done carefully and at a slow pace, can contribute to, rather than undermine, peacebuilding aims. It can highlight how we each carry multiple identities, which can change over time, and that can become more or less salient depending on with whom we come into contact.

In this way, the critical unsettling of what we held to be true about 1916’s major events, helped us to better understand one another.

As we approach the centenary of the creation of NI, the conditions which surrounded 2016’s commemorations are significantly altered. The fallout from the EU referendum has had a major impact on what was a fairly stable political settlement.

The March 2017 Assembly elections and June 2017 general election revealed that, far from being a unionist state, NI is populated by multiple minorities.

The unionist electoral majority, which for so many years carried with it the power to shape the cultural architecture of the state (statues, flags, place names and language) was diminished.

Unionism was further discombobulated during the fleeting DUP alliance with the Conservatives. From June 2017 to December 2019, unionism had, on the surface, direct access to the heart of the British political establishment.

This was unionism’s chance to put its case directly to the parent state, to whom it looked for support, resources, and ultimately, recognition of its devout Britishness. The ‘losses’ sustained over the past two decades (the disbandment of the RUC, changes to flying of the Union flag at City Hall, mandatory power-sharing with Irish nationalism, amongst others), deemed by some unionists to be unjust concessions for peace, could now be reversed.

As we know now, the temporary relationship between the DUP and the Conservatives was marked by mistrust, tension and disappointment. Whilst for some observers, this was surprising, for scholars of loyalism and unionism, both sides behaved exactly as we should expect.

From the 1970s and onward, both major British parties were treated with suspicion by Ulster unionism. In response, British politicians for the most part, have been confused by the cultural practices of unionists whilst simultaneously frustrated by the ability of Ulster unionism to cause them major difficulties.

In short, two groups who appear to be likely political allies instead view each other with hostility and mistrust.

This is in no small part due to the fact that, in NI, Britishness has been constructed in a different environment to how it has in Great Britain. Some unionists and loyalists argue that this is because they faced opposition to their culture from Irish republicanism.

Irishness in the north has, not dissimilarly, been forged in a hostile environment. There are some steps being made toward how to publicly accommodate both national identities. This work could be derailed by a border poll, if it is not conducted carefully.

- Sophie Long completed a PhD in politics at Queens University, Belfast and is Assistant Trust Secretary of The Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust.