A potentially historic general election is only days away but, despite months of campaigning in Northern Ireland, the big issues that will really shape our future aren't even on the agenda. A new project by The Detail's Steven McCaffery uses infographics to look at the major factors forcing change in Northern Ireland, as well as the stumbling blocks to progress.

YOU'VE heard it said a thousand times: "Politics never changes in this place..."

But it does. This society has been re-imagined since the decades of violence.

The pace of progress, however, has now slowed to a crawl.

Events over the last decade could only move as quickly as they were allowed to by political parties and by the British and Irish governments.

But there are now growing signals that factors outside the control of those same politicians are exerting pressure.

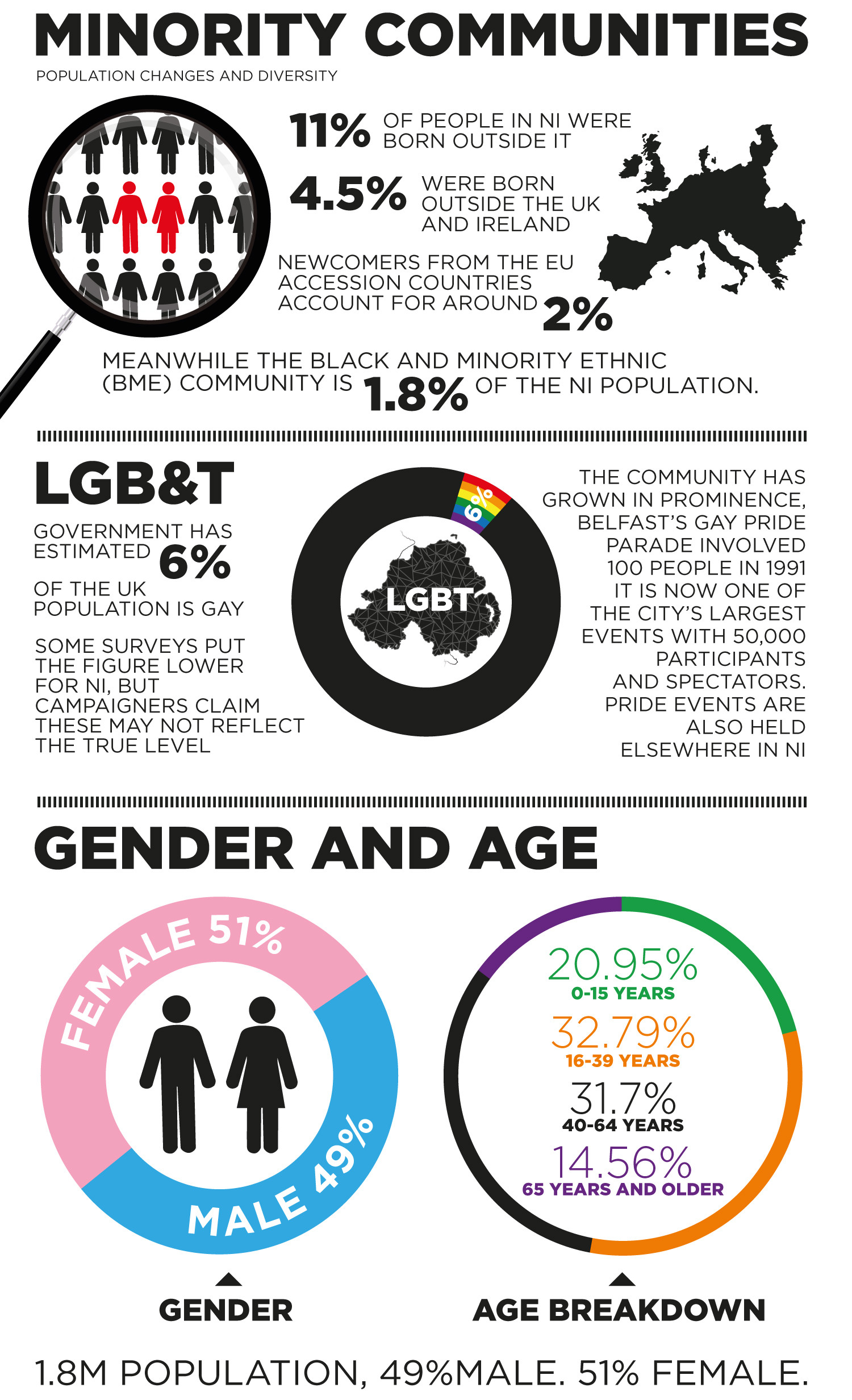

Major demographic shifts are being felt inside the Northern Ireland population, while upheaval in the Republic of Ireland and changes in Britain threaten to redraw the political map around us.

The problem is that none of these issues are being discussed.

New debates on the way forward are required for a part of the UK and Ireland that is still burdened by sectarian tension, political instability and a history of violence.

DEMOGRAPHICS - THE HAND THAT ROCKS THE CRADLE

Politicians promising the delivery of old certainties are either fooling themselves, or trying to fool you. Northern Ireland is a place transformed.

Established in 1921 amid the violence of the Irish War of Independence, its founders drew a line on the map to create the largest possible Protestant/Unionist majority inside the new state.

The partition of Ireland left small Protestant communities in an almost entirely Catholic state on the southern side of the new border, while Catholics in the fledgling Northern Ireland found the world changing around them.

The late 1960s saw the outbreak of the Troubles while, below the surface, the population had also started to slowly shift.

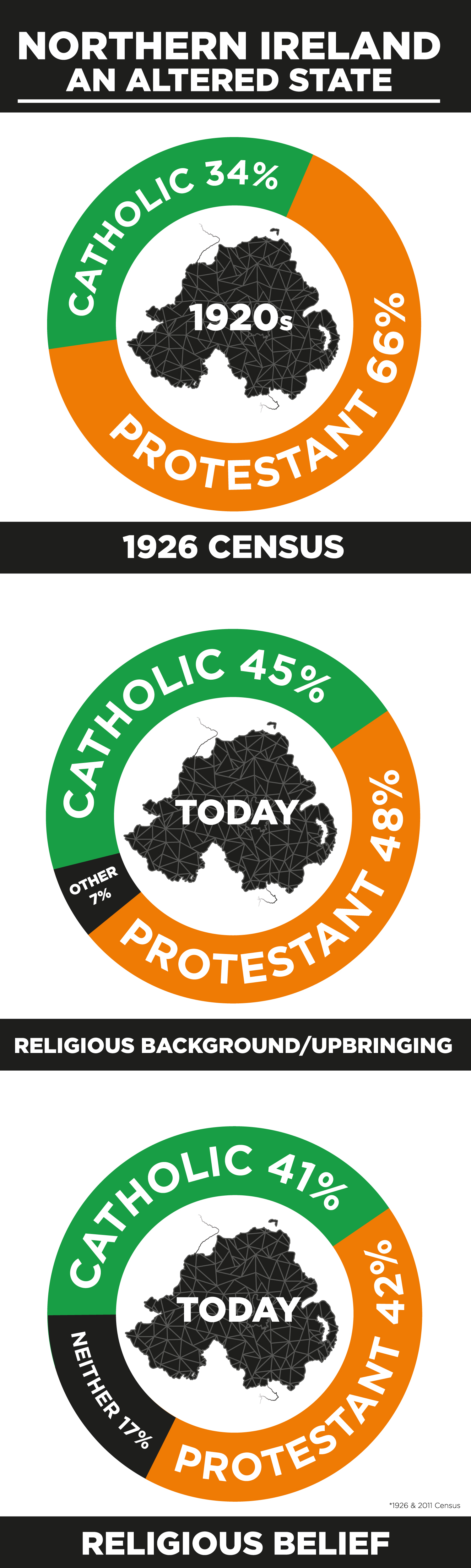

A tipping point came in December 2012 when census results showed that for the first time the Protestant population in Northern Ireland had fallen below 50%.

The Protestant population dropped to 48% and the rising Catholic population hit 45%.

The figures referred to religious background or upbringing, but census data asking people to state a current religion or religious belief, showed that an increased portion fell outside the two main blocs. A total of 17% did not state a religion or indicated they had no religion.

Religion broadly denotes political identity, but anyone who winces at sectarian headcounts can take comfort in the fact that the figures mean the future must be a shared one.

The data contains hard numbers that weigh-down on the plans of the major political parties: Unionists know continued change is inevitable, while republicans know their ambitions for Irish unity have to recognise the huge Unionist bloc.

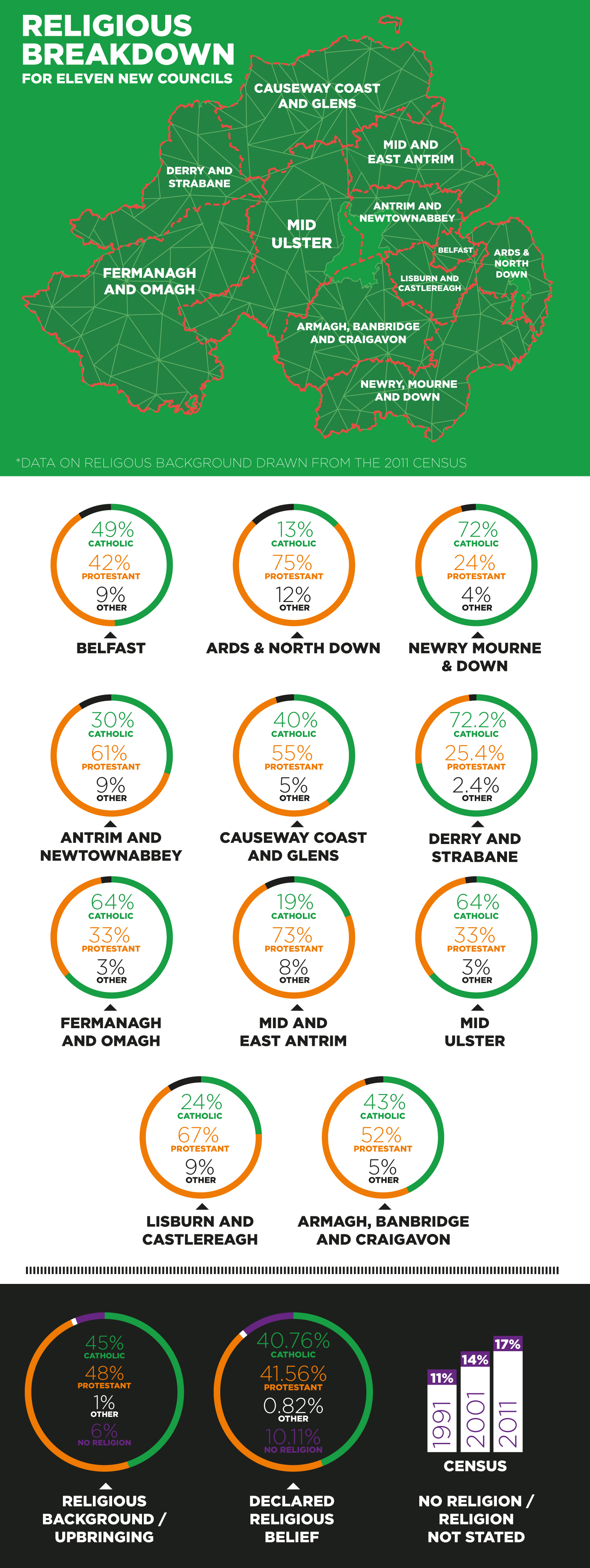

A closer look at the population statistics reveals that across the 11 local government districts, the controlling majorities shift between Orange and Green.

The pattern of majorities and minorities can be seen as a system of interdependence that demands overarching agreements.

But the failure of Stormont to deliver Northern Ireland-wide deals on issues such as flying the Union flag or the official use of the Irish language, has resulted in local councils going on solo runs over the status given to either British or Irish identity.

Meanwhile, Stormont is also failing Northern Ireland’s new minorities

BEYOND 'ORANGE AND GREEN'

Racist and homophobic attacks have increasingly grabbed the headlines since large scale violence slipped into history here.

So how have politicians reacted to these developments?

The first substantial race relations legislation reached Northern Ireland in 1997, just one year before the signing of the Good Friday Agreement.

Campaigners say that protections here now lag behind the rest of the UK.

A long-awaited Racial Equality Strategy, which should be Stormont’s key policy tool to tackle racism, is yet to be delivered despite Assembly pledges dating back to at least 2007.

Meanwhile, as far back as 2006 the Stormont administration gave a commitment to deliver a strategy to ensure support and equality for lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender people here, but that pledge was also delayed.

Despite ongoing consultations, support groups continue to demand the delivery of sufficiently robust measures to protect and promote the rights of new minorities.

Figures from the police show that hate crime is ongoing.

- 2005-14 there were an average 1,500 sectarian incidents and 1,000 sectarian crimes each year.

- 2004-14 there were an average 907 racist incidents and an average 663 racist crimes each year.

- 2004-14 there were an average 202 homophobic incidents and 136 homophobic crimes each year.

The data represents only those incidents that are reported to police and the true figure is likely to be higher.

Hate crime is a problem around the globe, but governments must be judged by how they respond.

Stormont’s failure to provide race and sexual orientation strategies arguably sends out a negative signal.

This is exacerbated by regular political rows over race and sexual orientation.

Why shouldn't Northern Ireland’s new minorities see existing safeguards broadened, so as to provide as wide a range of rights and protections as available elsewhere?

But, just as with demographics, the positive pressure of increased diversity is bubbling up through society.

The fracturing of old positions is also reflected in the census data on national identity in Northern Ireland, where the main findings showed that over 39% regarded themselves as British only, 25% as Irish only, and over 20% as Northern Irish.

On every front, we are a community of minorities, even if government is struggling to keep pace with the changes.

To view the infographic in full click this link NI full inforgraphic.jpg

WE SHOULD TALK...

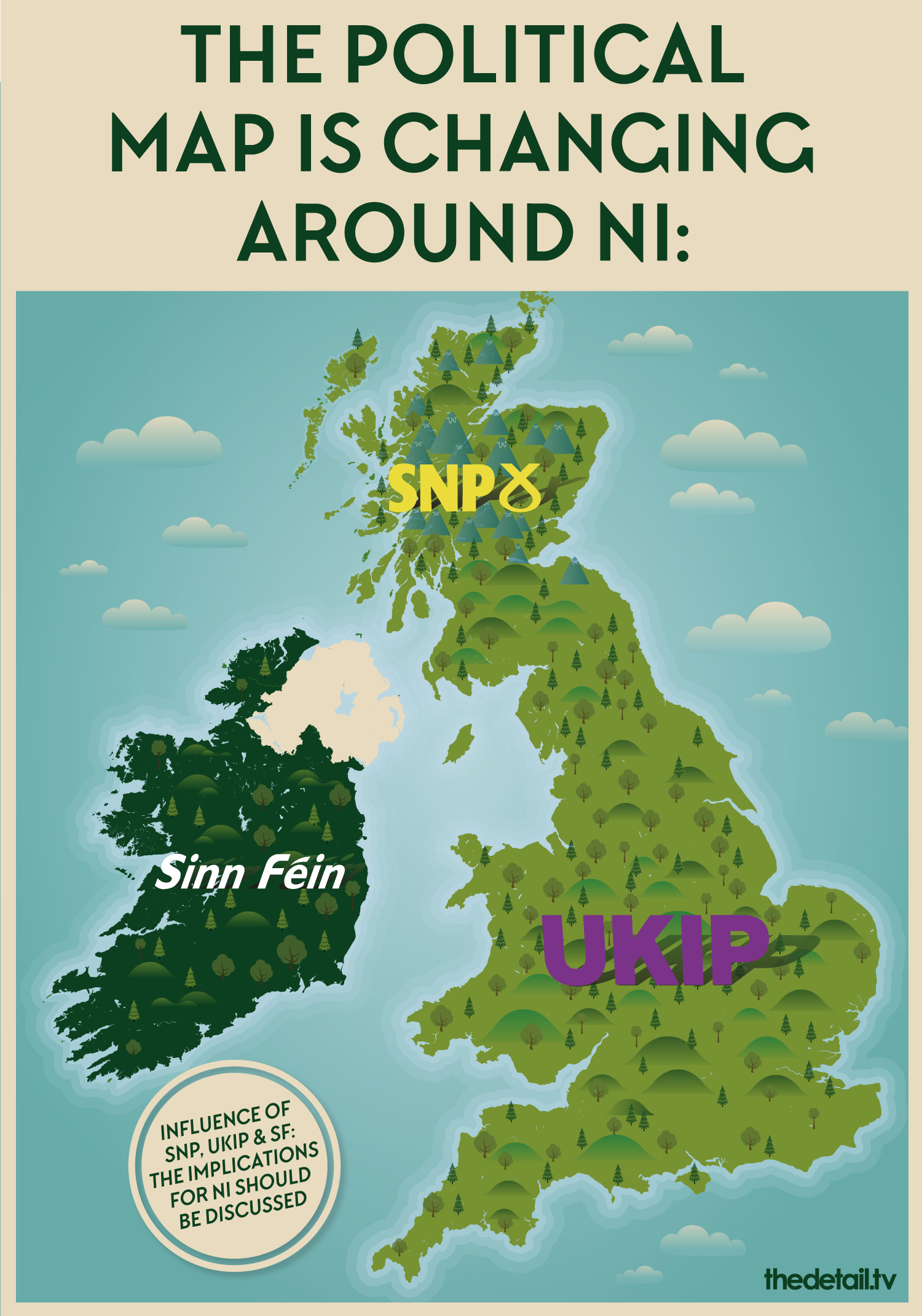

Change is already under way inside Northern Ireland, but change is also brewing outside its borders.

The SNP is growing in influence in Scotland and is pushing for greater independence from Westminster.

In England it is argued that UKIP, regardless of how it performs at the polls, is among those using its influence to push the Conservative Party on the issue of leaving the European Union (EU). That could give cause for concern in Northern Ireland, where the EU has invested over €7,533 million since 1988, and where the EU’s Single Farm Payment accounts for 87% of annual farm income.

And, on the southern side of the Irish border, Sinn Féin has emerged as a party with government ambitions over the next decade, which raises further questions for Northern Ireland politics.

All this is happening at a time when Northern Ireland has changed fundamentally since 1921. It is an altered state.

The population shifts and political challenges will only pose a problem if politicians continue to ignore them.

These pressures could instead be a spur for government to get serious about creating a shared future.

The data on population tells a potentially positive story of interdependence between unionists and nationalists, meaning that the future has to be based on compromise.

The Detail previously explored possible constitutional implications, looking at how joint-sovereignty by London and Dublin in Northern Ireland could emerge at some point as a potential outcome.

It's an option that chimes with the trajectory of demographics and may come to be seen as representing the fullest expression of equality for the competing British and Irish identities here.

But the political structures put in place by the Good Friday Agreement of 1998 mean that communities can be secure in the knowledge that they will decide their own future.

Whatever happens in the years ahead, however, it is clear that some new thinking will be needed.

Voters could begin by asking election candidates if they have a strategy for the future that stretches beyond polling day on May 7.

By

By