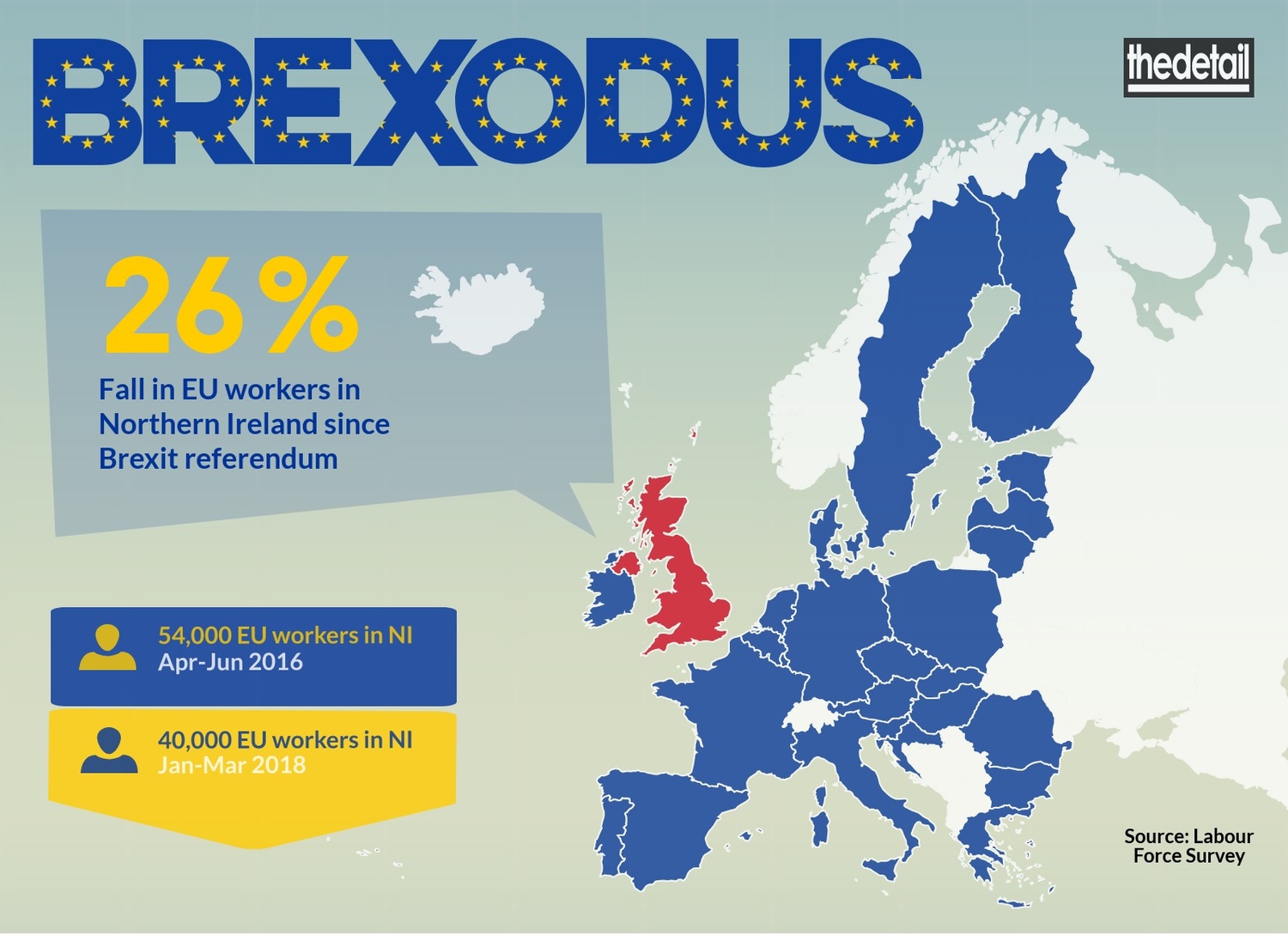

THE number of European Union workers employed across Northern Ireland has fallen by 26% since the UK’s Brexit referendum, new figures obtained by The Detail reveal.

As pressure mounts this week for a breakthrough in the ongoing Brexit negotiations with European Union (EU) leaders meeting for talks on June 28 and 29, The Detail can reveal a downward trend in the number of EU workers employed in Northern Ireland since the UK voted to leave the EU.

Labour force estimates provided by Northern Ireland’s Department for Economy (DfE) reveal there were 14,000 fewer EU nationals working in Northern Ireland by the end of March 2018 compared to the period of the June 2016 referendum, representing a 26% drop. The estimates do not include workers from the Republic of Ireland.

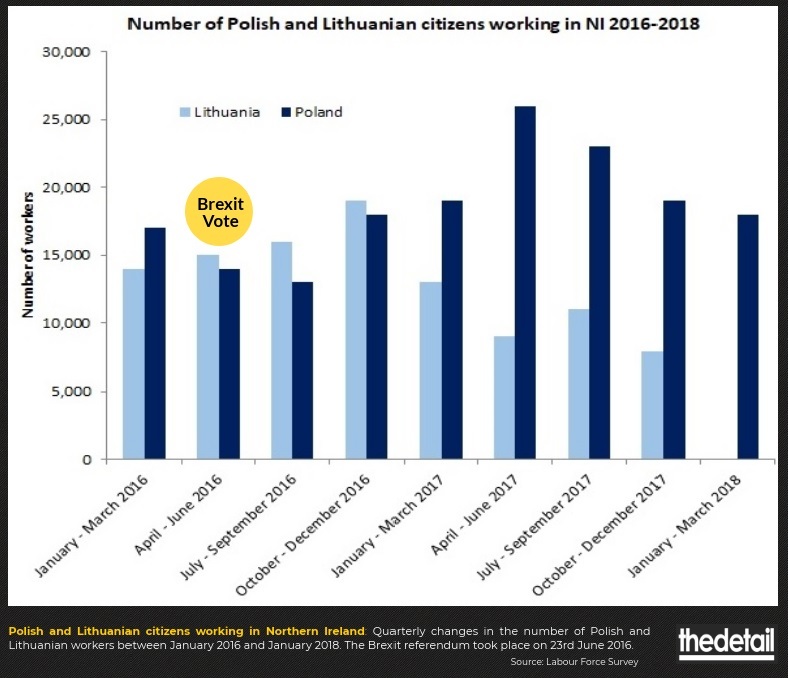

Other available estimates show a falling number of Lithuanian workers while the number of Polish workers has fluctuated since June 2016.

Honorary consul for Poland, Jerome Mullen said: “The falling numbers don’t come as a surprise to me because EU workers are not coming here and they’re not going to come. For EU citizens Brexit brings a lot of uncertainty.”

This comes as a DfE report published in March found EU migrant workers were the key driver in employment recovery and growth in Northern Ireland between 2008 and 2016. During that period the number of EU workers grew by 40,000.

A number of sectors in Northern Ireland are heavily reliant on migrant workers including manufacturing, the agri-food sector, hospitality sector, health and social care services, and retail and services sector.

A previously unpublished survey of agrifood businesses found 80% saw a fall in the recruitment of EU workers since the Brexit vote – see here for more details on the Northern Ireland Food and Drinks Association survey findings obtained by The Detail and concerns about recruiting staff.

Number of EU workers in NI since Brexit vote

The Department for Economy did not comment specifically on the fall in EU workers but noted that labour force estimates may be subject to volatility and seasonal fluctuations.

A spokesperson for DfE said: “The Department does not hold information on the reasons why EU migrants might choose not to come to Northern Ireland or choose to leave Northern Ireland.

“The Department is committed to creating a globally competitive economy that works for everyone. One of our main aims is to rebalance our economy and to have more people working in high income jobs. The Department uses the Skills Barometer to help plan its actions and policies to prepare for the projected future skills needs of the local economy.”

A Skills Barometer published by DfE and Ulster University in 2017 forecast that 80,000 jobs will be created by 2026 and that more than one third of these will be filled from a combination of graduates and migrant workers.

The figures, as revealed today, substantiate industry concerns that Brexit is having a negative impact on industry and contributing to a skills shortage in certain sectors.

Manufacturing NI said the fall in EU workers reflected what was happening on the ground and was of such concern that the organisation facilitated a meeting with a number of European honorary consulates in recent weeks.

Chief Executive of Manufacturing NI Stephen Kelly said: “These are very concerning numbers and reflect what we’re hearing from business – workers are leaving, not returning and firms are finding it increasingly difficult to recruit replacements.”

He added: “There is such concern that we recently brought together the Honorary Consulate’s for many Eastern European countries to discuss what can and should be done to ensure these valued colleagues feel very welcome in Northern Ireland.”

Honorary consuls for Poland and Hungary further told The Detail that EU workers were no longer coming to Northern Ireland and that the loss of migrant labour was contributing to a critical skills gap and recruitment challenges for businesses here.

Changing fortunes

Quarterly estimates for the number of citizens from each EU member state working in Northern Ireland could not be provided where figures fell below a reliability threshold of 8,000.

What figures are available, however, do show a changing picture for Lithuanian and Polish nationals working here.

As the graph below shows the number of Lithuanian nationals working here has fallen consistently since the end of 2016, while the number of Polish nationals – one of the biggest migrant communities in Northern Ireland – has shown greater fluctuation by rising and falling since the Brexit vote.

Number of Polish and Lithuanian citizens working in Northern Ireland since 2016

The figures did not come as a surprise to diplomatic representatives for Poland and Hungary in Northern Ireland.

Honorary consul for Poland, Jerome Mullen, said that while many Polish people had settled in Northern Ireland the uncertainty posed by Brexit had stemmed the flow of people coming to live and work here.

“The falling numbers don’t come as a surprise to me because EU workers are not coming here and they’re not going to come. For EU citizens Brexit brings a lot of uncertainty and as we go forward, and that uncertainty continues, the fall in EU workers is only going to get worse,” Mr Mullen said.

“Northern Ireland has seen thousands of Poles coming here to live and work. Many have settled here and will continue to stay while some will return to Poland but what has changed is the flow of workers from Poland; it’s not there anymore,” he added.

Mr Mullen added that higher wages in countries like Norway were proving attractive to many Polish workers: “I regularly receive requests from businesses to help source workers from Poland but I’ve not been able to access workers, even on good wage terms. In all cases I have come up dry”.

Honorary consuls for Poland and Hungary say EU workers are leaving NI

Honorary consul for Hungary, Ken Belshaw, said other factors were also at play: “We’re not seeing the same influx of labour from Eastern Europe as before and the key driver for that is a drop in the value of sterling. That’s a major indirect Brexit factor and it’s having an impact on whether people come here or not.”

Mr Belshaw, who is also founder of Grafton Recruitment which has 20 branches across the Czech Republic, Poland, and Hungary, added that many EU citizens were leaving Northern Ireland to return home to an improved economic climate.

He said: “People are leaving. Take for example Omagh, which has the largest settlement of Hungarians in Northern Ireland. The numbers peaked three to four years ago when there were 1,200 Hungarians working mainly in local engineering companies but now that number has fallen to 800”.

Both honorary consuls said the loss of EU workers is contributing to a critical skills gap and recruitment challenges for businesses in Northern Ireland in particular to fill joinery, electrical, and engineering positions, as well as in the hospitality sector.

Mr Belshaw warned: “We’re now at crisis levels for skilled jobs like welders, fabricators, and LGV mechanics. We’re not getting the same influx of skilled labour from Eastern Europe for these jobs and workers are not available locally.

“If a welder came into the office today we could auction him off because there is such a demand for skilled labour at the moment. We’re now at crisis stage and there’s an urgent need to get people into apprenticeships and onto the shop floor,” he said, adding that welders were now commanding a rate of £14.50 per hour, a considerable rise on the average rate of £10.50 per hour a year ago.

Mr Mullen added: “This skills shortage has arisen because, for years, the education system has failed miserably to invest in or promote apprenticeship programmes. The government that was in place was completely blind to the needs of industry as we looked ahead. I would say we’re beyond crisis point at this stage and that’s even before Brexit has happened.”

By

By