THE Good Friday Agreement was signed on April 10, 1998, marking the effective end of the Northern Ireland Troubles and delivering peace between nationalists and unionists. But beyond the traditional Orange and Green blocs, how did smaller ethnic minority communities experience the new era? The Detail’s Steven McCaffery reports.

THE peace process has been a success story, but like all stories, there are two sides to it.

The anniversary of the political deal carved out on that famous Good Friday 15 years ago has focused on the successful ending of large scale violence and the subsequent efforts to secure stable power-sharing government between former foes.

But a leading umbrella group for ethnic minorities says the people it represents have experienced increased violence since the emergence of the peace process, as well as a failure by the new Stormont administration to adequately respond.

Today The Detail examines the figures for attacks on ethnic groups and asks how politicians and the justice system have addressed victims’ needs.

The first substantial race relations legislation only reached Northern Ireland in 1997, just one year before the signing of the Agreement.

Now campaigners say a long-awaited Racial Equality Strategy, which should be Stormont’s key policy tool to tackle racism, has been “effectively frozen” since 2007 with the Office of First Minister and Deputy First Minister yet to deliver a new framework.

“Our experience of the Good Friday Agreement is one step forwards, two steps backwards,” says Patrick Yu, Executive Director of the Northern Ireland Council for Ethnic Minorities (Nicem).

“The issue here is that, with the Good Friday Agreement, we are talking about the two communities only.

“That is the trouble all the time.

“Others fall through the gap.

“We are agreed that the Good Friday Agreement benchmark was the cessation of all violence, but if you look at the organised racist attacks over the last ten year period, you have to ask why are paramilitaries continuing to attack ethnic minorities?”

RACISM HITS THE HEADLINESThe success in bringing the Troubles to an end in 1998 after decades of bitter conflict was hailed internationally, and while it represented a mammoth achievement, the more peaceful era soon showed evidence of a growing trend of racist attacks and intimidation.

Media coverage of incidents began to rise and a mood of public concern grew when some of the first hard data on the issue emerged in response to questions tabled in the House of Commons.

Those early figures showed racist incidents reported to police rose from a base of 25 in 1997, to reach 260 by 2000-01.

A string of factors was blamed – the end of large scale violence was helping attract greater numbers of economic migrants, they often chose cheap rented housing in deprived areas where far right groups sought to stoke tensions, and where the presence of paramilitaries added a menacing edge.

As a result of a series of headline-grabbing bouts of racist violence, often involving loyalist elements, Northern Ireland became controversially branded Europe’s ‘race-hate capital’.

The rates of attacks have remained high to the present day, however, statistics in the newly released Northern Ireland Peace Monitoring Report suggest current levels of racist crime are comparable, if not below the average rates in England and Wales.

But the same study notes that many racist incidents go unreported, while in Northern Ireland the presence of paramilitaries has heightened the fears of vulnerable communities.

Census figures published in December 2012 revealed that while Catholics were once Northern Ireland’s minority community, they are now reaching level pegging with those from a Protestant background.

Today, Northern Ireland’s `new minority’ is its ethnic groups and its growing community of economic migrants.

And reviewing the last 15 years from their perspective provides an alternative history of the Good Friday Agreement.

A NEW CYCLE OF VIOLENCEThe Belfast agreement brokered in 1998 did not mark the end of Northern Ireland’s turbulent history, but the beginning of a new twist in the political rollercoaster of the peace process.

By 2003 the agenda was dominated by the efforts of the British and Irish governments to revive the stalled power-sharing government, when fresh Assembly elections saw the DUP and Sinn Féin top the poll, representing a significant step in their rise to power.

The peace process brought with it a new lexicon, introducing unfamiliar words such as decommissioning and D’Hondt. New phrases also peppered reportage, with calls for “all-party talks”, “parity of esteem”, “power-sharing” and warnings of “no guns, no government”.

But the year also stands out as the first moment of the post-Agreement era when the issue of race attacks gripped the popular mind for a sustained period.

The news agenda bristled with reports of frightening incidents across Northern Ireland.

The episodes were widespread: a Muslim family forced to flee their Co Armagh home after an attack by a mob armed with baseball bats, a Portuguese man beaten unconscious on the street in Co Tyrone, an African man beaten in the face with a brick in Belfast and two pregnant women forced from their homes.

There was a debate about how society should respond, and calls for greater legislative protections.

Attacks were taking place in a wide range of localities, both traditionally nationalist and unionist, but a number of themes emerged including the frequency of attacks in loyalist areas.

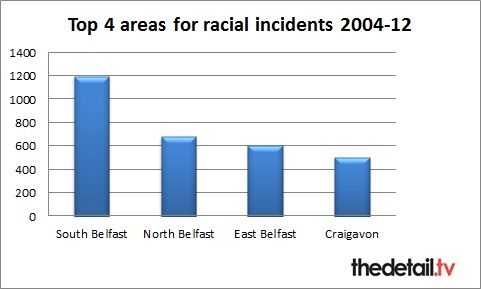

South Belfast had by far the largest ethnic minority population of Northern Ireland’s 18 constituencies, with over 4,000 people in 2003.

And loyalist districts in that part of the city were to be identified as hotspots for attacks.

One explanation was the availability of cheap rental accommodation in many loyalist areas, including those known as the Village, Sandy Row and Donegall Pass.

The once close-knit communities, ravaged by decades of violence and social deprivation, were portrayed as being traditionally suspicious of outsiders, and were identified as longstanding strongholds of loyalist paramilitarism.

Right wing groups including the National Front and Combat 18 had in the past been routinely linked to sections of loyalism, but 2003 also marked a period when such organisations sought to make political inroads in loyalist areas.

The White Nationalist Party (WNP) was among those that launched a leafleting campaign in loyalist communities, using racist propaganda that attacked the standing of ethnic minorities.

In October 2003 the Electoral Commission rejected an application by the WNP to stand for election, ruling that its title was likely to cause offence.

Right-wing organisations that heaped vitriol on immigrant communities were blamed for escalating tensions, as were loyalist paramilitaries who were to be implicated in orchestrating beatings and pipe bombings against minority groups.

Official reports, including by the Independent Monitoring Commission which studied the activities of terrorist groups, confirmed the role of paramilitaries in a string of attacks.

But some senior loyalist voices spoke out.

In January 2004 Nicem’s Patrick Yu issued a joint statement with David Ervine, the then leader of the Progressive Unionist Party (PUP), which is aligned to the loyalist paramilitary Ulster Volunteer Force (UVF).

The men condemned racist attacks and made a detailed series of recommendations to tackle such hate crime.

Within weeks, however, a disturbing new development took place when a leaflet was circulated around Donegall Pass in south Belfast.

The Chinese community was a prominent part of the local area but was targeted in the threatening propaganda sheet entitled “Yellow Invasion”.

It read: “I firmly believe that it is our duty to defend our community and our Protestant way of life within it. The influx of yellow people into Donegall Pass has done more damage than 35 years of the IRA’s recent campaign.”

The document listed Chinese businesses and added: “If a racist is someone who puts their own people, culture and heritage first…then we should be proud to be branded a racist.”

The Chief Constable Hugh Orde said the pamphlet was the work of loyalist paramilitaries.

The leaflet emerged against a background of attacks on families in the area and was widely condemned.

Anna Lo, who is now an elected representative at the Stormont Assembly, was then spokesperson for the Chinese Welfare Association and said that 60 Chinese families had once lived in the Donegall Pass area, though intimidation had seen that number drop to 23 out of the area’s 800 households

In April 2004 a fresh controversy erupted when loyalists objected to a modern new apartment complex in the nearby Sandy Row area of the city.

Another anonymous leaflet claimed the building was home to ethnic minorities, Catholics and “republican spies”.

Several hundred people marched on the site in a controversial demonstration which was widely criticised, despite claims by unionist representatives that tensions were being raised by a small minority.

Former residents of the complex recounted fleeing the area following the appearance of sectarian and racist graffiti.

The episode marked a further spike in news coverage that for a year had provided evidence of Northern Ireland’s growing problem of racist violence.

Groups such as Nicem warned, however, against a narrative that implied the issue was a problem confined only to loyalist areas and argued for a need to tackle racism across society, as well as battling issues such as deprivation which it said was among the underlying causes of such violence.

Nevertheless, loyalist paramilitaries were heavily implicated.

And in March 2005 the Loyalist Commission, a group representing a wide number of loyalist organisations, responded by launching a campaign which declared: “Loyalist or racist? You can’t be both.”

Loyalist leaders blamed the violence on small disaffected groups and publicly condemned their actions.

In a separate development, other political representatives were accused of sending confused messages.

They were warned that their efforts to explain concerns in their communities over the pace of change risked fuelling inaccurate perceptions of race issues.

The Alliance Party’s Naomi Long, who at the time sat on Belfast City Council warned: “There is a racist element manipulating the very real problem…[but]…it is not good enough for councillors to repeat propaganda – they need to challenge it. Problems of poverty and deprivation existed in Northern Ireland long before we had a large ethnic minority community, so let’s not make them scapegoats for our problems.”

Levels of racist attacks remained high and in 2009 the issue again resurfaced.

In March, Polish and Northern Ireland football fans clashed around a World Cup qualifier match, but there were subsequent attacks on migrant families living in south Belfast.

It is estimated that around 50-70 people, mostly Polish, were forced to leave their homes.

In June that year more than 100 Romanian people fled their homes in the south of the city after a spate of racist attacks that attracted international headlines.

The victims, made up of 20 families living in a small number of houses, were rushed to a church hall before further temporary accommodation was found in a leisure centre.

The images of terrified women clutching young children as they were bussed to safety caused widespread shock.

The attacks took place in loyalist areas but police denied an orchestrated campaign.

Nevertheless, the events were widely condemned, not only by political leaders in Northern Ireland, but by the then Prime Minister Gordon Brown who urged that all possible protection be given to the families.

A grim narrative had developed in Northern Ireland – the ebb and flow of the peace process was now regularly interspersed with high profile outbreaks of racist violence.

But what did it mean?

THE PEACE PROCESS – A TIME OF CHANGE AND UNCERTAINTYA report published by the University of Ulster in 1997 was billed as one of the first major research projects on Northern Ireland’s ethnic minorities and it found that “the relative size of all of them is increasing substantially”.

The study made a series of recommendations, including the need for clearer data to assess the needs of ethnic groups, but it also gauged their experience of violence.

Its survey found that 44% of individuals from minority groups experienced verbal abuse, while over half of Chinese people interviewed had suffered criminal damage to their property.

But at a time when much of society was optimistic about the potential of the emerging peace process, the report contained surprising views from within minority communities.

“The vast majority of respondents thought that things had changed in Northern Ireland since the paramilitary ceasefires of August 1994," it said.

“Half of those questioned felt that these ceasefires, and the consequent changes, will make things worse for their community.”

Police data recording hate crimes and less severe hate `incidents’, reveals that the trend of attacks continued to remain high throughout the last decade.

The figures for racist `incidents’ available from 1997-2012 shows the rising trend experienced over the last 15 years.

The sharp increase around 2004 is attributed to a change in how data was gathered, but could also signal a rise in cases as a result of the racist leafleting campaign in south Belfast during that period.

The upward trajectory for racist `incidents’ is also apparent in the police figures provided for recorded racist `crime’ – but there is some evidence of a levelling out of the numbers of cases.

Nicem notes, however that South Belfast bucks the trend where reported crime with a racist motivation peaked in 2008/09 with 131 cases, before dropping to 89 in 2010/11, only to rise again to 102 cases in 2011/12.

Additional statistical evidence is released in the latest edition of the Northern Ireland Peace Monitoring Report, which provides a detailed study of trends and developments in the peace process.

The document published by the Community Relations Council and written by Dr Paul Nolan notes “it is notoriously difficult to arrive at an accurate assessment of hate crime”.

It cites a 2012 report by the Home Office which cautioned that “research suggests that hate crime is hugely under-reported”, with victims fearful of reprisal attacks and doubtful of the ability of the authorities to take effective action.

Hate crime covers a range of offences in the UK including attacks with a racial motive, those targeting victims because of their sexual orientation, attacks on the disabled, transphobic and religious attacks. Northern Ireland includes a sixth category, sectarian hate crime, which involves not just a religious but also a political dimension.

Across the UK victims can now decide if a crime is to be recorded as a hate crime, with the police then responsible for registering the status, with evidence subsequently assessed by the Prosecution Service.

The Peace Monitoring report notes the power of high profile cases to shape opinion and raise concerns over hate crime.

But it adds that the “overall rates for hate crime have been diminishing over the past two years and in the past year there have been decreases within each of the six hate crime types”.

It details an overlap in hate crime – where for example attacks on the Polish community are recorded as racially motivated, even though police say at times the motive could be religious or sectarian.

The report records that the burning of Polish flags on loyalist bonfires in July 2012 “occurred in loyalist areas where part of the motivation for the attacks comes from the association of Polish people with Catholicism”.

Significantly, the report also asks if Northern Ireland has more hate crimes than other places.

It says the number of hate crimes in 2011-12 was 1,567, representing 3.3% of the total for England and Wales (47,748).

When measured against population size, Northern Ireland hate crime is above the average.

The proportion of crimes in England and Wales classed as hate crimes is 1.1%, but in Northern Ireland the proportion is higher at 1.4%.

But the report finds: “If however sectarianism is excluded, so that the measurement is in line with that used across the UK – only counting crimes linked to race, sexual orientation or disability – then the percentage in Northern Ireland is much lower: only 0.6% of all crimes in the region are in these categories.”

On the prosecution of hate crime, the Peace Monitoring report cites four critical reviews, including two from the Criminal Justice Inspectorate, a publication by the Institute for Conflict Research and a study commissioned by Nicem.

While the Criminal Justice (No 2) Order of 2004 allowed for tougher sentences where hate crimes were identified, figures from 2010 found only 13 cases where prosecutors brought the court’s attention to the “aggravated by hostility” motivation, and 11 cases where a judge had imposed an enhanced sentence.

Later figures for 2007-12 matched the trend identified for 2004-10, when “from the 13,655 incidents and 9,355 crimes reported to the PSNI only 12 successful prosecutions were reported for crimes aggravated by a hate factor”.

But the Monitoring Report says further examination and better data are required to track cases from their being reported as hate crimes by victims, to their passing through the various stages of the justice system.

It notes that of the 728 hate incidents dealt with in 2011, only 15% were treated as being `aggravated by hostility’ by the time they reached court.

But nevertheless in 86% of the cases a prosecution went ahead – but “without any hate motivation ascribed”.

The report highlights the inability of the justice system to currently provide a clear picture of the management of hate crime and says a better system must be established to determine where blockages occur.

But it adds: “In the meantime, the three reports mentioned above suggest that it is the criminal justice system itself which is in the dock.”

Nicem responds to the overview of hate crime figures, and the comparison with rates in Britain, by noting that the number of incidents reported to police does not represent the full picture.

Patrick Yu says: "I think the bigger point is that it is only the very small percentage of people who feel confident enough to report hate crime.

“So it doesn’t reflect the reality of the situation.

“I think all agencies agree that race hate crime, in particular the reporting of the crime, is only the tip of the iceberg."

He also says the tackling of racism has to be championed by government.

THE ROLE OF THE NORTHERN IRELAND ASSEMBLYThe Stormont administration led by the DUP and Sinn Féin has been criticised, including by Prime Minister David Cameron, for its failure to produce a blueprint for tackling sectarianism.

But Nicem notes that a strategy to combat racism is also gummed-up in the Stormont works, and has been for years.

The Racial Equality Strategy was stalled in 2007 when the Northern Ireland parties rejected the ‘Shared Future’ blueprint tabled by during a period of Direct Rule from London.

Stormont’s subsequent Cohesion, Sharing and Integration (CSI) Programme was heavily criticised by civic society and a replacement has yet to be agreed by the DUP and Sinn Féin.

Divisions between the two parties deepened as a result of the recent crisis over the restrictions placed on flying the Union flag at Belfast city hall and the outbreak of loyalist protests and violence.

In 2010 the Racial Equality Strategy was decoupled from the wider project to tackle sectarianism.

Stalled discussions involving a Racial Equality Panel recommenced in September 2012, and met again in December, with plans due for a further meeting in April.

But Nicem believes there is little evidence of it being prioritised by government.

In one of its many critiques, Nicem said: “The freezing of the Racial Equality Strategy and its accompanying departmental action plans has severely limited the realisation of rights of the black and minority ethnic communities in all areas of economic, social, political and cultural life.”

In a recent query, Nicem also asked the Office of First Minister and Deputy First Minister (OFMDFM) to detail the current timetable for updating the Race Relations (NI) Order 1997 to keep pace with advances in the law in Britain – a move which the Assembly agreed to review as far back as 2009.

The OFMDFM replied: “A potential programme of reform of our equality legislation is being considered within the Department. The Race Relations Order is part of this potential programme.

“We will also consult on possible legislative change as part of the consultation process on the new Racial Equality Strategy.”

The latest Census figures for Northern Ireland showed the Protestant community has dropped below 50% for the first time, sitting at 48% against the 45% of people from a Catholic background.

Northern Ireland no longer has a “majority community”.

Demographic trends suggest the gap between the traditional Orange and Green blocs is to narrow still further in the years ahead, meaning they are now effectively on a par.

The census revealed that 1.8% (32,400) of the Northern Ireland population belonged to minority ethnic groups in 2011, more than double the proportion in 2001 (0.8%).

Around 2% of the population is now made up of other European nationalities, with the largest proportion originally from Poland.

So how will Northern Ireland treat its ‘new minority’?

THE FUTUREGroups representing smaller communities in Northern Ireland have reached out to their neighbours, with joint campaigns, rallies, and shared cultural events to consolidate the predominantly positive relationships and help dismantle divisions where they exist.

Good work is being done to celebrate difference and build relationships.

But lobby groups believe political leaders must forge ahead to combat persistent prejudice.

In a report compiled by Nicem, its document opens with a quote from black civil rights champion, Martin Luther King: “Legislation cannot change hearts and minds, but it can stop the heartless.”

Fifteen years after the equality pledges made in the Good Friday Agreement, Patrick Yu says the future direction of the Stormont administration should be clear.

“Ethnic communities feel threatened at times of political upheaval,” he says.

“When larger groups in society become frustrated, it is not uncommon for them to look at ethnic minorities as an easy target.

“We want greater action.

“The government should protect ethnic minorities, in terms of the law, and policy.”

By

By