ULSTER loyalism is a rather curious beast. An ‘ism’ without a clear ideology, beyond allegiance to a British identity and more specifically to the Crown; a diversity of groups and organisations that have never developed a sense of being a ‘movement’, in the way that Irish republicanism has; a part of the wider unionist family but held at arm’s length from ‘respectable’ unionism, because of its willingness to take up arms for the cause; and a political entity without a clear electoral constituency.

Contemporary loyalism is a product of the sectarian divisions of Northern Ireland and the conflict, a response by people in working class communities to escalating disorder (although the UVF predates the actual beginning of the conflict), but which ultimately was acknowledged as an important component in the process of transition away from violence.

The declaration of ceasefire by the Combined Loyalist Military Command in October 1994 was soon followed by the formal participation of the two loyalist parties, the UVF-aligned Progressive Unionist Party and UDA-linked Ulster Democratic Party in the talks process, and which was legitimised through the election for the Northern Ireland Forum for Political Dialogue, in May 1996.

The period following the signing of the Agreement in April 1998 marked the highpoint of political loyalism, with David Ervine and Billy Hutchinson elected to the Northern Ireland Assembly. But by the time of Ervine’s death in 2007, loyalist electoral politics was already in decline. The UDP was dissolved in 2001 due to opposition to the Agreement among the UDA, while the PUP lost its last seat in the assembly in 2011, although it has retained seats on Belfast City and Causeway Coast and Glens Councils.

The challenge for political loyalism was that unionist voters never accepted the rationale of loyalist paramilitarism, and have always been reluctant to accept any attempt by erstwhile paramilitaries to transition into political representatives.

The collapse of the UDP in 2001 also highlighted the divisions within loyalism, and the opposition of many to the peace process and the political accommodation with Irish nationalism. Although many loyalists were committed to peacebuilding and working to that end within their communities, others were more concerned at the threats to the union and in particular to elements of loyalist popular culture.

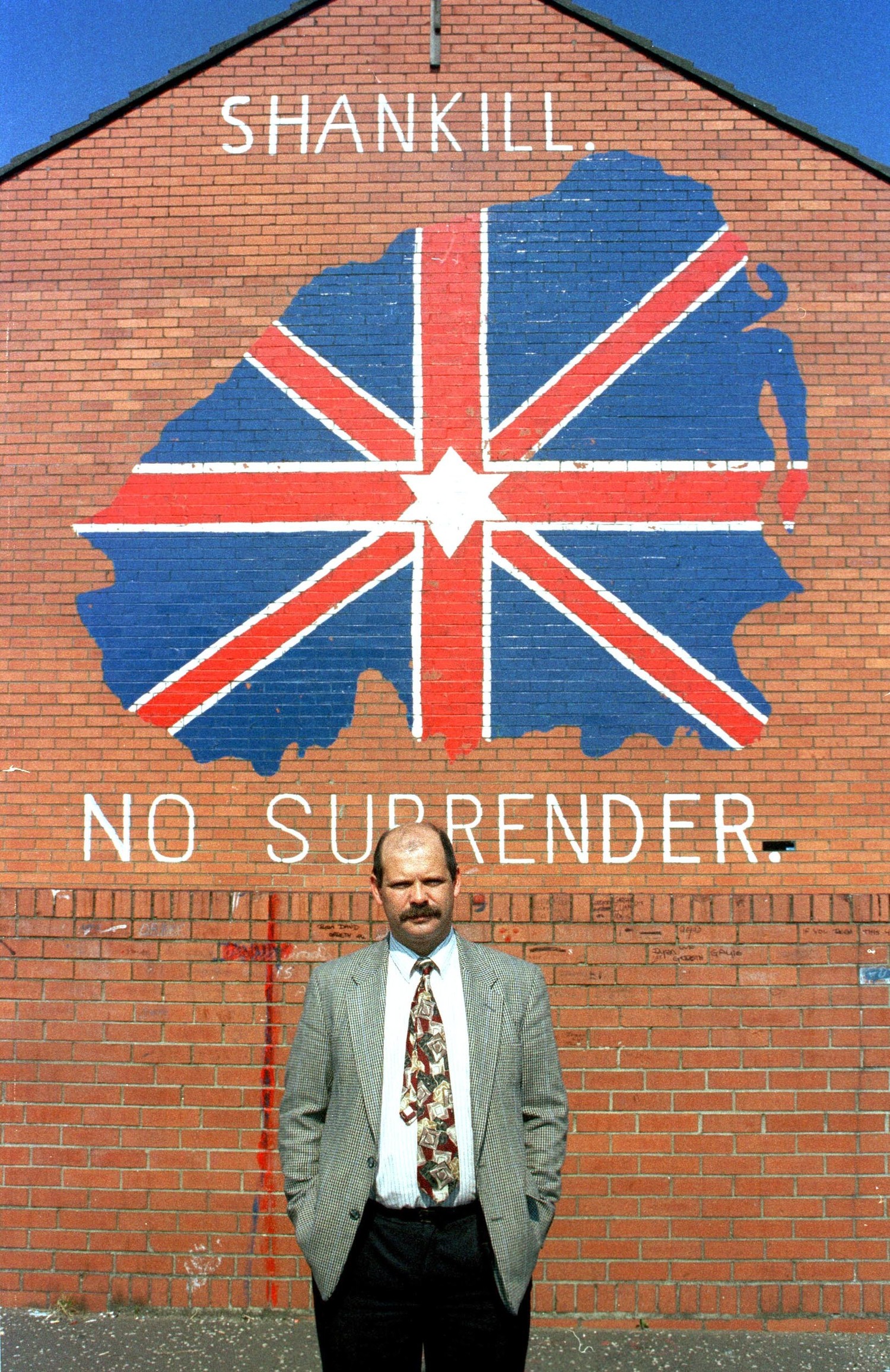

The commemorative parades of the loyal orders is largely viewed as a core component of the wider unionist culture, but the period of the conflict had seen significant changes to the rituals of the marching season and which came to the fore in the years after 1994. Loyalist ‘blood and thunder’ bands were visibly a core component of the ever prominent parades; loyalist flags and murals dominated Protestant working class areas; and the Eleventh night bonfires were opportunities for paramilitary ‘shows of strength’.

The disputes over parades that dominated the summer months from 1995 onwards mobilised loyalists to defend the perceived threats to their culture and provided a counterpoint to the political negotiations around the Agreement and the establishment of the new political and criminal justice institutions.

More recently the flag protests that began in late 2012 and the subsequent Twaddell peace camp protests against restrictions on the parade along the Crumlin Road both provided ammunition to the argument that loyalism was being targeted in a culture war, but defeat in both also highlighted the limited political capital of the loyalist working class.

Such mobilisations also highlighted the continuing presence of paramilitary loyalism. The Agreement included a reciprocal exchange of guns for prisoners but, after the prisoners were released, the focus was very much on securing the decommissioning of IRA weapons and demobilisation of military structures. Loyalist paramilitaries were regarded as less important as they were not considered as a security threat, nor seeking a role in government.

This has enabled paramilitary loyalism to retain, extend and consolidate its position in working class communities in Belfast and elsewhere through violence, threat and other forms of coercive control and criminal activities.

Twenty years after the Agreement, Ulster loyalism struggles to present a cogent sense of purpose. Political loyalism retains a foothold in the public sphere, but has not been publicly consulted in the negotiations to resolve the current impasse. Community loyalism has been instrumental in developing several innovative projects to deal with crime and anti-social behaviour. Cultural loyalism continues to defend their traditions, most recently through building ever bigger bonfires. But paramilitary loyalism looms large over all the other components and remains the publicly-defining element of Ulster loyalism.

- Dr Neil Jarman is a Research Fellow at the Senator George J Mitchell Institute for Global Peace, Security and Justice at Queen's University Belfast.

This article is published as part of a project by The Detail, with Queen's University Belfast, marking the 20th anniversary of the Belfast/Good Friday Agreement. The university will hold a major conference on April 10.