On Tuesday the biggest single supergrass trial in 25 years gets under way in Northern Ireland as the north Belfast loyalist Mark Haddock and 13 others go on trial on the word of two former comrades.

The Detail today examines the central role played by the state in the alleged activities of the Mount Vernon UVF over the past generation. And, below, we set out the questions raised by the reappearance of the supergrass for the justice system.

CRITICS brand it a charter for `paid perjurers’ while the PSNI and PPS insist it’s a vital tool in the justice system’s fight against paramilitaries and organised crime.

But why has the supergrass system been resurrected in 2011 and what impact will it have on the rule of law and order in Northern Ireland?

On Tuesday the single biggest supergrass trial in more than 25 years begins in court room No 12 of Laganside Courts, when 14 alleged UVF members go on trial in connection with the murder of UDA leader Tommy English in October 2000.

It will be the first time since 1985 that supergrasses have been used against a large number of suspected paramilitaries.

Crucially, as the alleged offences took place after 1998’s Good Friday Agreement, those standing in the dock could face life sentences behind bars, if convicted.

But the decision to resurrect the supergrass system has caused major controversy after its predecessor in the 1980s was severely discredited.

SUPERGRASS TRIALS OF 1980s END IN IGNOMINY

Between November 1981 and December 1985 an estimated 27 supergrasses agreed to testify against 600 republican and loyalist suspects.

In the first three supergrass trials (Bennett, Black and McGrady) nine out of ten defendants were found guilty on the word of the `reformed terrorists’.

Just under two-thirds of those who were found guilty were convicted without any supporting or corroborative evidence.

However the system fell apart less than two years later when Appeal Court judges refused to uphold convictions that had not been secured without corroborative evidence.

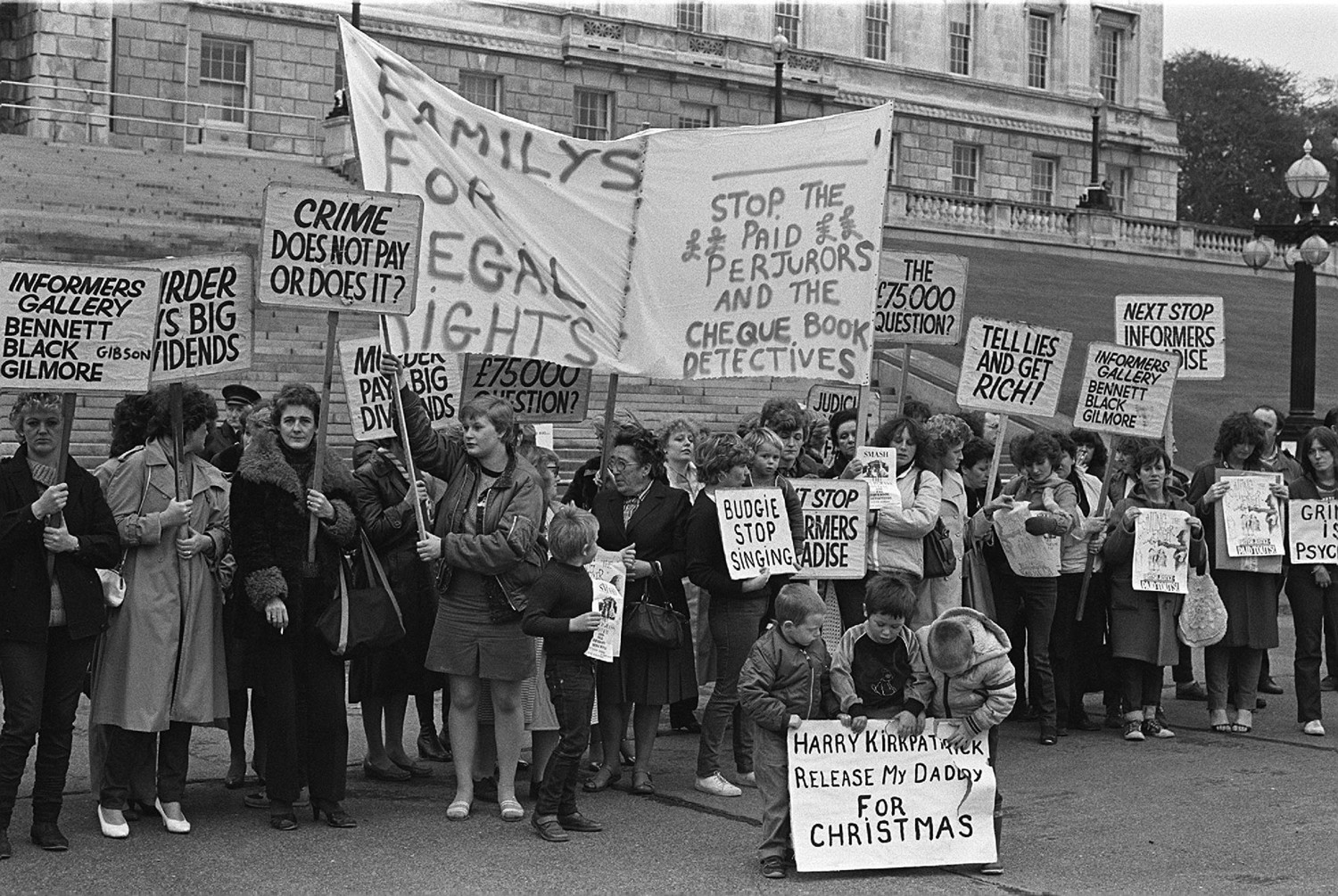

The last supergrass trial ended in December 1985 when the evidence of INLA man Harry Kirkpatrick saw 25 former associates sent to prison.

A year later 24 of those convictions were overturned on appeal.

Despite the collapse of trials and hundreds of paramilitary prisoners walking free, the original supergrasses still benefited from immunity from prosecution and a new identity on a witness protection scheme.

The public embarrassment to the state led to the supergrass system remaining dormant for 25 years.

Few, if any could have predicted its re-introduction in recent years.

RETURN OF THE SUPERGRASS SYSTEM CAUSES ANGER

However the introduction of the Serious Organised Crime and Police Act (SOCPA) in 2005 saw the unexpected revival of supergrass trials.

Under SOCPA, an accused could agree to turn supergrass, referred to as an “assisting offender”, and give evidence against former associates.

Unlike the previous system, the accused is not granted immunity, but instead is guaranteed a significantly reduced sentence.

This means a supergrass may be sentenced to life imprisonment but spend only three years in prison once a judge has taken into account that he has testified against former associates.

In the 1980s it was reported that supergrasses were offered hundreds of thousands of pounds in exchange for giving evidence.

However prosecutors insist that any defendant who turns `queens evidence’ in 2011 is barred from receiving any financial reward.

The Court of Appeal in Britain ruled that while the offer of a reduced sentence was the only incentive that could be offered to new supergrasses it was ``a price worth paying to achieve the overwhelming and recurring public interest that major criminals, in particular, should be caught and prosecuted to conviction".

Another crucial change in the law affecting those facing supergrass trials is the removal of the right to silence during police interview.

In the 1980s many suspects chose to remain silent during questioning, but the law now states that a judge can take an adverse inference on a defendant’s decision to remain silent during questioning.

It is speculated that this could emerge as a corroborative factor against some or all of the accused in the UVF murder trial.

2009 MURDER TRIAL SET PRECEDENT FOR SUPERGRASS CASES

In April 2009 a legal precedent was set for the Crown to bring a prosecution where a key witness could normally have expected to have been in the dock.

In that case mid-Ulster loyalist Steven Brown, also known as Steven Revels, was convicted of the brutal murder of Portadown teenagers David McIlwaine and Andrew Robb in Tandragee in February 2000.

Brown was sentenced to 30 years in prison after his former associate Mark Burcombe agreed to testify against him.

Crucially, unlike the previous 1980s cases, Brown lost his appeal against being convicted on the word of a supergrass.

Legal experts predict the Brown conviction will set the tone for what could unfold in this week’s court case.

BROTHERS TURN SUPERGRASS AGAINST UVF

In March 2010 Newtownabbey brothers David and Robert Stewart were sentenced to 22 years in prison for a series of UVF attacks.

However, because the Stewart brothers had agreed to turn supergrass against 14 former UVF associates, their sentences were reduced by three-quarters.

With time served on remand they were eligible for release this summer.

It is not known whether they are still in prison or have been placed on a witness protection scheme.

Crucially, the judge who convicted the Stewarts, Mr Justice Hart, warned them that if they failed to stick to the agreement to give evidence against their former UVF associates, they would face re-sentence, which could see them serving the minimum of 22 years.

Under the previous system, supergrasses faced no threat of prosecution even if they retracted their evidence at the eleventh hour.

The UVF murder trial is being seen as a legal landmark for the PSNI and PPS, with the real possibility of more supergrass trials if it succeeds in securing convictions.

The decision of former UVF brigadier Gary Haggarty to also turn supergrass against senior loyalists, is potentially explosive; within loyalist circles there is fervent speculation that Haggarty could give evidence against senior UVF figures going right back to include those who had previously stood trial in the supergrass trials of the 1980s.

Security sources last night hinted that there may even have to be a glass partition erected in the dock to seperate Mark Haddock, who has been exposed as having been a Special Branch agent, from his 13 co-accused.

VETERAN HUMAN RIGHTS LAWYER RECALLS MISTAKES OF THE PAST

But, in practical terms, can a system, which collapsed in ignominy 25 years ago, really be resurrected and what safeguards have been put in place to ensure that the mistakes of the 1980s are not repeated?

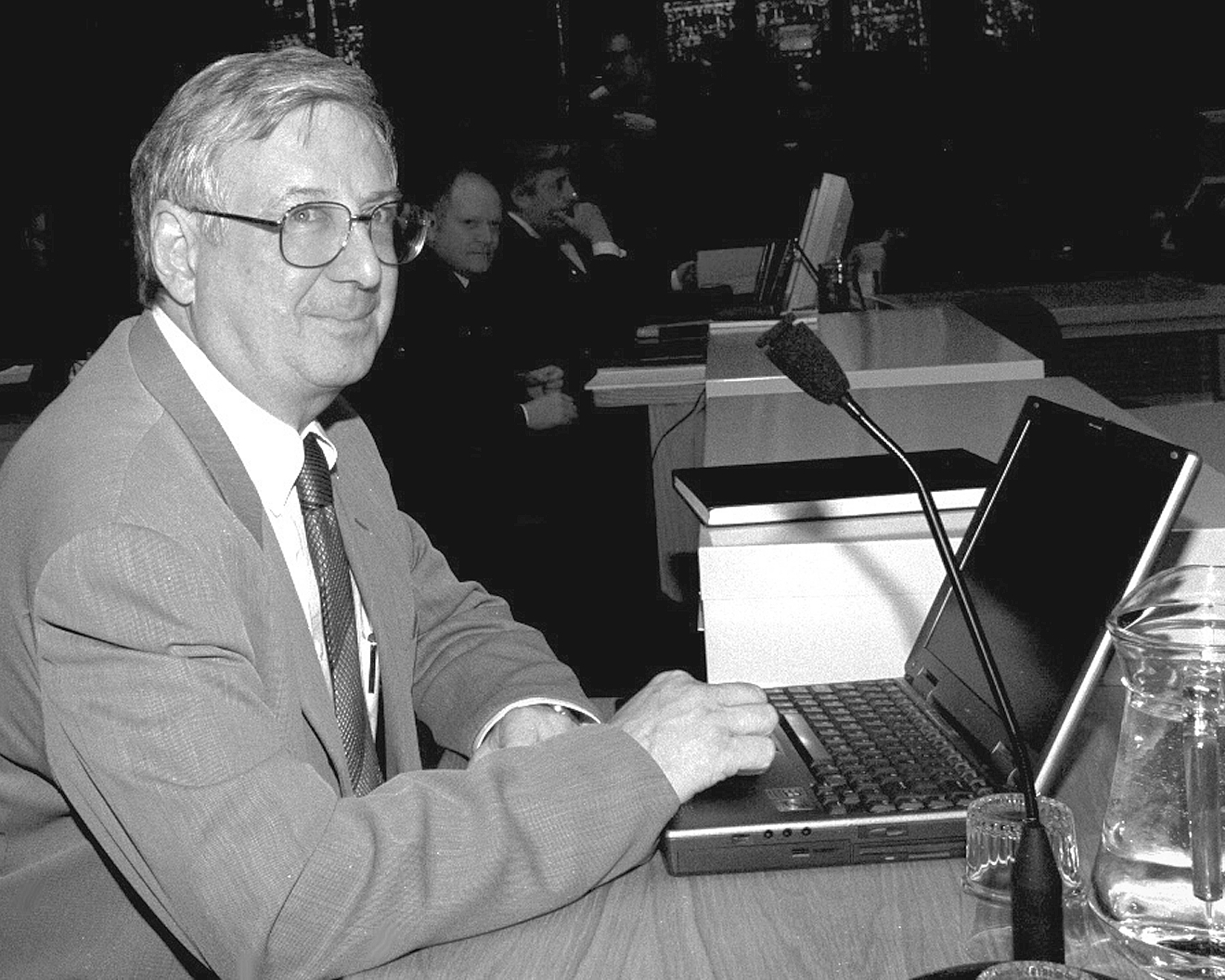

Lord Anthony Gifford QC is one of the most respected barristers in the British legal system having represented the Guilford Four, Birmingham Six and Bloody Sunday families.

In 1983 he spent a week in Northern Ireland interviewing lawyers, defendants, police and judges involved in the supergrass trials.

Lord Gifford later wrote a withering report of the supergrass system, which is widely credited as having played a significant role in the collapse of the system.

Recalling the shock at what he found in Northern Ireland in November 1983, he said:

“I found an extremely disturbing phenomenon going on.

“On a regular basis, people who were arrested and possibly had served a sentence before and didn’t want to serve another one, were offered the opportunity either of a light sentence or a complete amnesty and a new identity in exchange for giving evidence for the Crown.

“There was clear evidence this was being done in an extremely systematic and unjust way.

“The danger is that once the witness has agreed to turn `Queen’s evidence’ he or she can be coached and is coached.

“The question is whether they are giving evidence in accordance with what they genuinely recollect or in accordance with what the police want them to support.

“It was being used to get convictions against people who the police felt to be `guilty’.”

Lord Gifford said he had no doubt the supergrass system of the 1980s saw many abuses of due process.

“It was clear not only lawyers but the judiciary, in particular then Lord Chief Justice Lord Lowry, was very unhappy about it.

“That emerged in a number of appellant (appeal) cases in which supergrass verdicts were overturned.

“Hundreds of people were put on trial and convicted in this way, sometimes 20 and 30 at a time.

“In the cases which were most disturbing there was absolutely no corroborative evidence to support the conviction.

“Because there was no corroborative evidence the word of the informer/supergrass was relied on and, if he appeared to be giving evidence in a credible manner, then it was accepted.

“It’s a lottery, maybe some of the people were guilty, but you couldn’t say that, just because a supergrass said so.”

Recalling his hectic drives across the north visiting the families of those implicated by supergrasses, he said:

“I went back and forth across the divide and often found myself driving to places like Derry and other parts at all times of the day and night.

“I met all sorts of families and organisations, the nationalist Relatives for Justice (RFJ) and the loyalist Families for Legal Rights (FFLR).

“They both of course had the same experiences and the same agonies, but of course they couldn’t come together because they came from separate divides.”

SUPERGRASS FORETOLD FINUCANE SMEARS BY RUC

Lord Gifford’s enquiries also uncovered that the RUC had solicitor Pat Finucane in its sights as far back as 1983 and that an attempt was made to frame him and four other defence solicitors on the word of a supergrass.

This was more than five years before Mr Finucane was murdered in Northern Ireland’s most notorious case of collusion between the police and paramilitary agents.

On the last day of his visit, Gifford finally secured an interview with a supergrass, the west Belfast republican Robert Lean, who had turned supergrass against 23 IRA suspects weeks before.

Lean later publicly withdrew his evidence after escaping from `protective’ custody.

Lean alleged that he was asked to sign statements that police had pre-written, including one statement which claimed that five named solicitors were supplying information to the PIRA.

Recalling how he had been forced to make a 14-hour round drive to visit Lean who was in hiding in Waterford, Lord Gifford said: “I left Belfast at 3 o’clock and got to Waterford at 10 o’clock that night.

“I talked to Lean until about 2 o’clock in the morning and drove straight back to Belfast to get my plane at breakfast.

“It was all in the line of duty.

“One of the things I remember is that Lean said the police had asked him to sign a statement implicating various solicitors.

“I remember him saying he was asked to put Pat Finucane at the top of that list.”

Pat Finucane was shot dead in February 1989. Just weeks earlier Conservative government minister, Douglas Hogg MP, used parliamentary privilege to claim that some solicitors were supplying information to the PIRA.

Recalling the Tory MP’s comments shortly before the solicitor’s 1989 murder, Lord Gifford said:

“I remember when Pat Finucane was killed, wondering if the `evidence’ that was shown to Douglas Hogg was the same thing they had tried to get Robert Lean to sign.

“You can see how dangerous it all was.”

SUPERGRASS LITE OR DEJA VU?

The use of supergrass trials in Britain is defended on the basis that the evidence will be heard before a jury.

In Northern Ireland all supergrass trials are held under the Diplock, non-jury system which could leave such trials here open to potential charges of human rights abuses.

University of Ulster law lecturer Mary O’Rawe has written extensively on the changes in policing in Northern Ireland since the Good Friday Agreement.

In an article in the Detail, she points to the introduction of stricter guidelines in recent years to ensure that the mistakes of the 1980s supergrass system are not repeated.

“Given (that) there now exists a clear statutory basis for the utilisation of evidence from alleged former associates and this in the context of the human rights protections ushered (in) by the 1998 Human Rights Act – the new, improved system might be categorised more in terms of supergrass-lite than déjà-vu.

“Safeguards and strictures are in place.

“Money is not to change hands (other than by way of what might be deemed necessary to afford full protection to those assisting the crown in dangerous and murky situations).

“Improved disclosure provisions should result in better access to information in terms of the context and history of any informant giving evidence for the crown.”

However she also cautions that only experience will tell whether the new supergrass system will now deliver justice in 2011.

“While new improved safeguards may be pointed to as the order of the day at a formal level, the extent to which the lessons of the previous incarnation of supergrass trials in Northern Ireland have been fully taken on board is open to debate.

“Many of the same concerns that stalked and ultimately resulted in the shelving of the use of such evidence in the early 1980s, still attend the current process.

“Questions as to reliability, motivation, the possibility of conviction without any further corroboration are all still begged as regards the new regime.”