THE peace process has left some communities behind and young people are again being drawn into violence and the politics of protest. In his continuing series on the legacy of the past, The Detail’s Steven McCaffery reports on two men who have already been down that road.

THE riot started during an Orange Order parade, and soon large parts of the city were up in smoke.

Politicians at Stormont had originally supported a ban on the contentious march, but then suddenly did a u-turn and insisted it go ahead.

But these events didn’t take place in 2012 or 2013.

The violence escalated until hundreds were injured and eight people were dead. Rioters destroyed 2,000 homes, mostly those of Catholic families.

But this eruption of sectarian strife did not take place in 1969.

The year was 1935 and Belfast was suffering one of the worst outbreaks of its age-old problem: sectarian violence.

Maggie Kelly was pregnant with her third child when she was chased from her home by a mob.

It was her unborn son’s first experience of violence, but not the last.

In extensive interviews carried out before his death in 2007, John Kelly recounted his involvement in the IRA throughout the 1950s and ’60s.

The Detail also interviewed Roy Garland, a unionist political activist in the 1960s, on how the mood hardened in unionism ahead of the flashpoint year of 1969.

‘OLD IRELAND WILL BE FREE, FROM THE CENTRE TO THE SEA…’

John Kelly was born into a family with a strong republican lineage – his parents’ generation was linked to the War of Independence, while he literally learned the romanticised songs of the 1798 United Irishmen rebellion on his grandmother’s knee.

The Kellys were prominent in the north Belfast community where they lived, but as he grew-up he became aware that their politics set them apart.

John Kelly said: "The Special Branch were watching, of course. They wanted to discourage other families from associating with you.

“I remember growing up, and you were knocking about with fellas, and their families’ homes would be raided.”

He said politics was discussed by his parents, but he never felt encouraged to take an active interest.

“In fact, when I joined the IRA my parents didn’t know.”

He joined in 1952, aged 16. His induction involved history lectures in the backroom of a safe house – a process that continued each week for three months.

“They wanted to be sure that people would last the course and weren’t just trying to get their hands on a gun.”

But the guns soon followed.

THE BORDER CAMPAIGN

The IRA had launched headline grabbing raids on military bases, and Sinn Féin was to score symbolically significant political victories on both sides of the border.

But as the IRA pondered the launch of a new campaign in the mid ‘50s, some of its own members, including Kelly, warned that while the North’s Catholic minority was unhappy with its position in the unionist-dominated State, there was no support for violence.

He began attending IRA training camps in the Wicklow mountains.

He was trained in weapons and explosives with IRA members such as Feargal O’Hanlon and Seán South, who were later killed in what the IRA called Operation Harvest, but which became known as the Border Campaign.

It began in mid-December 1956 with a flurry of attacks, focused mainly on targets close to the border, but it was met with a strong security response by the authorities in the north and in the south.

More than a dozen people were killed in the years that followed, and by the end of the erratic campaign in February 1962 the IRA was defeated. Its violence was seen by many to be pointless, though members claimed to have carried their ‘cause’ into a new generation.

But this was a barren period for armed republicanism. It had no popular support and no prospect of securing its political aims which appeared to belong to a bygone era and seemed to ignore modern realities.

GUESTS OF THE NATION

John Kelly’s armed involvement ended shortly after the beginning of the campaign when he was captured with other IRA members hiding out at an isolated farm building at Dunnamore, near Cookstown, amid freezing winter weather.

“I remember being dragged out into the field and stripped to our underpants, our hands behind our head, being made to kneel down, not knowing whether they were going to shoot you and being totally frozen.”

Belfast’s infamous Crumlin Road Gaol awaited him.

The prison, built in the 1840s, was a dark and forbidding place.

Inside its walls was a world where grim days were lived out between metal and stone.

John Kelly, then aged 20, was sentenced to eight years.

IMAGES OF CRUMLIN ROAD GAOL

“I was given a grey uniform. The cell was eight-by-six, with a curved roof. The window at the back had iron bars. There was a locker and a table and a bible. It was sparse. Grim.

“The smell was the outstanding thing – the constant stench of urine and faeces.”

He heard people “cracking up at night”. But he turned his mind to the outside: “When you are in prison you are always looking for opportunities to escape.”

He formed a plan with another IRA prisoner, Danny Donnelly from Co Tyrone.

Kelly had hacksaw blades smuggled in to the jail. The pair hoped to cut through the bars in his cell window, escape across the grounds and scale the perimeter wall, despite the presence of armed guards.

They planned to escape under the cover of the Christmas festivities.

‘O HOLY NIGHT…’

On the evening of December 26, 1960, with their plan already delayed, they decided to act.

They forced their way out of the cell window – emerging into a storm of sleet and snow – and headed for the perimeter, carrying a rope fashioned from strips of cloth and electrical flex.

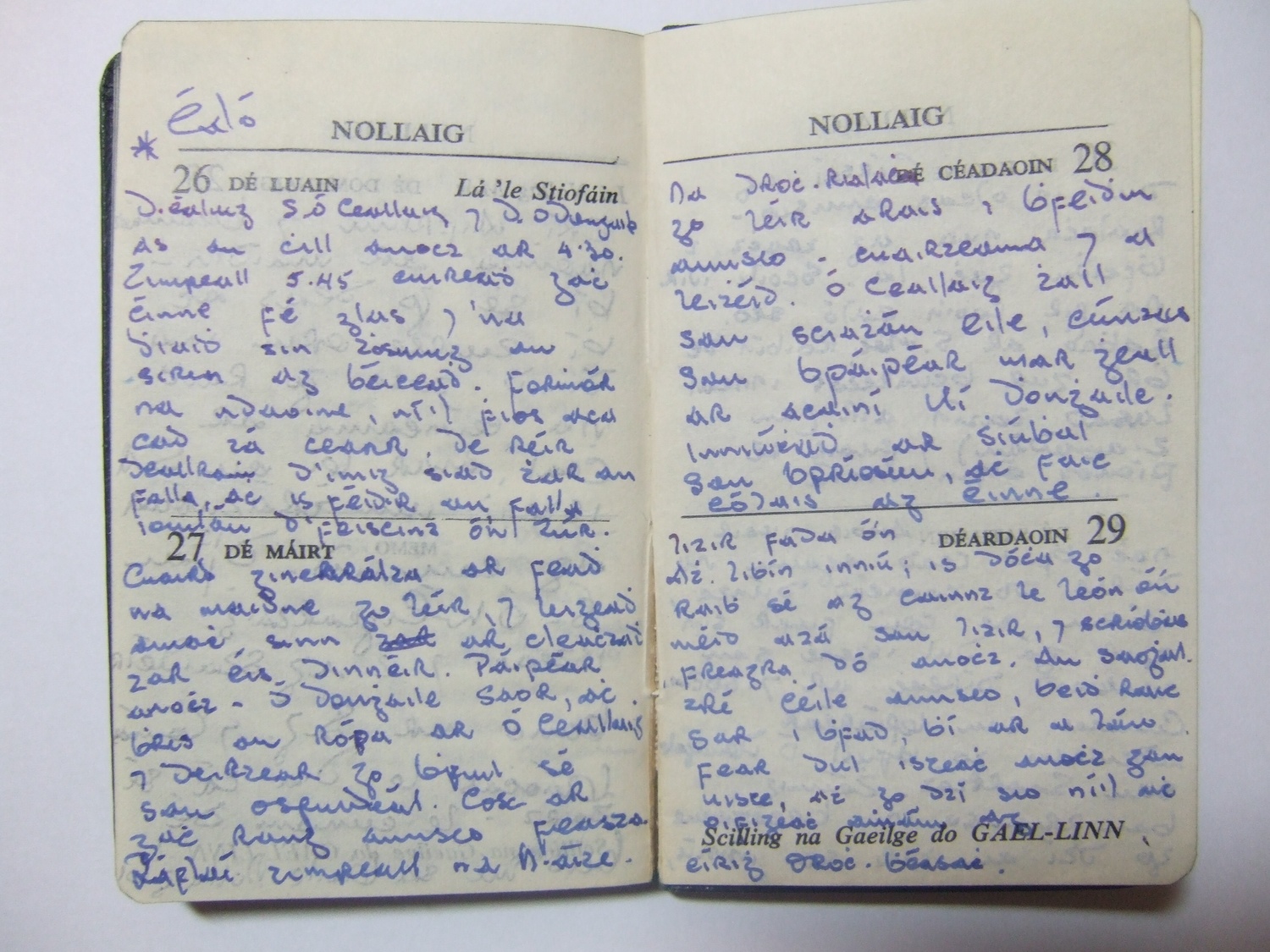

Inside the jail, another IRA inmate Eamonn Boyce had defied strict prison rules to keep a secret diary, which he wrote in Irish and kept hidden during his seven years in custody.

The diary, that surfaced decades later, recorded the escape: “John Kelly and Danny Donnelly escaped from the cells tonight at 4.30. At about 5.45 everyone was locked up and after that the siren began to scream. Most people don’t know what’s wrong. Apparently they went over the wall, but the whole wall is visible from the tower.”

The diary, published in the book The Insider, also revealed what happened next: “Danny Donnelly is free, but the rope broke on Kelly. Rumours all around.”

When the rope broke, Kelly landed on the inside of the prison wall. He was later hauled to a punishment cell where he lay, soaking wet and in agony. He was held in solitary confinement for a month and had six months added to his jail term.

Danny Donnelly suffered serious injuries in the drop to the outside, but he made it to the Kelly family home near the prison, and despite a massive manhunt, he escaped across the border. His book, Prisoner 1082, is dedicated to John Kelly.

Recalling the Crumlin Road break-out, Kelly said: “It was a failed escape attempt for me, but I was happy that one of us got away."

LIFE ON THE OUTSIDE

John Kelly said prison took its toll on everyone who experienced it. He was not afraid to spell out how the return to normal life in 1963 proved difficult.

He found he washed more frequently: "You were trying to wash the whole stink of the place off you.

“Also, I hated confinement, and used to walk the streets for hours at night to get out of the house.

“It took a long time to fit back into society. It was hard engaging with people.”

In time, this faded. He married, started a new life, and secured a good job.

But in 1969 he found himself again playing a high profile and controversial role in political events.

He was a defendant in the 1970 Arms Trial in Dublin, following allegations of an Irish government plot to import guns for nationalists in Northern Ireland.

He helped form the Provisional IRA at the opening of yet another violent phase of history.

When the Troubles effectively ended in 1998, with the signing of the Good Friday Agreement, he became an elected member of the power-sharing Assembly at Stormont.

He visited the Crumlin Road Gaol before his death in 2007 and stood again in his old cell.

He maintained his republican views, but refused to indulge in nostalgia about prison life.

“There is nothing nostalgic about it. Just bad memories.

“It was a prison. And prison is prison. It’s not a nice place to be.”

UNIONISM AT THE CROSSROADS – AGAIN

ROY Garland is known today as a liberal unionist commentator who argues for compromise and understanding between unionists and nationalists.

But in the 1960s he was a leading voice in the Young Unionists, and figured among those who opposed reforms being demanded by nationalists through vehicles like the Civil Rights movement.

“I remember one of the first meetings I had in the standing committee of the Unionist Party, as a Young Unionist delegate.

“I went right up to the front and (NI Prime Minister) Terence O’Neill was right in front of me….and I said `You are the destroyer of Ulster!’

“Cheers went up from hardliners at the back of the room.”

He came to unionism through membership of the Orange Order and said he and fellow protestors had a very “religiously orientated perspective”.

“The IRA – they were the foot soldiers of the Catholic Church – believe it or not. This is incredible now.

“Moscow was involved and Rome was involved and they were out to destroy everything we believed in – we were going to be destroyed.”

Sections of unionism feared a `doomsday’ and saw the need to “keep the pot boiling” so as to be ready for the supposed catastrophe to come.

When street demonstrations led to violence he felt that “loyalists or unionists had helped stimulate the riots, but blamed them on the IRA”.

It became a self-fulfilling prophesy: “Those riots confirmed what we were told ’There’s trouble coming…’.”

FEAR FACTOR

He wrote the biography of loyalist Gusty Spence, who re-formed the paramilitary UVF in the mid-’60s on the back of similar dire warnings.

Spence’s gang killed three people in 1966 in attacks that hinted at the sectarian bloodshed to come, but he later came to question violence and helped inspire loyalism’s role in the peace talks that led to the Good Friday Agreement of 1998.

Looking back at the ’60s, Roy Garland, recalled two infamous protests led by Ian Paisley over the flying of the Irish Tricolour in a republican office in west Belfast, and over a decision to lower the Union flag at Belfast City Hall due to the death of the Pope.

“People were taken with this thing that we are being sold out…..and flags were again central to it.”

When the violence of 1969 erupted, nationalists from Northern Ireland demanded help from Dublin.

The Taoiseach Jack Lynch gave what became a famous TV address, declaring his government could no longer “stand by”, and he spoke of Irish reunification as the longterm solution to the island’s political woes.

Lynch was said to be paying lip service to unity, which was not a political priority, to placate hardliners in his own party.

In the heat of ’69 such nuances were lost on northern nationalists, and on unionists.

Roy Garland said of Lynch’s famous speech: "This confirmed what we were being told: the Irish government, not just the IRA, were involved in a plot to destabilise Northern Ireland, to destroy Northern Ireland.

“And people became absolutely determined to fight this in anyway they could.”

But the ‘angry Young Unionist’ began to question what he was being told. He came to see the calls for Civil Rights reform as reasonable, and viewed the growing opposition to change as being too extreme.

“That’s knowing what I know now – but at the time I didn’t, I was accepting the propaganda."

He added: "Of course, it just escalated and once it started, my understanding from many people on the republican and loyalist side, is it was tit for tat.

“And it was really a bitter sort of sectarian struggle going on, that most people don’t want to recognise.

“People want to say, ‘they’re responsible, republicans, they caused it’. Others want to say, ‘no it was unionists, they caused it’.

“Both of us caused it, in my view."

Today, young nationalists and unionists are being arrested in demonstrations for, and against, controversial parades.

Some are being drawn into street protests over the flying of the Union flag.

Others are taking part in the paramilitary activity of dissident republican and loyalist groups – despite there being no support for such violence.

But we have been here before.

This society has a habit of allowing history to repeat itself.

See also: The Irish government and the Troubles

By

By