By Steven McCaffery

A top US political adviser who played a key role in launching the peace process has said it could take a further generation for it to truly take root and heal divisions in Northern Ireland.

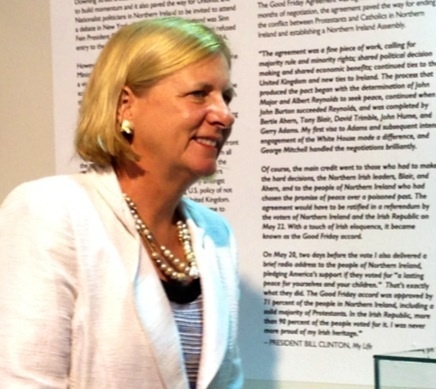

Nancy Soderberg was President Bill Clinton’s expert on Irish politics during his first term in the White House in the early 1990s when his intervention helped bring the decades of violence to an end.

The former presidential adviser said international experience showed her that it takes two generations for a peace process to work fully – with Northern Ireland now halfway through the process, having delivered an “irreversible” end to violence but still striving to remove historic sectarian divisions.

She is officially opening an exhibition on the President’s role in the peace process at the Clinton Centre in Enniskillen, which is built on the site of the 1987 Remembrance Sunday bombing when the IRA killed 11 people in a horrific attack which itself fuelled demands for an end to the Troubles.

“I do not believe the peace process is reversible at this stage. And that is the big story. The violence has stopped,” she said.

“You have isolated unfortunate incidents but largely you have a devolved government up and running, you have the police force which used to be eight per cent Catholic, is now 30 per cent Catholic – so it is moving forward. It is dramatically different.”

She added however: “But I think it is painfully slow.”

This comes as others have questioned the failure so far of the power-sharing government at Stormont to tackle the sectarian divide, despite the recent launch of a strategy on building a shared future unveiled by the DUP and Sinn Féin.

Ms Soderberg said: "I have watched this for many years now and tend to find that the parties make it very, very difficult, more difficult than it should be, but they eventually get there.

“That’s the key story here. I would like to see more progress here. I would like to see the peace walls in Belfast gone. I would like to see more integration, less division, and the walls of bigotry disappearing, they still exist.

“As generations go on – it usually takes two generations, having worked around the world in peace processes – it takes one generation to get the institutions and the ideas moving, and then another one to really get the bigotry out of your heart.

“And so you are in the first generation.

“It takes a long time.

“I think the leaders that are in charge now lived through it and have raw experience where they both feel that they are victims – and they both were victims.

“They both bear responsibility for that victimhood but it’s there and it’s real.

“And so there is a nervousness about moving too quickly, that will take one more generation I think before – it will never completely disappear – but it will be less raw and less visible.”

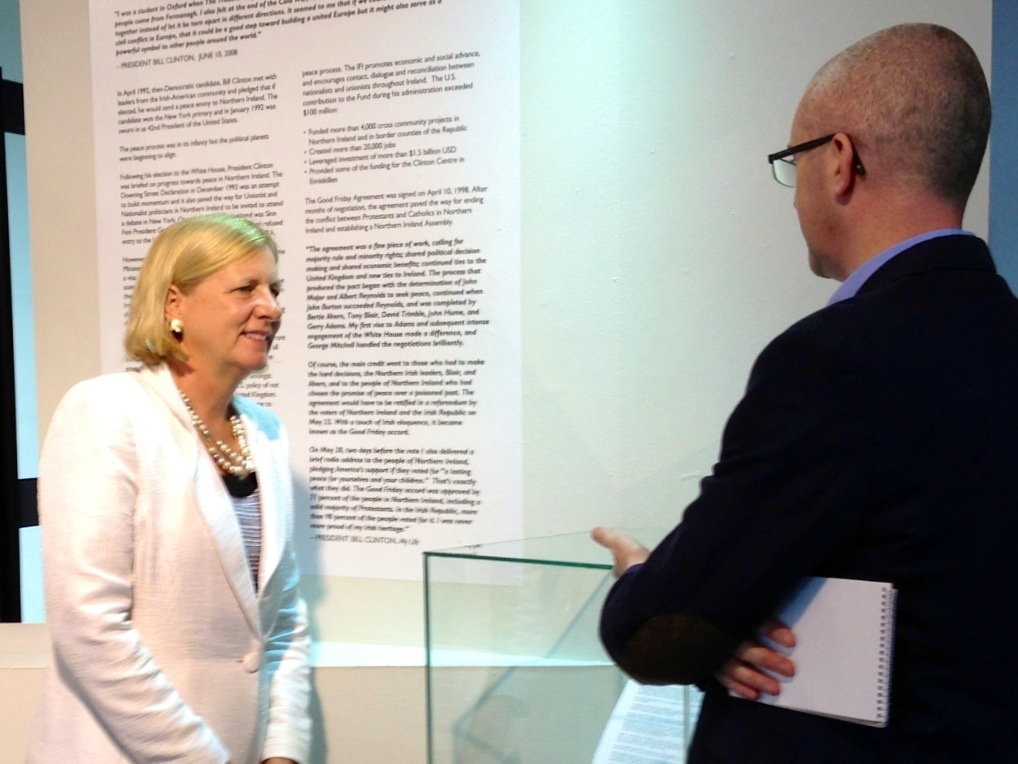

Top US adviser Nancy Soderberg with The Detail's Steven McCaffery in the Clinton centre, Enniskillen.

A former US ambassador to the United Nations, her career began as an adviser to Ted Kennedy, a role which ensured she knew the key players in the Northern Ireland political scene. She sat on Bill Clinton’s National Security Council and became his senior adviser on Ireland.

She cites the Downing Street Declaration of December 1993, when the British and Irish governments mapped out their view of a path out of violence and political deadlock, as the moment when President Clinton saw his opportunity to get fully involved.

But a decision to offer Gerry Adams a visa in 1994 caused serious political tensions between Washington and London.

On entering the Clinton exhibition for the first time, Ms Soderberg was shocked to see a briefing note she had written for White House staff to explain their decision to issue the visa – a decision which she said not only divided the President and the Prime Minister, but also split the US administration where many believed the IRA was not serious about the promise of a ceasefire.

Pointing at the display case in the Clinton centre, she said: “Wait a minute, I wrote those! I remember these!”

She recalled the furore following the visa decision, which allowed Mr Adams to attend an Irish American event in the US while the IRA was still involved in violence, but which came amid hopes a ceasefire was close.

“It was difficult,” Ms Soderberg recalled.

“He [Gerry Adams] hadn’t gone quite as far as we had hoped and the consul general who had interviewed him said he didn’t unequivocally renounce violence – but we found some silver lining in the words that enabled us to move forward.”

She said of the White House notes, which acted as a guide for government representatives explaining their position: “Those were very carefully crafted talking points. I spent hours on those.”

In the document, Mr Adams is said to have affirmed “his desire to see an end to all violence”.

The former White House adviser said of the notes: "I think we sent them to the State Department to read, but I’m not sure they did.

“John Major didn’t take our call for a week.

“Those were very heady times.”

She said her contacts with Irish America and insights from John Hume – a leader that she said had never fully secured the praise he deserves for his pivotal role – led her to offer advice to the President that went against the “status quo” inside US government circles where she said the British view of the political situation held sway.

Britain was telling the US that “nothing was happening” within Irish republicanism, but she added “they were just flat wrong”.

But President Clinton was keen to find a way into the situation in a bid to boost the search for peace.

“The entire rest of the government, except for Jean Kennedy Smith, ambassador to Ireland, was against it, but the White House saw the possibilities,” she said.

“I still remember people from the State Department, the FBI, and the Justice Department yelling at me saying `How could you do that?’.”

She said it was hoped a ceasefire would follow the visa row which erupted in January 1994.

“By July I was beginning to think we had been snookered, but then in late August it [the ceasefire] happened.”

The former presidential aide, who is still an influential political strategist in the US, praised the role of all those who helped deliver the peace process, but said the exhibition is a testament to the work of President Clinton and his determination to play a positive role in ending the Troubles.

“Walking in here just makes me feel very proud to have been part of that effort and to have worked for a man who really helped so many lives here.

“Before he got involved there were 200-300 people a year dying and those people are walking around alive today – they don’t know who they are – but you know they are there.

“That’s a very powerful feeling.”

She insisted she believed the US remained ready to be directly involved in the continuing peace process.

“Oh yes, absolutely. The Americans will be there whenever they are needed.”

She said it was appropriate that today the key role go to the local parties, though a “little push” from America could occasionally help.

Ms Soderberg said she believed it was very important, and very useful for economic development, that the G8 was being held in Fermanagh this week and could showcase the success of the peace process.

But looking back, the moment when she believed peace was a possibility came when President Clinton and his wife Hillary visited Belfast in Christmas 1995, where they were greeted by thousands at city hall.

“That’s when we knew it was going to last – out in front of city hall, with Van Morrison playing.

‘You could just feel it. People came out in droves. They were voting with their feet – saying, `enough, stop it’ – you could just feel it.

“It was the most extraordinary night of my career in the White House.

“There were lots of bumps on the road. The ceasefire fell apart months later, but got put back together again and really it has held ever since.

“But that’s honestly when I knew. I looked out at that crowd – I actually walked around the crowd and just watched people and it was really powerful.

“That’s when I knew.”

International students from trouble spots around the world are attending a summer school at the Clinton centre in Enniskillen, which Ms Soderberg welcomed as a further legacy of the Clinton era and which she said was a powerful tool to help spread the success of the peace process overseas.

She said that the international world took hope from the success of Northern Ireland’s journey.

“What you find in peace processes around the world [is that] anyone who has gone through a divided society, particularly with violence, feels that their situation is unique.

“And I have seen this many times, where you bring people in and they hear about what the Irish went through and they say, `wait a minute, that’s exactly what we had happen’.

“And so you realise you’re part of a human trend, not a local trend, and it gives you courage that others have done it.”

© The Detail 2013

By

By