CAMPAIGNERS in favour of voting to leave the European Union in Thursday’s referendum deny that it’s a risky move – they call such claims ‘Project Fear’.

The Leave campaign is instead arguing that if UK citizens vote to go it alone, they’ll have a better life outside the EU.

That might be true, but voters can’t be sure.

And there are a number of reasons why that element of risk could be an issue for Northern Ireland unionists in particular.

LIVING IN INTERESTING TIMES

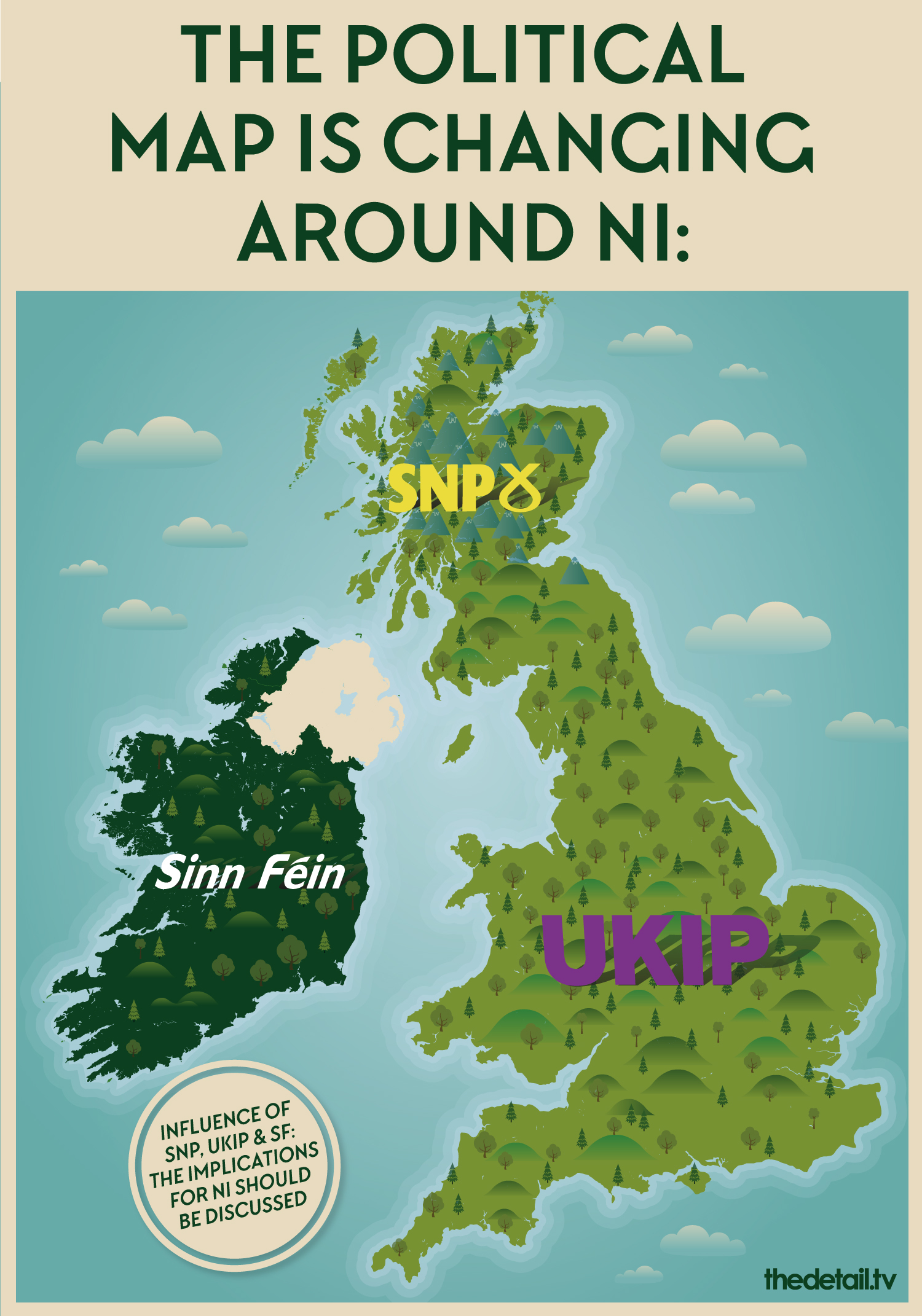

In April 2015 The Detail launched an infographic project, here, that looked at a series of major political issues.

One of the images reflected how politics was in a state of flux across Britain and Ireland: Sinn Féin had emerged as a mainstream party in the Irish republic, the Scottish referendum on independence had boosted the SNP (Scottish National Party), and UKIP (UK Independence Party) was pushing English sentiment towards a poll on EU membership.

The problem was that the implications for Northern Ireland were not being discussed.

So what happened since that cautionary image was published?

Scotland had chosen to remain in the UK in the 2014 independence referendum, but 45% of voters were ready to make the leap. The pro-independence SNP subsequently made landslide gains in the general election of May 2015 and the aftershock is still being felt, with speculation that Scotland may object if the UK votes to leave the EU.

In the Republic of Ireland, Sinn Féin made further incremental gains in the Dáil, which is now the party’s centre of gravity.

As The Detail previously reported here, that means Northern Ireland’s government is now being jointly run by a Dublin-led political party.

Meanwhile, the emotions stoked by UKIP eventually forced David Cameron’s hand, resulting in this week’s historic referendum.

As a result of all of this, Northern Ireland already faces the pressure of political developments in Dublin and Edinburgh.

A vote to leave the EU could also see unforeseen changes rippling out from London.

THE ECONOMY

The economic arguments around the UK referendum have produced a slew of contradictory statistics, but one unavoidable reality is that Northern Ireland faces challenges that do not exist for voters elsewhere.

The Detail reported here how Northern Ireland farmers rely on the EU for 87% of their annual income.

The wider Northern Ireland economy is also weak in UK terms: it is too dependent on the public sector, has had higher levels of unemployment, higher levels of long-term unemployment, while a fifth of the population is estimated to live in relative poverty.

While the issue of immigration has gripped the referendum debate in England, often in terms that have sparked controversy, Northern Ireland has experienced very low levels of immigration.

Despite the Stormont Assembly's delay of almost ten years in introducing a racial equality strategy for Northern Ireland, there is widespread political recognition for the positive contribution made by newcomer communities from Europe and beyond.

And it is worth remembering that Irish nationalist and unionist communities each have strong emigration histories.

So, while immigration questions risk being overstated, a more substantial issue is the potential hardening of the border with the Irish republic.

The Irish Association, which discusses cultural, economic and social relations on the island of Ireland, commissioned a report on cross-border issues for a conference held in May at the Corrymeela peace and reconciliation centre in Co Antrim.

The report wasn’t aimed at the referendum, but two statistics illustrated the importance of the border as an area of opportunity, but also as an area where communities require support rather than potential disruption.

It showed that since 1991 the EU’s Interreg programme brought approximately 1.13billion euros to Northern Ireland and the border region.

On travel, it found that 14 million cars cross the border annually on the road between Dundalk and Newry, which is the main Dublin-Belfast corridor.

Life on the border is more fluid than ever.

Future economic progress for Northern Ireland could depend on maximising cross-border opportunities to save public money and boost industry.

UNIONIST POLITICS

Against this background, while Irish nationalist parties support the EU link, there are mixed signals coming from unionist politicians.

The DUP is clearly calling for the UK to leave the EU.

But, given the financial concerns in sectors such as farming, is everyone in the party really convinced by the calls to "take our country back" from Europe?

The party would deny any soft-peddling on the referendum.

But its campaign has been dominated by Sammy Wilson, one of the DUP old guard, while its new generation of leaders appeared to play a more muted role.

The Ulster Unionists favour remaining in the EU, but in an open letter to The News Letter party veterans argued in favour of getting out and said: “At present Europe blocks us from having free trade with our former colonies who gave freely of their armies in two world wars, and other conflicts, to protect the United Kingdom.”

The signatories, who included former leader Lord Trimble, expressed hopes for a “British renaissance of global proportions”.

But does that sound like an appeal to unionist heads or to unionist hearts?

‘UNKNOWN UNKNOWNS’

Former US Defence Secretary Donald Rumsfeld won a “Foot in Mouth” award for his unforgettable warning that: "There are known knowns; there are things we know we know. We also know there are known unknowns, that is to say, we know there are some things we do not know, but there are also unknown unknowns, the ones we don’t know we don’t know....”

He would have slotted perfectly into the chaotic debate we’ve seen on the EU referendum.

There has been a failure to break through the noise.

Slogans around sovereignty and immigration have made the headlines in England.

But should Northern Ireland unionists pause before taking a step that would inevitably create further uncertainty?

Unionists are often told that the constitutional question is settled, that Irish nationalism is satisfied, and that Scotland is quietened.

But, in reality, all these factors remain live political issues.

Unionism is in a strong position in Northern Ireland, but it could face challenges in the future that require confidence and sure-footedness.

Would leaving the EU introduce an extra element of uncertainty at a time when unionism needs to build stability?

By

By