WHEN it emerged that the deal to save Stormont was called 'A Fresh Start', not everyone realised the title applied to Peter Robinson too.

The announcement of his retirement – coming just 48 hours after the new agreement – accounts for some of the recent events that have proven so confusing for his party’s followers.

Why had the DUP embraced a fresh deal with Sinn Féin, despite new revelations about the IRA? Why the chaos of rotating DUP ministers to ensure the wobbling Assembly remained upright?

It’s clear the DUP believed it had to salvage the devolved government – unionism’s sole powerbase – but the party also needed to provide its new leadership with breathing space ahead of May’s Assembly election.

There were many agendas at play during Stormont’s recent negotiations, but it’s now obvious that the timing of the deal was closely aligned to Peter Robinson’s exit strategy.

Despite facing challenges inside and outside his party, and while battling ill health, the 66-year-old leader has succeeded in leaving under what are probably the best circumstances he could have mustered.

DON’T LOOK BACK IN ANGER

His departure is the end of an era.

Peter Robinson does not carry the historic notoriety of his predecessor Ian Paisley, but he has been a prominent political player since the outbreak of the Troubles and is a huge figure in modern unionism.

His 40 year career, however, drags a lot of baggage behind it: there are the images of the steely figure standing for decades beside a bellowing Paisley, there was the politician who briefly donned the red beret of Ulster Resistance, and the protestor who infamously ‘invaded’ the Monaghan village of Clontibret.

But there is another Peter Robinson.

In the aftermath of the 1985 Anglo-Irish Agreement, which dealt a body blow to unionism by handing the Irish government a formal role in Northern Ireland affairs for the first time, he nevertheless secretly worked with members of the Ulster Unionist Party to draw up the ‘Task Force Report’ calling for a strategic rethink of unionist politics.

The endeavour was rejected by the leaders of the two parties, during a frenetic period that damaged the tense Paisley/Robinson relationship.

However, when political compromise did arrive in 1998 through the Good Friday Agreement, Robinson helped lead his party’s bitter opposition to the power-sharing agreement and he was key to the agitation that led to the overthrow of the dominant Ulster Unionists.

By 2007 the DUP had engineered a deal that saw Ian Paisley finally take on a full government role with Sinn Féin, though there was a belief that Peter Robinson was the power behind the throne.

He was credited with creating the DUP roadmap and effectively positioning Paisley to do the deal with republicans, even though latterly the Paisleys insisted it was the 'Big Man' who was the real history-maker.

The landmark agreement between the DUP and Sinn Féin, bringing together two such implacable enemies, marked a political highpoint.

But putting the unlikely partnership into practice proved very difficult.

Life between the two parties wasn’t as rosy under Ian Paisley’s term as is often claimed.

While it has also emerged that the Paisley/Robinson relationship soured behind the scenes, there were major tensions between the DUP and republicans.

Despite the apparent warmth built up between First Minister Paisley and deputy First Minister Martin McGuinness, which saw them dubbed the ‘Chuckle Brothers’, it’s forgotten that during the same period the DUP took delight in blocking every Sinn Féin initiative at Stormont.

That friction surfaced dramatically when the DUP ousted its founder and installed his longstanding deputy into the top job.

Sinn Féin immediately put Peter Robinson under pressure to make good on the promise to devolve policing and justice powers from Westminster to Stormont.

The DUP resisted, until events forced the party’s hand.

IRIS ROBINSON SCANDAL

No one would have blamed Peter Robinson for walking away from politics five years ago when scandal engulfed his family and his party.

The revelations that his wife, herself a high profile politician at the time, had an affair with a teenager and helped secure money from property developers to set him up in business, brought political calamity on her husband’s career.

It also arguably put his party on the back-foot during subsequent crisis negotiations over the future of the Assembly. The talks held at a snowbound Hillsborough Castle in Co Down, saw the DUP finally agree to devolving law and order powers to Stormont.

Political tension heightened around Peter Robinson again within months, as the DUP leader lost the East Belfast Westminster seat he had held for over 30 years.

There were fresh predictions that he would have to resign, but somehow he kept going. He had asked for space for his family and requested privacy around his wife’s battle with mental ill health.

Against all the odds the 2011 Assembly elections saw an upturn in his political fortunes and delivered an historic victory for the DUP. The party took 38 seats in Stormont’s 108 seat chamber, representing a high watermark his successors will struggle to match.

Even then, when others thought he might leave the stage, he stayed on and claimed his work was not yet done.

THE ‘NEW NORTHERN IRELANDERS’

In November 2012, with the new DUP leader facing into his 64th birthday, there was speculation once again that he might stand aside.

But in his keynote speech to his party’s annual conference he sketched out a longer-term plan.

At a time when republicans were demanding a border poll to kick-start a debate on Irish reunification, Robinson insisted that large numbers of Catholics were already debating a long-term future in a reformed Northern Ireland – if only the DUP’s hardline base could stomach further compromises to seal the deal.

The sprawling conference room of the La Mon hotel outside Belfast was packed when he arrived to deliver his address – with more than half of the 17-page text dedicated to repeating the same message:

“In this decade I believe we have been presented with unionism’s greatest opportunity. And this time our purpose is not to defeat, but, by words and deeds, to persuade....That means challenging ourselves….it means building a society where everyone feels equally valued….we must look outward beyond our normal horizons.”

The speech was widely reported as a repeat of a unionist belief that Catholics could be persuaded to vote for the DUP. Others saw it as a mere positioning of the party to attract moderate unionist voters.

But his true message may have been more challenging than that.

The party knew that the findings of the latest census were to be released and it was expected to effectively chart the continuing decline of unionism’s majority in Northern Ireland.

His speech wasn’t a hollow prediction that somehow nationalists could be converted into unionists. Sources indicated at the time that it was instead the beginning of a challenge to his party rank and file that fresh concessions would have to be made to nationalists, but that the prize could be their permanent acquiescence to maintaining the Union.

THE FLAGS CRISIS

His speech at the 2012 DUP conference was missing one key element.

In the drafting of the text, advisers included a line that explained ‘you don’t have to wave a flag to be a unionist’.

But at that time the DUP was investing substantial political capital in a row at Belfast City Hall, where nationalists were demanding the lowering of the Union flag, which at that stage flew every day of the year over the domed building.

A Belfast City Council vote on restricting the flag’s appearances to designated days was imminent and so the ‘flag waving’ line was dropped from Peter Robinson’s speech.

Unionists at city hall had distributed tens of thousands of leaflets attacking the cross-community Alliance Party in anticipation that it was set to support the compromise of restricting the flying of the UK flag.

Peter Robinson’s enemies detected a desire to damage the Alliance Party, which had so spectacularly seized his East Belfast parliamentary seat.

The DUP denied any link, but what was undeniable was that unionism lost control of the outburst of loyalist anger and violence that followed the decision to restrict the flag.

The violence that emerged from months of flag protests caused chaos across Northern Ireland, saw attacks on police, and led to the repeated targeting of Alliance politicians.

Stormont was again in crisis, as the international community responded to media images of an unstable Northern Ireland.

The British and Irish governments, who were supposed to be driving the peace process, were caught asleep at the wheel.

But the chaos also crashed any DUP plans to adopt a new liberal stance to appeal to what some in the party termed the ‘new Northern Irelanders’ - those moderate unionists and nationalists who were at peace with the political status quo and who could trump the demographic shifts that risked weakening unionism’s hand.

The DUP was forced instead to embark on protracted efforts to soothe the concerns of its traditional political support base.

The accusation is that a short term tactic to retake East Belfast backfired on unionism’s long-term interests.

Over the years, Peter Robinson had become embroiled in other controversies.

At a time when politicians' wages were under the spotlight, his family's combined political earnings were highlighted, and they were dubbed the 'Swish family Robinson'.

There was negative publicity over a land deal involving a £5 transaction with a developer, where the DUP leader insisted the episode was completely legitimate and he accused critics of trying to falsely smear him.

Controversial remarks made while he defended a pastor who had called Islam 'heathen', led to a public apology in what was a PR disaster.

Peter Robinson's party craved an end to such publicity.

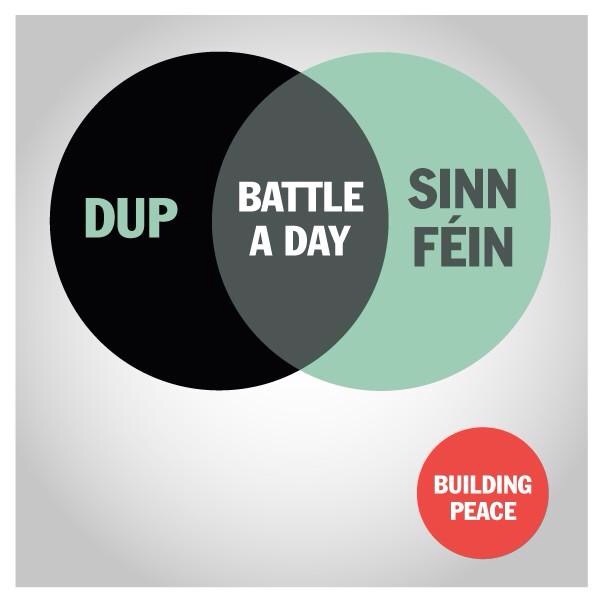

A poster campaign by The Detail reflected how political deadlock was failing to reflect an increasingly diverse society

THE SEARCH FOR STABILITY

The flag crisis had exposed the disinterest of the British and Irish governments in the peace process and set off alarm bells about the future.

Talks chaired by US diplomat Richard Haass tackled issues such as the legacy of the Troubles and sought to bring a new stability to Stormont politics, but the emerging deal failed to get sufficient support from the parties or the British government.

It was believed – rightly or wrongly – that the number of DUP MPs gave it a bargaining power over the Conservatives at Westminster and had undermined the agreement.

A further round of talks last year led to what was called the Stormont House deal. That agreement was effectively brought down by Sinn Féin, who may have hoped a looming Westminster election could see the Tories ousted and allow an opportunity to press any new British government for a better financial package.

In the end, voters returned a Conservative majority. Prime Minister David Cameron didn’t need the DUP and he had strengthened his hand over Sinn Féin.

The politicians returned to the talks table again to deliver the latest accord, which they unconvincingly entitled ‘A Fresh Start’.

It came against the background of strong public disquiet over Stormont's poor record and complaints that the administration was failing to legislate for an increasingly diverse society.

The run-up to the talks was littered with incident.

In May Peter Robinson suffered a suspected heart attack and was hospitalised for treatment.

The summer months saw IRA members linked to murder.

And after Nama, the Republic’s state-owned ‘bad bank’, announced the sale of its entire Northern Ireland portfolio for over £1billion, there were subsequent allegations of a plan to make payments to a politician. This led Peter Robinson to publicly deny any connection to the claims which he rejected out of hand.

As the latest talks to save Stormont got under way, he had emerged from his period of hospitalisation and recuperation to somehow push on once more, but at obvious physical cost.

A NEW ERA

Peter Robinson has led unionism on a rollercoaster ride, but now that he is set to jump off, what is around the next bend for his party?

The DUP is entering uncharted territory.

The party is losing its chief decision-maker, the man colleagues said they often looked to as "the smartest guy in the room".

If, as expected, Nigel Dodds is installed as leader he will do so from Westminster.

If Arlene Foster is installed as First Minister she will head an Assembly team which in the past has required the Robinson authority to hold its internal divisions in check.

Peter Robinson has battled through physical ailment, etched on his face over recent months, to stabilise Stormont. He has held off an early election and provided his party with an opportunity to steady itself ahead of the Assembly poll.

The ‘Fresh Start’ deal gives Stormont the political space and the money to see out the next four years.

But the DUP will face substantial challenges.

Despite the clear denials of any wrong-doing by Peter Robinson in the Nama affair, the publicity and official inquiries into the matter will continue after his resignation.

The toxic issue of parading is unresolved and its violent nexus is in Nigel Dodds’ North Belfast constituency.

Politicians have to return to the loaded issue of the legacy of the Troubles and chart a way out of that mire.

Unionism faces increased calls from nationalists for their Irish identity to be given equal standing in the public space, against the background of demographic shifts that are already having a political impact.

Life at the Assembly will bring challenges for the new DUP leaders, who must also keep one eye on the growth of Sinn Féin in the Republic.

Does unionism have a long-term strategy to deal with these challenges?

Peter Robinson helped take his party into government with their enemy and the sceptics have found that the sky didn’t fall in. He will say he has brought the DUP to the strongest possible political position.

But despite his achievements, he has left a lot of unfinished business.

His political legacy will depend on what the DUP does next.

Can the new leadership learn from his mistakes as well as his successes?

By

By