AS the Stormont negotiations move up a gear, a string of tense political contests are playing out. Steven McCaffery reports.

HARDLINE unionist Jim Allister claims the DUP spends so much time looking over its shoulder at him, the party has a ‘crick in its neck’.

He might be right. The 75,806 votes he won in the recent European election appear to have spooked Peter Robinson’s party.

So too has the performance of the Ulster Unionists in the local government elections, the re-emergence of the loyalist PUP, and the signs of support for UKIP which got 24,584 first preference votes in the Euro poll.

The DUP is looking over its shoulder at various opponents – some who pose a real threat and others who are cluttering the field as the party seeks to corral unionism to its advantage.

But the DUP is not alone.

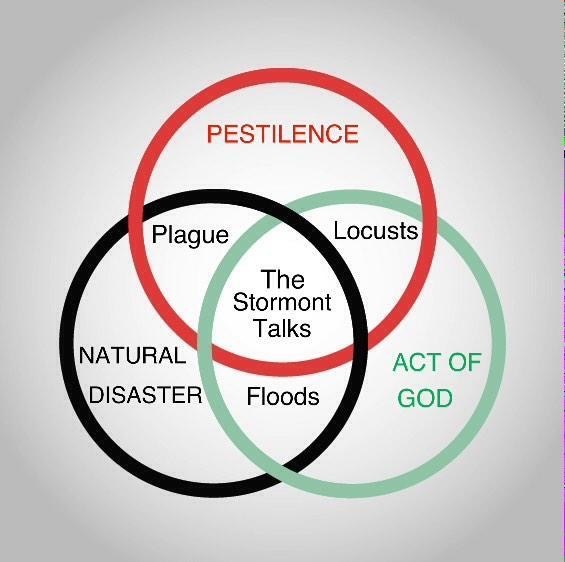

A quick glance around the unhappy faces gathered at the talks table for the Stormont negotiations reveals a remarkable collection of competing agendas.

For example, while the DUP faces pressures, it also has powerful cards it can play.

It knows that the lead partner in the British government, the Conservative Party, fears it may need the support of Democratic Unionist MPs at Westminster if the Tories fall short of an overall majority in next May’s General Election.

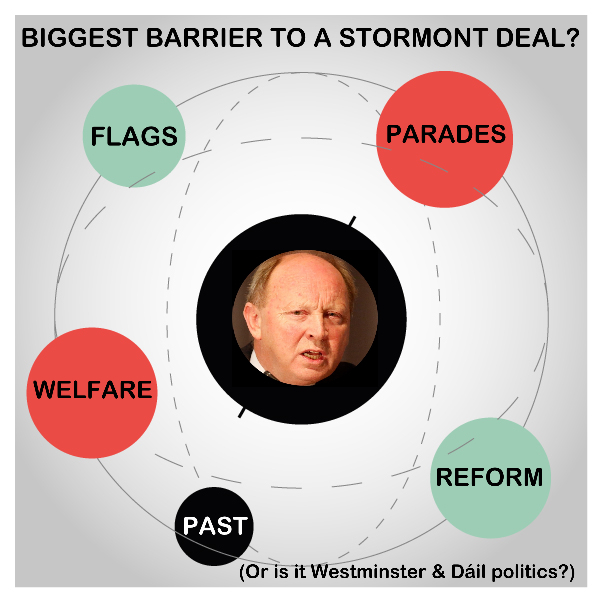

In fact, there are those who believe that the reason the Haass talks of last year failed to deliver agreement on flags, parades and dealing with the legacy of the Troubles, was because of a common approach by the DUP and the British government.

While this is denied by both the Conservatives and the Democratic Unionists, it is noticeable that the Haass agenda has been pushed to the periphery of the latest round of negotiations at Stormont.

So far, the public debate around the current talks has focused on economic matters, to the exclusion of other issues.

That is underlined by Chancellor George Osborne’s new offer to devolve Corporation Tax to Northern Ireland, but on the condition that the Stormont parties first tie themselves to other financial agreements inside the negotiations.

At the opposite end of the talks table, however, you find that the Irish government has its own fish to fry.

Sinn Féin has become a prominent party in the Dáil and is riding high in opinion polls in the Republic.

Over recent days, while it was barely reported north of the border, the government parties in Dublin launched a full frontal attack on Sinn Féin.

In a noted change of tack, Taoiseach Enda Kenny led the charge, in what was seen as a drawing of battle lines ahead of the south’s General Election due within the next 18 months.

“The situation is becoming much clearer, the divide in Irish society,” the Taoiseach said. "The choice will be a Fine Gael-led government or a group possibly led by Sinn Féin.”

Mr Kenny’s salvo was followed by others from his Minister for Finance Michael Noonan, plus the Tánaiste and Labour leader Joan Burton.

The government was seen to be sending a series of messages to a southern electorate that has been jolted into open revolt over the prospect of water charges after years of austerity measures.

Is it irrelevant to the Stormont talks that Sinn Féin is an arch enemy of the Republic’s governing parties?

And while the Stormont negotiations are so peripheral to the Dublin political scene as to be off the map, some observers do wonder if the northern talks could play out in a way which might damage Sinn Féin in the south.

Since the talks began, however, the Irish government has underlined its commitment to playing a fair and constructive role.

Sinn Féin, meanwhile, has its own agenda.

The rivalry between it and the other parties in the south cuts both ways.

There is no doubt that any potential deal at Stormont, or any risk of the institutions collapsing, will be judged against a number of factors by republicans.

But the impact on Sinn Féin’s fortunes south of the border will be a key consideration.

The peace process has always had political competition at its heart and the politics of either Westminster or the Dáil have interrupted progress in the past. But at key moments there has usually been enough common ground to ensure agreement.

However, for years there has been severe criticism of the downward trajectory of Stormont politics and of the stewardship of the two sovereign governments.

Now the Conservatives, the DUP, Fine Gael, Labour and Sinn Féin – who are all major participants in the talks – could potentially have party political considerations preying on their minds.

They will all point to their bona fides and their track record of having repeatedly stretched themselves in the search for peace and reconciliation.

But sceptics might wonder if the political process born out of the Good Friday Agreement has ever faced such a potentially corrosive collection of competing agendas?

By

By