RESEARCHERS have studied the impact of the crisis that shook Northern Ireland politics two years ago when Belfast City Hall voted to restrict the flying of the Union flag. Here, writing for The Detail, one of the authors of the new report charts the episode’s continuing significance.

By Paul NolanON Saturday 30 November a sad little drama played itself out in Belfast city centre.

There was to have been a mass rally to mark the second anniversary of the flag protest, and the organising group, called Loyal People’s Protest, had notified the Parades Commission that 6,000 people would take part. Concerned about the possible effect on Belfast traders, the Commission decided to restrict the number to 500 people.

The concern was misplaced: the days when flag protestors could command the streets are long gone. Only 200 turned up and their procession through the city centre went virtually unnoticed.

The heady sense that somehow, some way, the blocking of roads would see the Union flag back in front of the City Hall, has given way to a sense of disillusionment and hurt within the loyalist community.

A message posted on one of the main organising Facebook sites, Save Our Union Flag, in April this year expressed the mood: “Didn’t take long for the ulster people to give up.. What happened to standing together and fighting the fight.. SF/IRA are laughing at us!”.

That post appeared at the same time that we were beginning a research project into the flag protest. The ‘we’ in this case was a group of academics based at Queen’s University in Belfast who, from different disciplines, research this sort of cultural contestation: Pete Shirlow, Dominic Bryan, Katy Hayward and Clare Dwyer, together with Katy Radford from the Institute for Conflict Research and myself, an independent researcher.

The study involved interviews with approximately 60 people (and conversations with hundreds), a comprehensive trawl of print and broadcast media, an examination of social media, the extensive use of PSNI records, and the creation of a detailed database of all events during the period from December 2012 to March 2013. We have sifted both the qualitative and quantitative data in order to construct the analysis.

Why put so much effort into a study of this particular episode? In terms of the long-term trajectory of the peace process was it anything more than a bump in the road?

If you were simply counting numbers, then the flag protest was simply not on the same scale as previous expressions of unionist anger. Even in those areas where support was strongest, like east Belfast, the percentage of local people who took to the streets was much smaller than the percentage of people who didn’t – in fact the protestors were never even one per cent of the 90,000 population of east Belfast.

This was nothing like the protests in the 1985 against the Anglo-Irish Agreement; on that occasion it was not 2,000 people who gathered at the City Hall, but 200,000. Nor did the flag protest riots ever match against the intensity of the Drumcree demonstrations of the mid-1990s.

That said, for the months that it lasted, it was an extraordinarily tenacious expression of grievance.

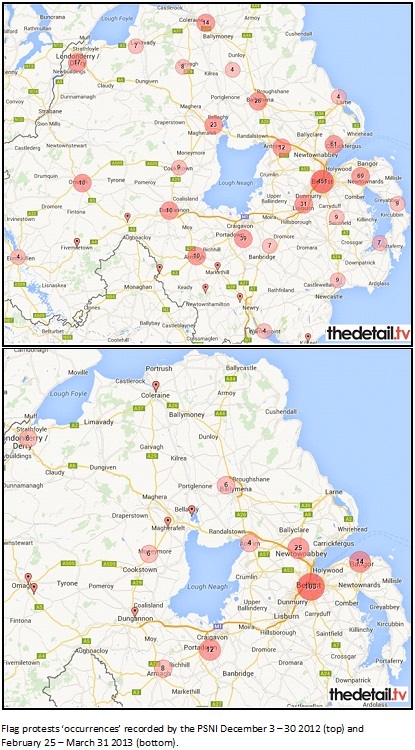

The PSNI recorded approximately 2,980 ‘occurrences’ related to the flags dispute and these may include a crime (or multiple crimes), an incident (i.e. anti-social behaviour or suspicious behaviour) or a report of information. The number of people recorded in relation to these occurrences peaked in the week 17-23 December 2012, when almost 10,000 people, at different places across Northern Ireland, were recorded as being involved in protests and related incidents.

The second peak came in mid-January 2013. On one particular night in that period there were 84 different sites of protest. Some people participated in multiple protests, and our interviewees included those who had been on 60 -70 protests.

If each individual ‘act of protest’ is counted as a separate event then there were 55,521 such acts in the period from 3 December 2012 to 17 March 2013.

What resulted? If the flag protest were to be judged in terms of its declared objective then it could be shown to have had zero success. The flagpole at Belfast City Hall remains bare for 347 days a year. The celebrity leaders have faded back into obscurity. Their electoral mettle was tested in the May 2014 elections when the ‘parties of the protest’, suffered meltdown – in fact, the meltdown occurred even before the elections took place. Willie Frazer’s Protestant Coalition fell apart almost instantly, while Jamie Bryson’s attempt to raise £5,000 to run as an independent ended when with revelation that he had only succeeded in raising £165.

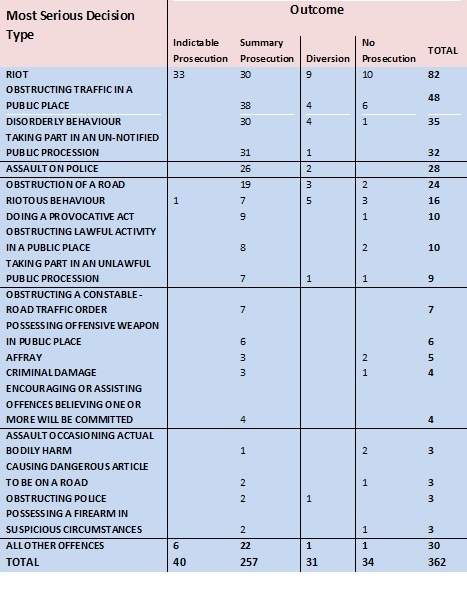

Meanwhile, the courts were processing those arrested during the protests: 411 people from the loyalist community have now passed through the criminal justice system. Only 37 have in fact received custodial sentences, but for those protestors who felt the heady rush of power at the height of the protest the experience has been a chastening one. One consequence was a relatively peaceful marching season in 2014.

And yet, despite it all – the low level of participation, the failure to get anywhere close to achieving its stated objective – the protest has a significance that is only now being understood.

Speaking on the 20th anniversary of the IRA ceasefire at the end of August this year, Martin McGuinness pinpointed this as the moment that the Northern Ireland peace process began its downward spiral.

In his presentation there is a simple cause-and-effect connection between the two. We do not accept that one was the cause of the other in quite this way. Certainly if the peace process could be plotted on a graph there is a slow gradient upward to December 2012, and then at 3 December, the night of the City hall vote, comes the point of inflection, after which the graph begins its descent.

It may be however that the flag protest was not itself the cause, but the expression – albeit a dramatic one – of a deeper malaise, and that even if hadn’t happened the gathering storm would have found some other way to earth itself. The fact that it was a flagpole which acted as the lightning rod acts on the symbolic level, but a thunderclap event was waiting to happen in any case.

Our study shows that the new weather system that entered at that point has had profound consequences for unionism – and, by extension, the body politic in Northern Ireland.

The scope for compromise was severely limited during the Haass/O’Sullivan talks, and as Richard Haass admitted in the early hours of New Year’s Day it was the issue of flags and emblems that turned out to be the most intractable of all.

Whether the new multi-party talks escape from its shadow remains to be seen. Two years on from the vote in the City Hall the effects of that decision rumble on.

The report will be available here. A print version will be launched by Queen’s University in January.

By

By