(L-R) Scott Jennings, Robert Millar, Tony Carmichael, Ellen Fearon and Ryan Harling from Belfast Student Housing Co-operative. Photo from Ryan Harling

Last spring, Ryan Harling found himself feeling “powerless and defeated” over student housing issues.

As students' union vice president at Ulster University’s Magee campus in Derry, he was “inundated” with requests for help with accommodation problems.

Although students have long faced challenges in obtaining affordable private and university-managed accommodation, Mr Harling said the problem has become more acute in recent years.

“High demand and low supply means that students are being milked dry as cash cows,” he said.

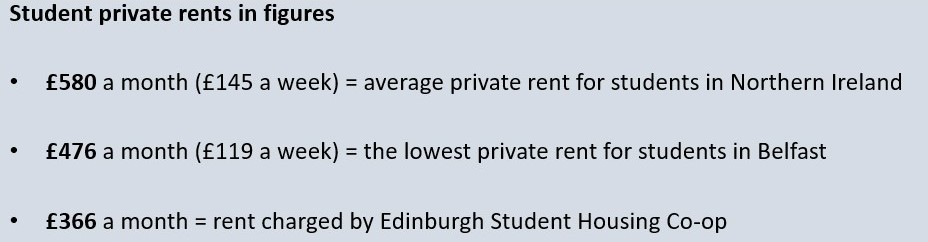

The most recent survey from the National Union of Students (NUS) shows that the average private rent for students in Northern Ireland is £145 a week.

Mr Harling said the lowest private rent for students in Belfast is £119 a week, amounting to £4,522 for a 38-week lease.

Students who are not means-tested can only receive a maximum loan of £4,840, meaning that 93% of their loan would go on rental costs.

Mr Harling said anecdotal evidence has suggested that a lack of student housing was exacerbated by the pandemic, when some landlords opted to change their properties into B&Bs or standard rentals.

“Student landlords over Covid decided that B&B markets etc are more reliable,” Mr Harling said.

He added: “Anecdotally, in Magee where the cohort of health and social care students are coming over from Jordanstown it’s been difficult to find accommodation for them.”

Mr Harling said students are so desperate, they are turning to temporary accommodation.

“I was talking to one international student (at Ulster University in Coleraine) who wasn’t able to find a property and is now living in a caravan for three months,” he said.

“This isn’t a new story... government has let us down. We are going through a cost-of-living crisis, there’s no Stormont, students are fed up.

“We now know it’s time for students as the people most affected by making a decision to take action because no one else will.”

Robert Millar, vice president of Ulster University Students’ Union in Belfast, said housing demand is hugely outstripping supply in the city.

He said although housing pressures have pre-dated Covid, the return of students to campuses following the pandemic, and the movement of thousands from Jordanstown to Ulster University’s new Belfast campus, has added to housing stress.

“All these different issues have added together to create this crisis, which could have been averted in the first place if there had been more affordable and better-quality accommodation provided,” he said.

A spokeswoman for Ulster University said higher education institutions across the UK are “experiencing high demand for student accommodation”.

She said not all students who apply for university-managed accommodation will secure it.

“UU is committed to meeting its accommodation guarantees for first year and international students who committed to the university by applying for accommodation by the designated deadline dates,” she said.

She added: “Collaboration with local private sector accommodation providers remains a priority to expand the options available to students.”

A spokesman from Queen’s University Belfast said it increased its number of rooms to almost 4,000 this year.

“This meant that all students who applied for Queen's accommodation this academic year have been offered a place,” he said.

The spokesman said some rooms are still available.

Belfast Student Housing Co-op

Disillusioned with the housing options available to students - both in private accommodation and university-run halls, Mr Harling began looking at possible alternatives, including co-operative housing.

Earlier this year, he and four others, including Mr Millar, officially set up a group which aims to establish the first student housing co-op in Northern Ireland.

In a co-operative, a group of people live together, each of whom take an equal role in managing the house.

Co-operative student housing has a long history in the US and parts of mainland Europe, but the UK only has four student co-ops – Edinburgh, Birmingham, Sheffield and Seasalt in Brighton - all established in the last decade.

“It’s not this crazy idea,” Mr Harling said.

“It’s a massive alternative – democratically-run accommodation.”

Co-ops charge much lower rents than private or university-run accommodation - £366 a month for a room in the Edinburgh building, compared to similar private rentals of up to £800 - because they are managed and generally maintained by the students themselves.

All four co-ops in Britain lease their buildings, either from a housing association or another co-op.

Mr Harling said his group has been looking at potential properties in and around Belfast and will be seeking investment to try and secure one.

“Students do care a lot about sustainability and the environment,” he said.

“When students are given the chance to take control of their surroundings, they really let that show.”

Tiziana O'Hara from Co-operative Alternatives with Scott Jennings, Robert Millar, Tony Carmichael, Ellen Fearon and Ryan Harling from Belfast Student Housing Co-operative. Photo from Ryan Harling

Co-ops in Northern Ireland

Tiziana O'Hara, a director at Belfast-based Co-operative Alternatives, said there has been a surge of interest in co-ops in recent years.

The body, which helps people set up co-ops, has advised the students.

Ms O’Hara said at least two attempts have been made to set up general housing co-ops in Northern Ireland but neither has so far been successful.

However, she said the success of student co-ops in Britain was heartening.

“It’s catching the opportunities that are available,” she said.

She added: “Let us explore a different level of ownership instead of keeping everything completely public but derelict or completely private.

“There is a middle ground. There could be some kind of shared ownership so we could see some kind of regeneration.

“Sometimes it’s about inspiring our local authorities to be looking at things a bit differently.”

She said some vacant properties in Belfast city centre might be suitable for students.

“Look at our city centre,” she said.

“It is not used by people, not because they don’t go shopping but because they don’t live there any more.

“Some of the beautiful buildings we have are not used. There are some public spaces that we haven’t developed with the people at the centre.”

Co-ops in Britain

Student co-ops in Britain vary greatly in size. Edinburgh has 106 members; Birmingham has nine; Brighton has seven, and Sheffield has five.

Mike Shaw, chair of Student Co-op Homes – the body which helps students set up co-ops, was one of the founders of Edinburgh’s Student Co-op which opened in 2014.

He said the wider establishment of co-ops could help ease the housing crisis for students.

“When you look at co-ops in the US, the one in Berkeley (the University of California) for example has over 1,000 members, it can work on many different scales,” he said.

Mr Shaw said setting up a co-op can be challenging but the financial benefits for students are clear.

“It’s not easy,” he said.

“You get a group of students together and you can get incorporated to be set up as a legal body.

“Then it’s a case of trying to secure a property, which is really difficult.

“So far we haven’t had a student co-op that’s been directly able to borrow enough money to buy a property.

“The first three co-ops that got set up – Edinburgh, Birmingham and Sheffield – they lease houses from supportive organisations.”

Edinburgh student co-op

Edinburgh - the largest student co-op in Britain - is oversubscribed and has a waiting list of 80 people.

The co-op, in former student halls close to Edinburgh Napier University, has more than 100 single rooms spread over 24 flats.

Students are charged £366 per room, including energy bills, internet, soap and other basic supplies.

Sonny Scott, a Napier student and secretary of Edinburgh Student Housing Co-op, said it charges members “what we feel is going to cover all the costs”.

“We made a rent increase in September from £338 a month (to £366),” he said.

At the start of October, the Scottish Parliament introduced emergency legislation to freeze most rents until the end of March next year.

Mr Scott said the co-op, like all householders, has been hit by soaring energy bills.

“We’re having to find ways of having to decrease the money going out which is proving to be quite difficult… One thing we’re looking into at the moment is applying for grants or maybe doing some fundraising just to keep us above the water,” he said.

Fellow co-op member Sofia Cotrona, a student at the University of Edinburgh, said despite the co-op’s challenges, it provides an alternative for students who cannot afford private accommodation.

“I was in student halls (in first year) but I couldn’t afford that long-term because it’s definitely more expensive than the co-operative,” she said.

The co-op pays rent to a housing association which owns the building and is responsible for external maintenance.

Each member of the co-op has a specific role, which can include managing finances, maintenance and planning events.

Both Ms Cotrona and Mr Scott were hugely positive about the benefits of communal living.

Ms Cotrona, who comes from a small community in Italy, said when she first moved to Scotland she felt isolated.

“I was working while studying and most of the people around me didn’t seem like they were doing that,” she said.

“I remember applying because I thought that if I could have this little bubble of a community within a big city then maybe not everything was lost.

“I also think that I really like the idea of shaping a home that felt as such.”

Mr Scott became the co-op’s youngest member when he moved in several years ago, aged just 16, and said communal living has helped him build close friendships.

“By moving into the co-op you’re being a little bit more sustainable,” he said.

“You also become conscious of so many aspects of being sustainable, living as green as you can.”

Members can decorate their own rooms and renovate their flats, including laying new flooring, so long as sustainable materials are used.

“There is space to learn these things because I did the flooring and I had never used a mitre saw,” Ms Cotrona said.

“Now I know how to use it. I made my own loft bed and I’ve shown other people how to make loft beds.”

Ms Cotrona said living in the co-op is more than just about cheap rent.

“It requires a certain involvement and mindset,” she said.

“I wonder if Belfast can learn from us and find good balances between people who are involved and finding those people...”

Mr Scott said he wants more student co-ops to be set up across Edinburgh.

“If it was offered to us, we’d happily take a student accommodation building that has had no renovations done, still has the old furniture and we’d happily try and set something up as soon as possible,” he said.

“With the housing crisis and energy bills it would be snapped up.”

He added: “There’s not really any cons to living here. It’s such a great opportunity. If there are negative aspects they are greatly outweighed by the positives.”

By

By