THE UK joined the European Economic Community, as the EU was then called, in January 1973.

Fast-forward 47 years, with Brexit having taken place, and the UK is now formally out of the EU.

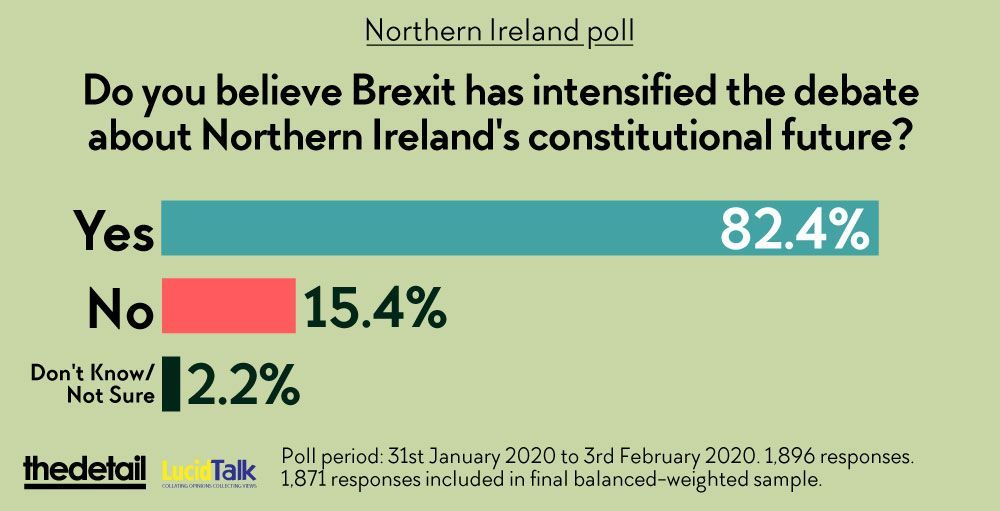

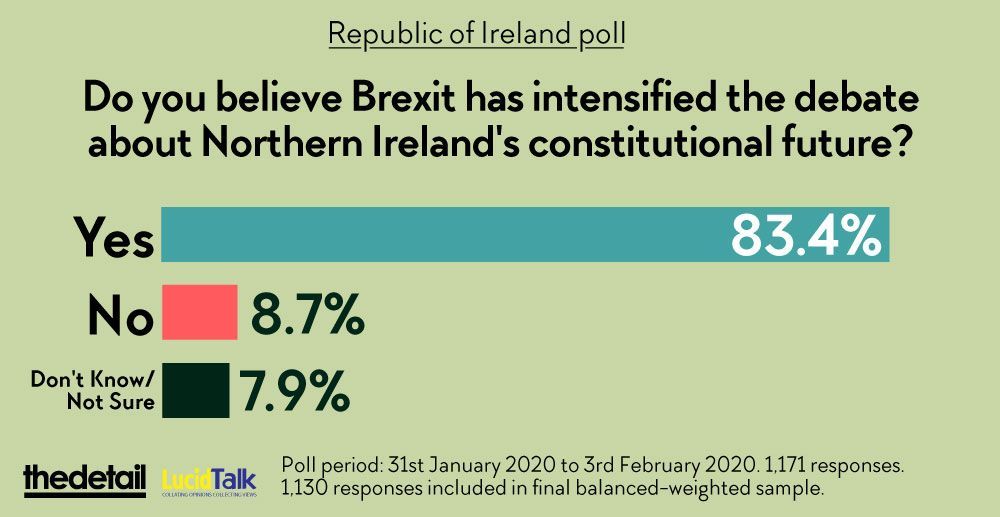

A LucidTalk poll, commissioned by The Detail, shows that 82.4% of people in NI believe Brexit has intensified the debate about the country's constitutional future. In ROI, it's 83.4%.

It’s the responsibility of the Secretary of State for Northern Ireland (SOSNI), now Brandon Lewis, to call a border poll, the outcome of which determines whether or not a united of Ireland becomes a reality.

If Mr Lewis triggers such a vote, it won't be the first in NI’s history.

Legislation was passed in December 1972 which provided the basis for a border poll to take place.

NI’s first, and to date only, border poll was then held three months later, on March 8, 1973, just two months after the UK initially joined in union with its European neighbours.

The deterioration of political stability in NI in the early 1970s had led to the willingness, of some, to hold the 1973 border poll.

It was the British Government’s hope that this would take the border out of politics and London’s, not Dublin’s, authority in NI would be rubber stamped by a pro-union result.

Northern Irish unionists felt similarly and supported the move. However, all the main anti-partition parties rejected the idea of a border poll on the basis that they felt the result was predetermined, given NI’s borders were drawn up in a way that protected unionism.

The nationalist parties, therefore, called for a boycott of the vote.

Between March 1972 and February 1973, in the build-up to the border poll, a total of 428 people were killed and 3,362 were injured in NI. The previous 11 months saw 234 killed and 2,713 injured.

In February 1973, 1,500 extra troops were sent to NI. In early March 1973, a further 1,000 were deployed, bringing the total garrison in the country to 17,500 troops.

A report about the 1973 poll – published by academics R.J Lawrence and S.Elliott, which was presented to Parliament by the then SOSNI, Merlyn Rees, in January 1975 – states it would have been almost impossible to 'conceive of more unfavourable conditions' in which to hold this vote.

Today, the report can be sourced in Queen's University Belfast's McClay Library.

The report also says that the issues at stake 'attracted virtually no public discussion, nor any marked degree of public attention until the week before the poll took place' and that public meetings, canvassing and loudspeaker tours, about its taking place, were 'noticeably absent'.

This report adds: 'Pro-union and anti-partition leaders knew that the prospect of changing each other's attitudes was remote and that the vast majority of voters had already made up their minds.'

In the end, 57.5% of the electorate voted for NI to remain in the UK with just 0.6% of those eligible voting in favour of reunifying with ROI. The nationalist boycott of the poll led to the other 41.9% of the electorate not voting.

Almost half a century later and a similar outcome in a prospective border poll is in no way plausible, for now it is those of a nationalist outlook who are pressing hardest for such a vote, while it’s unionist parties who fear it being called.

The Good Friday Agreement established that the Secretary of State can't make provisions for a referendum on Irish unity within seven years of a previous border poll.

There exists a fear within unionism that, ultimately, polls can be repeatedly held until nationalists get what they want and, once that happens, that there will be little chance of turning back the clock.

It can be said, with confidence, that the 1973 border poll did not take the border out of politics, as the British Government had hoped it would. In recent years, Brexit has had the opposite effect.

The protracted process of the UK leaving the EU has sharpened people’s minds on Ireland’s, and Scotland’s, constitutional futures. It has also polarised political discourse in Britain, between those who voted to leave the EU and those who wished to remain.

Discourse about NI's constitutional future is intense, but the climate of retributive violence – which provided the backdrop to the 1973 border poll – is incomparable to that which exists in the country today.

By

By